Understand the Income Approach in a Business Valuation

What Is the Income Approach and How Is It Utilized?

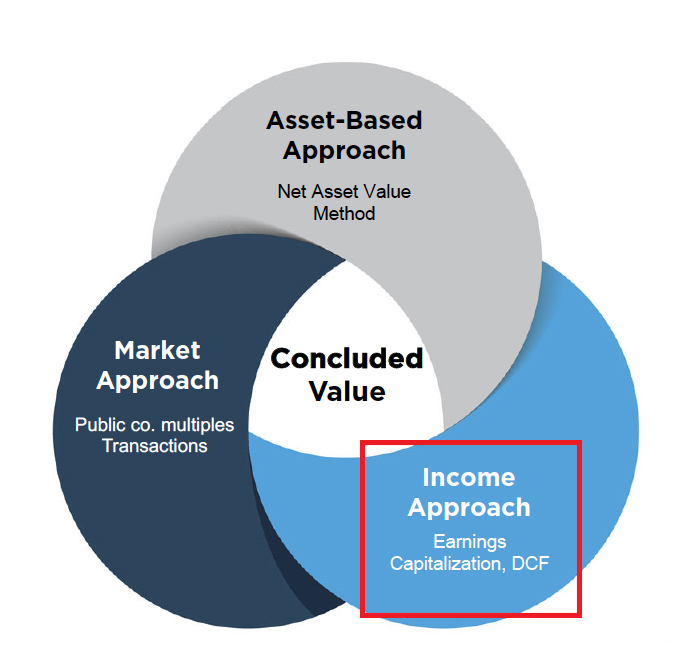

We recently wrote about the market approach, which is one of the three primary approaches utilized in business valuations. In this article, we’ll be presenting a broad overview of the income approach. The final approach, the asset-based approach, will discussed in a future article. While each approach should be considered, the approach(es) ultimately relied upon will depend on the unique facts and circumstances of each situation.

The income approach is a general way of determining the value of a business by converting anticipated economic benefits into a present single amount. Simply put, the value of a business is directly related to the present value of all future cash flows that the business is reasonably expected to produce. The income approach requires estimates of future cash flows and an appropriate rate at which to discount those future cash flows.

Methods under the income approach are varied but typically fall into one of two categories:

- Single period methods, for example capitalization of earnings or free cash flow

- Multi-period methods like the discounted cash flow (DCF)

The question if often asked, which method should you use, or should you use multiple methods? Also, does one use single period methods, or multi-period method? It depends on the facts and circumstances, including but not limited to, whether the business is in a mature or growing business cycle, if budgets/projections are prepared in normal course of business, among other considerations. More importantly, the analyst must evaluate if trends analyzed from the business’ historical performance provide a reasonable indication of the future, and which methodology or methodologies best capture that future economic stream of benefits.

Normalizing Adjustments

Before analyzing each method, it is important to start with normalizing adjustments, which serve as a foundation for both income approach methodologies. Normalizing adjustments adjust the income statement of a private company to show the financial results from normal operations of the business and reveal a “public equivalent” income stream. In creating a public equivalent for a private company, another name given to the marketable minority level of value is “as if freely traded,” which emphasizes that earnings are being normalized to where they would be as if the company were public, hence supporting the need to carefully consider and apply, when necessary, normalizing adjustments. There are two categories of adjustments.

Non-Recurring, Unusual Items

Mercer Capital dives deep into this subject in this article, but here are some highlights. These adjustments eliminate one-time gains or losses, unusual items, non-recurring business elements, income/expenses of non-operating assets, and the like. Examples include, but are not limited to:

- One-time legal settlement. The income (or loss) from a non-recurring legal settlement would be eliminated and earnings would be reduced (or increased) by that amount.

- Gain from sale of asset. If an asset that is no longer contributing to the normal operations of a business is sold, that gain would be eliminated and earnings reduced.

- Life insurance proceeds. If life insurance proceeds were paid out, the proceeds would be eliminated as they do not recur, and thus, earnings are reduced. The balance sheet impact can be dependent on whether the company has a direct obligation to repurchase the shares or not.

- Restructuring costs. Sometimes companies must restructure operations or certain departments, the costs are one-time or rare, and once eliminated, earnings would increase by that amount.

Discretionary Items

These adjustments relate to discretionary expenses paid to or on behalf of owners of private businesses. Examples include the normalization of owner/officer compensation to comparable market rates, as well as elimination of certain discretionary expenses, such as expenses for non-business purpose items (lavish automobiles, boats, planes, personal living expenses, etc.) that would not exist in a publicly traded company.

For more, refer to our article “Normalizing Adjustments to the Income Statements” and Chris Mercer’s blog.

Single Period Capitalization Method

Once the analyst determines adjusted earnings, we can move forward to capitalizing these economic benefits.

The simplest method used under the income approach is a single period capitalization model. Ultimately, this method is an algebraic simplification of its more detailed DCF counterpart. As opposed to a detailed projection of future cash flow, a base level of annual net cash flow and a sustainable growth rate are determined.

The value of any operating asset/investment is equal to the present value of its expected future economic benefit stream.

If the growth in cash flows is constant, this can be simplified:

Where

CF = Next year’s cash flow

g = perpetual growth rate

r = discount rate for projected cash flows

The denominator of the expression on the right (r – g) is referred to as the “capitalization rate,” and its reciprocal is the familiar “multiple” that is applicable to next year’s cash flow. The multiple (and thus the firm’s value) is negatively correlated to risk and positively correlated to expected growth. There are two primary methods for determining an appropriate capitalization rate—a public guideline company analysis or a “build-up” analysis (previous article by Mercer Capital where we discussed the discount rate in detail).

Discounted Cash Flow Method

Businesses may be valued using the DCF method because this method allows for modeling of varying or near-term accelerated growth revenues, expenses, and other sources and uses of cash over a discrete projection period. Beyond the discrete projection period, it is assumed that the business will grow at a constant rate into perpetuity. As that point, the future beyond the projection period is capitalized as the terminal value and the method converges to the single period capitalization.

In circumstances where no changes in the business model or capital structure are expected, a single period capitalization method may be sufficient. Ultimately, the DCF’s output is only as good as its inputs, therefore, testing of assumptions and reasonableness is critical.

The discounted cash flow methodology requires assumptions, but the formula can be broken down to three basic elements:

- Projected future cash flows

- Discount rate

- Terminal value

Projected Future Cash Flows

Discrete cash flows are forecasted for as many periods as necessary until a stabilized earnings stream could be anticipated (commonly in the range of 3-10 years). Ideally, projections will be sourced from management, but if management projections are not available, a competent valuation professional may choose to develop a forecast based on historical performance, industry data, and discussions with management. It is important to test the reasonableness of the projections by comparing historical and projected performance as well as expectations based on the subject company’s history and the industry in which it operates.

Discount Rate

A discount rate is used to convert future cash flows to present value as of the valuation date. Factors to consider include, but are not limited to business risk, supplier and/or customer concentrations, market and industry risk, size of the company, financial leverage, capital structure, among others. For a detailed look into discount rates, see a recent article published by Mercer Capital.

Terminal Value

The terminal value captures the value of the company into perpetuity. It uses a terminal growth rate, the discount rate, and the final year cash flow to arrive at a value, which is discounted and added to the discrete cash flow projections.

Conclusion

The income approach can determine the value of an operating business using financial metrics, growth rate and discount rate unique to the subject company. However, each method within the income approach must be selected based on applicability and facts and circumstances unique to the matter at hand; thus, a competent valuation expert is needed to ensure that the methods are applied in a thoughtful and appropriate manner.