Valuation Lessons from Credit Union & Bank Transactions

In recent years, credit unions have been increasingly active as acquirers in whole bank and branch transactions. This session focuses on the top considerations for credit unions when assessing and valuing bank and branch franchises in the current environment.

For bankers, this session should enhance your knowledge regarding how credit unions identify potential targets, assess potential opportunities and risks of a bank or branch acquisition, and ultimately determine a valuation range for target banks and branches.

This session, presented as part of the 2021 Acquire or Be Acquired Conference sponsored by Bank Director, addresses these issues.

Understand the Discount Rate Used in a Business Valuation

What Comprises the Discount Rate and What’s a Reasonable Range?

The discount rate is the key factor in business valuation that converts future dollars into present value as of the valuation date. For a layperson, the discount rate utilized in a business valuation may appear to be subjective and pulled out of a hat. However, the discount rate is a crucial component of the valuation formula and must be assessed for the specific company at hand.

Using any method under the income approach, the valuation formula comes down to three things:

- Ongoing (or expected) cash flow (or other measure of earnings)

- Discount rate

- Growth rate

In valuations that “feel” too high or too low, one of the potential culprits may be an aggressive discount rate, either on the high or low end. There are several generally accepted methodologies to build up discount rates employed by valuation analysts. In this article, we will examine the various components of a discount rate. Then, we will relate the discount rate to rates of return of other investments that should provide a commonsense road map for what is reasonable and what is not.

What Is a Discount Rate?

Companies with larger cash flows are likely to be more valuable, as are those with cash flows that are growing at a faster rate. Each of these statements makes perfect sense. Now, if the future cash flows are less certain, they are deemed to be riskier, which reduces the value of the business. The discount rate “discounts” future cash flows to a present value. As we have all heard, “a dollar today is better than a dollar tomorrow.” Measuring the present value of future earnings allows us to develop a value for a business today.

The discount rate goes by many names including “equity discount rate,” “return on investment,” “cost of capital,” and “rate of return.” For companies that use debt, the appropriate way to discount cashflows may be the weighted average cost of capital, or “WACC.” Thinking about a discount rate as a rate of return is likely the most intuitive approach.

Returns to an equity investor come after all other parties have been paid. Debt capital providers are paid before equity capital providers, typically at a fixed or floating interest rate (for example, a company’s line of credit could be 4.0% fixed rate or vary, such as 1% over the prime rate). After generating revenue, paying expenses and taxes, and reinvesting funds needed in the business, any remaining cash flow is shared by the equity investors. Because equity investors come last, they require the highest rate of return in order to provide equity capital to a business. Intuitively, this explains why the cost of equity, or “discount rate,” is higher than the cost of debt, or interest rate.

How to Build Up a Discount Rate

Before we delve into what is reasonable and what is not, one must first understand the components of a discount rate as these help the attorney understand how an appraiser estimates this rate. We describe the development of an equity discount rate with a description of each component below.

Risk-Free Rate: As alluded to previously, we would all prefer a dollar today over a dollar tomorrow, which both removes the uncertainty of receipt and quells any potential concerns about lost purchasing power from rising prices. To build up the discount rate, we begin with a base rate called the “risk-free rate,” which compensates for the time value of money. An example of a risk-free rate is the 20-Year Treasury Bond yield as of the valuation date. If an appraisal uses an alternative figure that is materially different than the prevailing rate, the assumption would likely require justification.

Equity Risk Premium: Next, to capture generic market risk for the equity market, appraisers employ an “equity risk premium,” frequently in the range of 4.0% to 7.0%, which captures what an investor would expect for an investment in the equity market over a less risky investment like the bond market. Again, something out of this range would likely require justification. [1]

Beta: The equity risk premium is then multiplied by a selected beta. The beta statistic measures a company’s exposure to market risks, with a beta of 1.0 indicating typical market risk. Low beta companies or industries are less correlated with market risk, while high beta companies are more exposed to market risk. For example: auto dealers and airlines tend to ebb and flow with the economy, doing well when the market is good and declining when economic activity contracts, meaning they tend to have betas of 1.0 or higher. In contrast, grocery stores tend to have a beta below 1.0. When the economy contracts, consumers increase their consumption at grocery stores instead of restaurants to save money. Consumers also need toilet paper regardless of the economic environment, and companies that sell such durable goods (like grocery stores) tend to be lower beta companies.

