What to Look for in a Purchase Price Allocation

Executive Summary

Purchase price allocation is a critical step in the transaction reporting process under ASC 805. Future amortization expense, changes in the fair value of earnout liabilities, and even goodwill impairment testing all depend on the outcome of the initial allocation. This article will provide an overview of the PPA process, discuss common intangible assets, and review some best practices and potential pitfalls.

Introduction

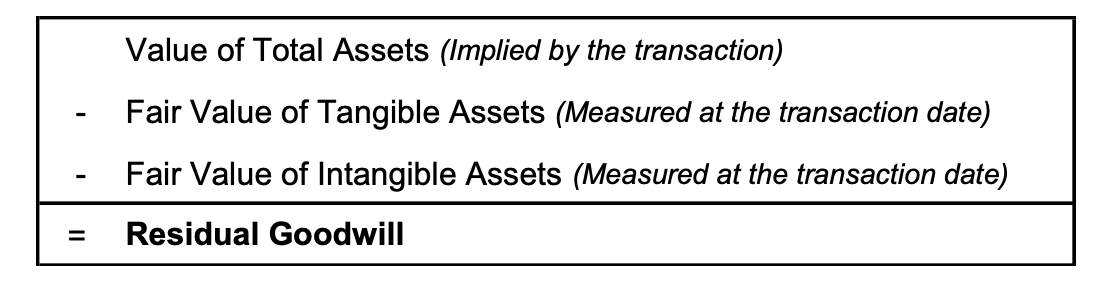

A purchase price allocation is just that—the purchase price paid for an acquired business is allocated among the acquired tangible and separately-identifiable intangible assets. The excess of the purchase price over these assets is residual goodwill. The following figure notes that the acquired assets are measured at fair value.

The initial allocation of transaction consideration among the various assets is important because certain assets are depreciated, others amortized, and other items (like contingent consideration) are remeasured at fair value in subsequent periods.

Deal Structure and Consideration

Transaction structures can vary from relatively straightforward asset purchases to more complex stock acquisitions. While the transaction structure itself would not dictate which intangible assets should be recognized, the structure of a deal (e.g., taxable vs. non-taxable) could influence the fair value of the assets acquired. Purchase agreements may include balance sheet adjustments, complex earnout provisions, and specific requirements that interact with other documents like buy-sell agreements. Understanding the industry characteristics of the acquired business can also provide valuable context to the identification and valuation of the intangible assets.

Deal consideration might include cash, notes, equity (rollover or otherwise), options, warrants, contingent consideration (or earnouts), and deferred consideration. Most of these forms of payment are self-explanatory, but we find that rollover equity and earnout consideration can be particularly nuanced, so we provide an overview below.

Equity Consideration

In the context of a business combination, equity consideration typically refers to rollover equity, which is equity in the newly combined business. In some industries, rollover equity has become more popular as a component of deal consideration. The benefits of rollover equity, from the acquirer’s perspective, are twofold: 1) rollover equity helps align the interests of the sellers with the acquirer’s business, and 2) rollover equity, like contingent consideration, offers downside protection compared to cash consideration. Advantages of rollover equity from the acquiree’s perspective include the satisfaction of continued ownership in the operations they manage and the opportunity to increase the value of their stock holdings alongside the acquirer. After all, converting from “owner” to “employee” may feel like a demotion to some, even when accompanied by a multimillion-dollar payout.

Equity consideration may also include replacement of the acquiree’s share-based payment awards with those of the acquirer. Depending on the exact nature of each party’s share award contracts, this item may impact the value of the consideration.

Contingent Consideration & Earnouts

We often see earnouts structured into a deal as a mechanism for bridging the gap between the price the acquirer wants to pay and the price the seller wants to receive. Earnout payments can be based on revenue growth, earnings growth, employee retention, customer retention, or any other metric agreed upon by the parties. Structuring a portion of the total purchase consideration as an earnout provides some downside protection for the acquirer while rewarding the seller for meeting or exceeding growth expectations. Earnout arrangements represent a contingent liability for the acquirer that must be recorded at fair value on the acquisition date. Depending on the term of the earnout and the reporting requirements of the acquirer, the earnout liability may need to be remeasured quarterly or annually, with changes in the liability flowing through the income statement. When these liability changes are significant, they can introduce added volatility to an acquirer’s earnings.