To this point, we have built up the equity discount rate under the Capital Asset Pricing Model (“CAPM”) for a diversified equity market investment.[2] The risk-free rate plus the equity risk premium (assuming a beta of 1.0) gives a rate of return of approximately 7.0% to 8.0%. This should sound familiar because money managers and retirement planners frequently say equity investors should anticipate investment returns on the order of 7.0%, or something in this range. While Mercer Capital makes no such investment advice, this is a reasonable consideration for large, diversified equity portfolios in the context of building up a discount rate for a smaller private company. However, in recognition of the greater risks inherent in privately held smaller companies, business valuation analysts frequently consider two other sources of risk premia: size and specific company.

Size Premium: Smaller companies tend to be subject to greater issues with concentration and diversification. Smaller companies also tend to have less access to capital, which tends to raise the cost of capital. To compensate for the higher level of risks as compared to the broad larger equity market, appraisers frequently add a premium of approximately 3.0% to 5.0% (or more, for very small businesses) to the discount rate when valuing smaller companies. To get an idea of reasonableness, we can consider the following example. A company valued at over $200 million may seem large, but it is actually relatively small when compared to most publicly traded companies. As such, a size premium would still apply, albeit on the lower end. Valuation analysts source these size premiums from data which provides empirical evidence in support of risks associated with smaller size. This data is updated annually, and providers such as Duff & Phelps are frequently cited.

Specific Company Risk Premium: The final component of a discount rate is the specific company risk premium. This represents the “risk profile” specific to the individual subject company above and beyond the factors above – i.e., what is the required return an investor requires to invest in said company over any other investment?

To illustrate with an example, a soon-to-retire CEO of a small business maintains all client relationships. In assessing the potential risk(s) to the business, we would inquire about and assess the risk of clients leaving when the CEO retires. In addition to the risk of losing clients, there are other risks associated with the departure of a key executive. Valuation analysts refer to these risks as “key person risk,” or “key person dependency.” We would also assess depth of other management and succession planning. A few additional examples, but certainly not all, of company specific risk are shown below:

-

- Customer/Supplier Concentration: If the ongoing level of earnings/cash flow is heavily dependent on one key customer/vendor, and the loss of said customer/supplier would lead to significant revenue loss, a risk premium is appropriate.

- Product Diversification: Does the company reap sales from a one hit wonder product, or are other product offerings available that diversify this risk?

- Product Evolution/Research & Development: Is there research & development to keep the products evolving with consumer demands and technological advancements?

- Geographic Concentration: If a company solely operates in one city or geographic region, the company could suffer if the local economy lags the growth of the national economy. Having operations in multiple locales would help reduce this risk. Also, concentration may create a ceiling to potential growth and expansion.

- Earnings Volatility: Do earnings change significantly from year to year? If so, an investor in such a company would likely require a higher return to compensate for the uncertainty. (Note: it is important that the valuation analyst is cautious and does not double count risk considering the selected earnings stream. For example, if a company has one down year but the analyst includes it in a historical average, it may not be appropriate to add additional risk for earnings volatility. In this case, the risk may already be captured in giving weight to it in the analysis of ongoing earnings.)

- Competitive Environment: Are there many competitors, and how does the company perform in comparison to those competitors? Does the company offer goods or services which are differentiated?

When determining a specific company risk premium, some analysts may choose to assess a company through a SWOT analysis – strengths, weakness, opportunities, and threats of the company – relative to past performance, performance of its peers, the industry, and the broader economy. Put simply, what is the risk profile of the business? If there are risks (or lack thereof) that are specific to said company, how much higher or lower does the discount rate have to be for an investor to be willing to invest in this company instead of an alternative company or investment?

The specific company risk premium is frequently an area where experts may differ due to selection of varying levels of risk for a company. While understanding what “feels” reasonable here takes nuance and experience, a valuation analyst should provide the attributes which support the selected risk premium.

What Is a Reasonable Discount Rate and What’s in Range?

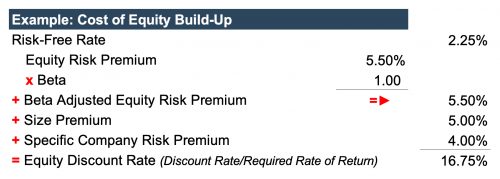

Following our equity build-up example in Figure 1, adding a size premium of 5.0%, and specific company of 4.0% to an equity market return of 7.75% leads to a discount rate of 16.75%. For a smaller, riskier company, this could be higher; however, for a larger, less risky company with consistent history of strong earnings, this could be lower. An equity discount rate range of 12% to 20%, give or take, is likely to be considered reasonable in a business valuation. This is about in line with the long-term anticipated returns quoted to private equity investors, which makes sense, because a business valuation is an equity interest in a privately held company. Again, while many of the specific terms utilized in the build-up of a discount rate may be new to attorneys, rates of return quoted in that context are more familiar to many.

A business appraisal with a discount rate below 10% likely deserves more scrutiny, but it may be reasonable if the company is sufficiently large, diversified, well-capitalized, less exposed to market risk, has a strong management team and succession plan, and generates consistent cash flow and/or growth.

On the other end of the spectrum, a company with a discount rate in excess of 25% may be undervalued, and such a discount rate similarly deserves justification. However, there could be numerous reasons why this is ultimately reasonable given specific facts and circumstances. Early stage/start-up companies without sufficient history of earnings and performance would likely have a high discount rate. While there could be certain instances where a discount rate above 25% may be reasonable, a proper appraisal will enumerate in detail why such a large discount rate is warranted.

Conclusion

In financial situations that may be scrutinized by courts and other potential adversaries, an expert’s financial, economic, and accounting experience and skills are invaluable. These complex analyses are best performed by a competent financial expert who will be able to define and quantify the financial aspects of a case and effectively communicate the conclusion.

[1] Mercer Capital regularly reviews a spectrum of studies on the equity risk premium and also conducts its own study. Most of these studies suggest that the appropriate large capitalization equity risk premium lies in the range of 4.0% to 7.0%.

[2] W.F. Sharpe, “Capital Asset Prices: A Theory of Market Equilibrium Under Conditions of Risk,” Journal of Finance, Vol. 19 (1964): pp. 425-442.

Should You Diversify Your Family Business?

Travis W. Harms, CFA, CPA/ABV, presented the session “Should You Diversify Your Family Business” at Transitions Spring Conference 2021 on March 24, 2021. This conference was sponsored by Family Business Magazine.

Diversification — such as entry into new lines of business, new geographies, or new markets — can protect your family enterprise from economic downturns. In this presentation, he provides an overview of what is involved in diversifying a family business and the best way to calculate whether it’s the right move for the business.

What Attorneys Should Know About Valuations of Closely Held Businesses

Karolina Calhoun, CPA/ABV/CFF, presented the session “What Attorneys Should Know About Valuations of Closely Held Businesses” at the Tennessee Trial Lawyers Association’s “Memphis Family Law Seminar 2021” on March 18, 2021.

The valuation of a business is a complex process, requiring specialized professionals who apply the same finance & economic fundamentals used by public companies to evaluate and price private companies. This presentation delves into the processes and methodologies used in a valuation and provides examples of scenarios that may invoke the need for valuation services.