Common Intangible Assets

The AICPA’s recently issued draft Accounting and Valuation Guide on Business Combinations provides guidance on the valuation of intangible assets. A overview of some of the more common intangible assets is provided below.

Customer-Related Intangible Assets

Customer-related intangible assets (“CRIAs”) may include, for example, customer lists, order or production backlog, customer contracts and related customer relationships, noncontractual customer relationships, and customer loyalty programs.

In our experience, the most common CRIA is customer relationships, whether contractual or noncontractual. Generally, the value of existing customer relationships is based on the revenue and profitability expected to be generated by existing accounts, factoring in an expectation of annual account attrition. Attrition is often estimated using historical client data, prospective characteristics, or industry churn/attrition rates.

Tradename

Tradenames (or trademarks) are words, names, symbols, or other devices used in trade to indicate the source of a product and to distinguish it from the products of others. The fair value of a tradename in a business combination should reflect the perspective and expected use of the name by a market participant, not necessarily the subject acquirer. Some acquirers might expect to use the acquired firm’s name into perpetuity or only use it during a transition period, as the acquired firm’s services are brought under the acquirer’s name. This decision can depend on many factors, including the acquired firm’s reputation within a specific market, the acquirer’s desire to bring its services under a single name, and the ease of transitioning the acquired company’s existing client base.

Generally, tradename value can be derived with reference to the hypothetical royalty costs avoided through ownership of the name. A royalty rate is often estimated through analysis of comparable transactions and an analysis of the characteristics of the individual firm’s name. The present value of cost savings achieved by owning rather than licensing the name over the future use period provides a measure of the tradename value.

Noncompetition agreements

In many firms, especially services firms, a few top executives or managers may account for a large portion of new client generation. Deals involving such firms will typically include non-competition and non-solicitation agreements that limit the potential damage to the company’s client and employee bases if such individuals were to leave.

These agreements often prohibit the covered individuals from soliciting business from existing clients or recruiting current company employees. In the agreements we’ve observed, a restricted period of two to five years is common. In certain situations, the agreement may also restrict the individuals from starting or working for a competing firm within the same market. The value attributed to a non-competition agreement is derived from the expected impact of competition from the covered individuals on the firm’s cash flow and the likelihood of those individuals competing in the absence of an agreement. Factors driving the likelihood of competition include the age of the covered individual and whether or not the covered individual has other incentives not to compete aside from the legal agreement. For example, if the individual is a beneficiary of an earnout agreement or received equity in the acquirer as part of the deal, the probability of competition may be significantly lessened.

Recently, the FTC has moved to place restrictions on non-competition agreements and, in most cases, disallow them. However, non-competition agreements arising in connection with a transaction would most likely still be enforceable and, thus, hold value.

Technology (Patented and Unpatented)

Technology-based intangible assets may include software, databases, license agreements, patents, know-how, or trade secrets. To be allocated value, technology assets must generally be separable, documentable, transferable, or otherwise distinguishable from other acquired assets.

Technology assets are typically allocated value based on the cash flow or revenue stream the asset is expected to generate over its useful life. The fair value of a technology-based asset would consider the existing functionality of the technology, anticipated market demand, and functional/economic obsolescence of the existing technology.

In-Process Research and Development Assets (IPR&D)

Intangible assets used in research and development activities acquired in a business combination are initially recognized at fair value and classified as indefinite lived assets until completion or abandonment. IPR&D is typically valued using the income approach. In certain circumstances, the cost approach may be applied instead, depending on the stage of development. In subsequent periods, an IPR&D asset would be subject to periodic impairment testing. Upon completion or abandonment of the R&D efforts, the acquirer would reassess the useful life of the indefinite lived intangible asset.

Operating Rights

Operating rights are legal rights necessary to operate a business. Key characteristics of operating rights include regulations governing access, use, and transfer of the asset, as well as scarcity of the asset. Operating rights include commercial franchise agreements, government-granted broadcast licenses or taxi medallions, and government-granted monopoly rights. Operating rights are typically valued using the income approach. In certain industries, operating rights may comprise a significant portion of the fair value in a purchase price allocation because of the legal necessity to possess such rights in order to operate the subject business, as well as their limited availability.