Mortgage Banking Lagniappe

2020 was a tough year for most of us. Schools and churches closed, sports were cancelled, and many lost their jobs. There were a select few, however, that thrived during 2020. Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk saw a meteoric rise in their personal net worth over the past 12 months. Mortgage bankers are another group showered with unexpected riches last year (and apparently this year).

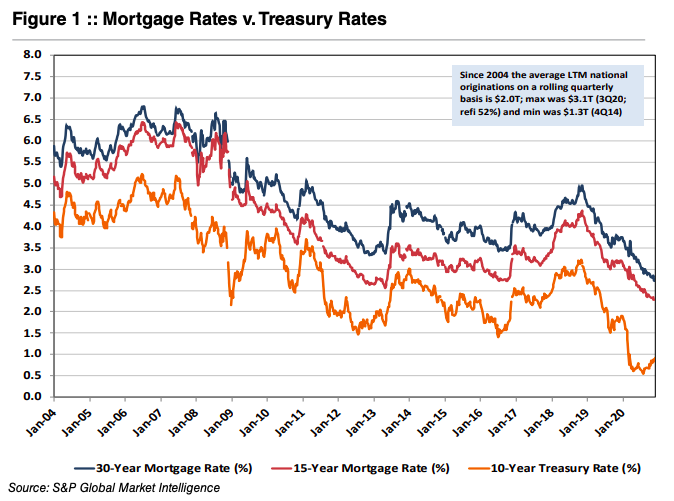

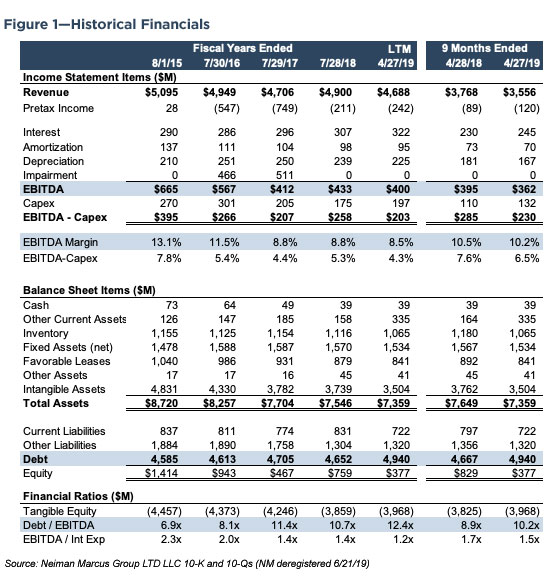

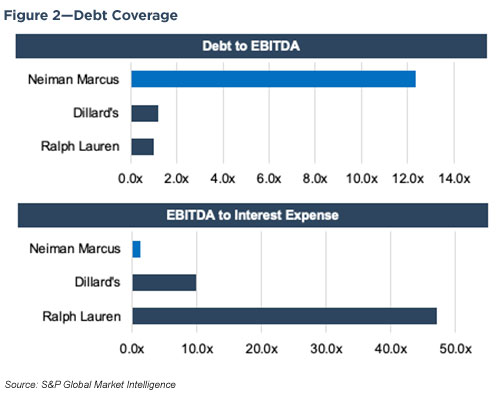

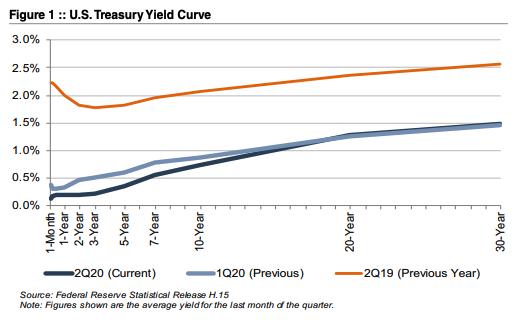

As shown in Figure 1, long-term U.S. Treasury and mortgage rates have been in a long-term secular decline for about four decades. Last year, long-term rates fell to all-time lows because of the COVID induced recession after having declined modestly in 2019 following too much Fed tightening in 2018. The surprise was not an uptick in refinancing activity, but that it was accompanied by a strong purchase market too. Housing was and still is hot; maybe too hot.

Overlaid on the record volume (the Mortgage Bankers of America estimates $3.6 trillion of mortgages were originated in 2020 compared to $2.3 trillion in 2019 and $1.7 trillion in 2017 and 2018) was historically high gain on sale (“GOS”) margins. The industry was capacity constrained after cutting staff in 2018 when rates were then rising.

Private equity and other owners of mortgage companies set their eyes on the public markets after many companies attempted to sell in 2018 with mixed success at best. During the second half of 2020, Rocket Mortgage ($RKT) and Guild Mortgage ($GHLD) made an initial public offering and began trading while seven other nonbank mortgage companies have either filed for an IPO or announced plans to do so. Also, United Wholesale Mortgage ($UWMC) went public by merging with a SPAC.

The inability of several (or more) mortgage companies to undergo an IPO at a price that was acceptable to the sellers has an important message. The industry was accorded a low valuation by Wall Street on presumably peak earnings even though many mortgage companies will produce an ROE that easily exceeds 30%. The assumption is that earnings will decline because rates will rise and/or more capacity will reduce GOS margins.

While it is likely 2020 will represent a cyclical peak, no one knows how steep (or gentle) the descent will be and how deep the trough will be. Mortgage companies may produce 20% or better ROEs for several years. One may question the multiple to place on 2020 earnings, but book value could double in three or four years if conditions remain reasonably favorable.

Community and regional banks with mortgage operations have benefitted from the mortgage boom, too. Although various bank indices were negative for the year, it could have been much worse given investor fears surrounding credit losses and permanent impairment to net interest margins given the collapse in rates. In a sense, outsized mortgage banking revenues funded reserve builds for many banks and masked revenue weakness attributable to falling NIMs.

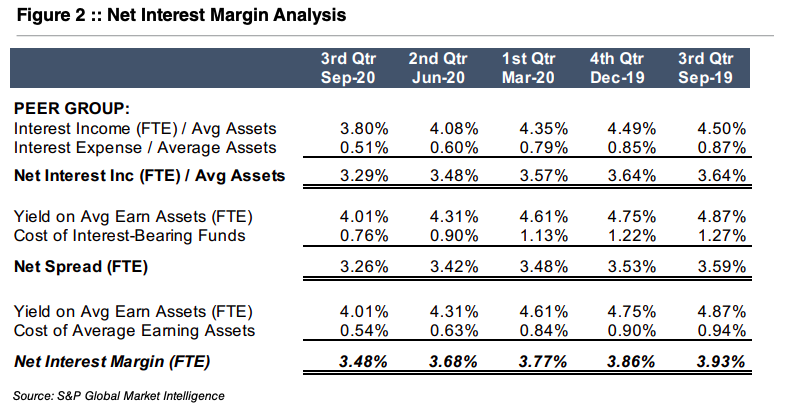

The average NIM for banks in the U.S. with assets between $300 million and $1 billion as of September 30, 2020 is shown in Figure 2. The NIM fell 45bps from 3Q19 to 3Q20 due to multiple moving pieces but primarily reflected an increase in liquid assets because deposits flooded into the banking system and because the reduction in the yield on loans and securities was greater than the reduction in the cost of funds.

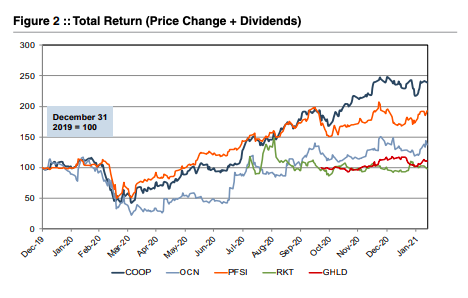

Unless the Fed is able (and willing) to raise short-term policy rates in the next year or two, we suspect loan yields will grind lower as lenders compete heavily for assets with a coupon (i.e., loans) because liquidity yields nothing and bonds yield very little. Deposit costs will not offset because rates are or soon will be near a floor. Fee income and expense management are more critical than ever for banks to maintain acceptable profitability. When analyzing the same group of banks (assets $300M – $1B), banks with higher GOS revenues as a percentage of total revenue tended to be more profitable. As shown in Figure 3, median profitability was ~15% greater in the trailing twelve months for banks more engaged in mortgage activity than those that were not.