Assembled workforce

In general, the value of the assembled workforce is a function of the avoided hiring and assembly costs associated with finding and training new talent. An existing employee base with market knowledge, strong client relationships, and an existing network may suggest a higher value allocation to the assembled workforce. Unlike the other intangible assets previously discussed, the assembled workforce value is not recognized or reported separately, but instead is included as an element of goodwill under GAAP. The value of an assembled workforce is commonly valued as a supporting (or contributory) asset to other, more pivotal, intangible assets in a transaction (such as customer relationships or technology).

Goodwill

Goodwill arises in a transaction as the difference between the price paid for a company and the value of its identifiable assets (tangible and intangible). Expectations of synergies, strategic market location, and access to a particular industry niche are common examples of the factors that contribute to residual goodwill value. Generally speaking, the higher the price paid in a transaction (relative to other bidders or the prevailing “market” price in the industry), the more goodwill will be recorded.

Allocation to goodwill is ultimately calculated based on the unique factors pertaining to each transaction. Goodwill allocation trends may vary both between and within industries. For example, Mercer Capital’s Energy Team’s 2023 Energy PPA Study found that the percentage of consideration allocated to goodwill varied between oilfield services companies and midstream companies.

Goodwill must be tested for impairment under certain circumstances, such as changes in the macroeconomic environment or in firm-specific metrics. The accounting guidance in ASC 350 prescribes that interim goodwill impairment tests may be necessary in the case of certain “triggering” events. For public companies, perhaps the most easily observable triggering event is a decline in stock price, but other factors may constitute a triggering event. Further, these factors apply to both public and private companies, even those private companies that have previously elected to amortize goodwill under ASU 2017-04.

Potential Pitfalls and Best Practices for PPAs

What are some of the pitfalls in purchase price allocations?

Sometimes differences arise between expectations or estimates prior to the transaction and fair value measurements performed after the transaction. An example is contingent consideration arrangements. Estimates from the deal team’s calculations could vary from the fair value of the corresponding liability measured and reported for GAAP purposes. This could create misunderstandings at the management or board level about the anticipated payments or the magnitude of future payment exposure.

Similarly, to the extent that amortization estimates are prepared prior to the transaction, any variance in the allocation of total transaction value to amortizable intangible assets and non-amortized, indefinite lived assets – be they identifiable intangible assets or goodwill – could also lead to different future EPS estimates for the acquirer.

How can I learn what intangible assets are commonly recognized in my industry?

At Mercer Capital, we have prepared hundreds of purchase price allocations across numerous industries. We discuss these types of questions frequently with prospective and current clients. One common method of answering this question is to review public filings of companies in your industry to review their purchase price disclosures. Many companies will disclose the types of intangible assets acquired, their relative values, and useful life estimates for various assets. These types of disclosures can be very helpful when planning for a purchase price allocation.

What are the benefits of looking at the allocation process early?

The opportunity to think through and talk about some of the unusual elements of the more involved transactions can be enormously helpful. We view the dialogue we have with clients when we prepare a preliminary PPA estimate prior to closing as a particularly important part of the project. It can also be helpful to hold a preliminary call with the valuation team and the external auditor to discuss the potential intangible assets in the deal, the anticipated valuation methods/approaches, and any unique circumstances. This deliberative process results in a more robust analysis that is easier for the external auditors to review, and thus better stands the test of time, requiring fewer true-ups or other adjustments in the future.

While ASC 805 permits companies up to one year to finalize and true-up the allocation, the time to begin estimating the accounting and financial impact from the intangible asset allocation is before a deal closes, not the week before the audit or quarterly filing is due.

Conclusion

The proper identification and allocation of value to intangible assets and the calculation of those asset fair values require both valuation expertise and knowledge of the subject industry. Mercer Capital brings these together with decades of experience in financial reporting matters across nearly every major industry. If your company has recently completed a transaction or is contemplating its next acquisition, call one of our professionals to discuss your valuation needs in confidence.

>> Download a PDF of the article