Selling long-term fixed-rate mortgages for most banks is a given because the duration of the asset is too long, especially when rates are low. The decision is more nuanced for 15-year mortgages with an average life of perhaps 6-7 years. With loan demand weak and banks extremely liquid, most banks will retain all ARM production and perhaps some 15-year paper as an alternative to investing in MBS because yields on originated paper are much better.

As for 30-year mortgages, net production profits for 3Q20 increased above 200bps according to the MBA for the first time since the MBA began tracking the data in 2008. Originating and selling long-term fixed rate mortgages has been exceptionally profitable in 2020.

Mortgage banking in the form of originations is a highly cyclical business (vs servicing); however, it is a counter-cyclical business that tends to do well when the economy is struggling and therefore core bank profitability is under pressure. We have long been observers of the mortgage banking conundrum of “what is the earnings multiple?” It is a tougher question for an independent mortgage company compared to a bank where the earnings are part of a larger organization. Even when outsized mortgage banking earnings may weigh on a bank’s overall P/E, mortgage earnings can be highly accretive to capital.

In the February issue of Bank Watch, we will explore how to value a mortgage company either as a stand-alone or as a subsidiary or part of a bank to understand in more detail the true valuation impacts of mortgage revenue.

Originally appeared in Mercer Capital’s Bank Watch, January 2021.

Mortgage Banking Lagniappe (Part II)

The January Bank Watch provided an overview of the mortgage industry and its importance in boosting bank earnings in the current low-rate environment. As we discussed, mortgage volume is inversely correlated to interest rates and more volatile than net interest income. In this article, we discuss key considerations in valuing a mortgage company/subsidiary, including how the public markets price them.

Valuation Approaches

Similar to typical bank valuations, there are three approaches to consider when determining the value of a mortgage company/subsidiary: the asset approach, the market approach, and the income approach. However, since the composition of both the balance sheet and income statement differ from banks, several nuances arise.

Asset Approach

Asset based valuation methods include those methods that write up (or down) or otherwise adjust the various tangible and/or intangible assets of an enterprise. For a mortgage company, these assets may include mortgage servicing rights (“MSR”). The fair value of the MSR book is the net present value of servicing revenue minus related expenses, giving consideration to prepayment speeds, float, and servicing advances. MSR fair value tends to move opposite to origination volume. For example, MSR values tend to increase in periods marked by low origination activity. Other key items to consider include any non-MSR intangible assets, proprietary technology, funding, relationships with originators and referral sources, and the existence of any excess equity.

Market Approach Market

methods include a variety of methods that compare the subject with transactions involving similar investments, including publicly traded guideline companies and sales involving controlling interests in public or private guideline companies. Historically, publicly traded pure-play mortgage companies were a rare breed; however, the COVID-19 mortgage boom has produced several IPOs, and others may follow. There are many publicly traded banks that derive significant revenues from mortgage operations, especially in this low-rate environment.

The basic method utilized under the market approach is the guideline public company or guideline transactions method. The most commonly used version of the guideline company method develops a price/earnings (P/E) ratio with which to capitalize net income. If the public company group is sufficiently homogeneous with respect to the companies selected and their financial performance, an average or median P/E ratio may be calculated as representative of the group. Other activity-based valuation metrics for the mortgage industry include EBITDA, revenues, or originations.

Another relevant indicator includes price/tangible book value as investors tend to treat tangible book value as a proxy for the institution’s earnings capabilities. The key to this method lies in finding comparable companies with a similar revenue mix (high fee income) and profitability.

When examining the public markets, there are generally two types of companies that can be useful in gathering financial and valuation data: banks emphasizing mortgage activities and non-bank mortgage companies.

Group 1: Banks with Mortgage Revenue Emphasis

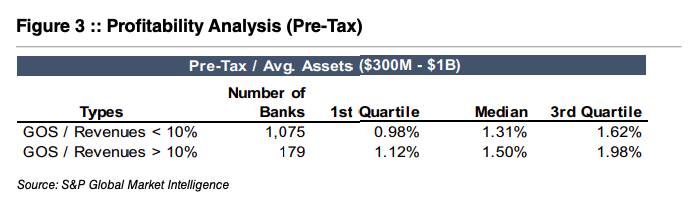

Figure 1 details the first step in identifying a group of banks with significant mortgage operations. First, financial data from the most recently available quarter (4Q20) regarding banks with assets between $1 billion and $20 billion were identified. Once that broad group of banks is identified, it is then important to segment the group further to identify those with significant gain on loan sales as a proportion of revenue and particularly those with higher than typical mortgage revenues/originations as opposed to SBA or PPP loan originations.

Group 2: Non-Bank Mortgage Companies

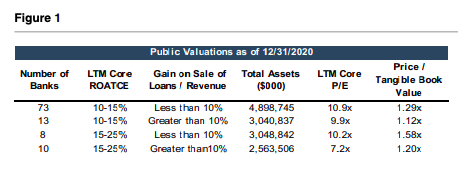

Non-bank mortgage companies found favor with the public markets in 2020 as beneficiaries of the sharp reduction in mortgage rates. In 2021 investor sentiment has faltered due to the impact of rising long-term rates on consensus earning estimates. Several companies undertook IPOs, while another company went public via merging with a SPAC. This expanded the group of non-bank mortgage companies from which to derive valuation multiples and benchmarking information. Figure 2 includes total return data for non-bank mortgage companies.

Notable transactions include the following: Rocket Mortgage (NYSE: RKT) raised $1.8 billion via an IPO at an approximate $36 billion valuation in August; Guild Holdings (NASDAQ: GHLD) raised ~$98 million in a November IPO; United Wholesale Mortgage (NYSE: UWM) went public in the largest SPAC deal in history (~$16 billion) that closed in 2021; and Loan Depot (NYSE: LDI) went public during February by raising $54 million.

Other pending IPOs based upon public S-1 filings include Caliber Home Loans and Better.com. Amerihome Mortgage Company had filed a registration statement but apparently obtained better pricing through an acquisition by Western Alliance Bancorp (NYSE: WAL) during February that was valued at ~ $1.0 billion at announcement, or about 1.4x the company’s tangible book value.

While this activity is positive for mortgage companies, the IPOs were downsized in terms of the number of shares sold with pricing below the initial target range or at the low end of the range as investors hedged how far and how fast earnings could fall in a rising rate environment.

For guideline M&A transactions, the data is often limited as there may only be a handful of transactions in a given year and even fewer with reported deal values and pricing multiples. However, meaningful data can sometimes be derived from announced transactions with transparent pricing and valuation metrics.

After deriving the “core” earnings estimate for the mortgage company as well as reasonable valuation multiples, other key valuation elements to consider include: any excess equity, mortgage servicing rights, unique technology solutions that differentiate the company, origination mix (refi vs. purchase; retail vs. correspondent or wholesale), geographic footprint of originations/ locations, and risk profile of the balance sheet and originations (for example, agency vs. non-agency loans).

Income Approach

Valuation methods under the income approach include those methods that provide for the direct capitalization of earnings estimates, as well as valuation methods calling for the forecasting of future benefits (earnings or cash flows) and then discounting those benefits to the present at an appropriate discount rate. For banks, the discounted cash flow (“DCF”) method can be a useful indication of value due to the availability and reliability of bank forecast/capital plans. However, due to the volatile and unpredictable nature of mortgage earnings, this method faces challenges when applied to a mortgage company. In certain situations, the DCF method may not be utilized due to uncertainties regarding the earnings outlook. In others, the DCF method may be applied with the subject company’s level of mortgage origination activity tied to a forecast for overall industry originations and historical gain on sale margins.

Given the potentially limited comparable company data and the difficulty associated with developing a long-term forecast for a DCF analysis, the single period income capitalization method may be useful.

This method involves determining an ongoing level of earnings for the company, usually by estimating an ongoing level of mortgage origination activity and a pretax margin and capitalizing it with a “cap rate”. The cap rate is a function of a perpetual earnings growth rate and a discount rate that is correlated with the entity’s risk. Whereas we would likely use recent earnings in the market approach, in the income capitalization method it makes sense to normalize earnings using a longer-term average, which considers origination and margin levels over an entire mortgage operating cycle.

Mortgage earnings and margins are cyclical. Due to the volatile nature of mortgage earnings, a higher discount rate is normally used. Therefore, a mortgage company’s earnings typically receive a lower multiple than a bank’s more stable earnings.

Conclusion

A mortgage subsidiary can be a beneficial tool for community banks to increase earnings and diversify revenue. This strategy, while clearly beneficial now, can be utilized throughout the business cycle. As rates fall and net interest income faces pressure, gains on the sale of loans should increase (and vice versa) to create counter-cyclical revenues. As we’ve discussed, the inherently volatile income from a mortgage subsidiary is not usually treated equally to net interest income in the public markets. Although, when it comes to price/tangible book value multiples, profitability is critical whether it is driven by mortgage activity or not. There are many factors to consider in valuing a mortgage company.

If you are considering this line of business to diversify your bank or desire a valuation of a mortgage operation, feel free to reach out for further discussion.

Originally appeared in Mercer Capital’s Bank Watch, February 2021.

Personal Goodwill: An Illustrative Example of an Auto Dealership

This article discusses important concepts of personal goodwill in divorce litigation engagements. The discussion relates directly to several divorce litigation cases involving owners of automobile dealerships. These real life examples display the depth of analysis that is critical to identifying the presence of personal goodwill and then estimating or allocating the associated value with the personal goodwill. The issues discussed here pertain specifically to considerations utilized in auto dealer valuations, but the overall concepts can be applied to most service-based industries.

It is important that the appraiser understands the industry and performs a thorough analysis of all relevant industry factors. It is also important to determine how each state treats personal goodwill. Some states consider personal goodwill to be a separate asset, and some do not make a specific distinction for it and include it in the marital assets.

Personal goodwill was an issue in several of our recent litigated divorce engagements. It is more prevalent in certain industries than others and varies from matter to matter. However, although there are several accepted methodologies to determine personal goodwill, there is not a textbook that discusses where it exists and where it doesn’t. Before any attempts to measure and quantify it, an important question to ask is “Does it exist?” Often with ambiguous concepts like personal goodwill, the adage “you know it when you see it” is most appropriate.

In this article, we examine personal and enterprise goodwill using a specific fact pattern unique to the auto dealership industry. Beyond this illustrative example, the analyses can be applied in other industries, but must be considered carefully for the unique facts and circumstances of each matter.

What Is Personal Goodwill?

Personal goodwill is value stemming from an individual’s personal service to a business and is an asset that tends to be owned by the individual, not the business itself. Personal goodwill is part of the larger bucket of an intangible asset known as goodwill. The other portion of goodwill, referred to as enterprise or business goodwill, relates to the intangible asset involved and owned by the business itself.1

Commercial and family law litigation cases aren’t typically governed by case law resulting from Tax Court matters and can differ by jurisdiction, but Tax Court decisions offer more insight into defining the conditions and questions that should be asked in an evaluation of personal goodwill. One seminal Tax Court case on personal goodwill is Martin Ice Cream vs. Commissioner.2 Among the Court’s discussions and questions to review were the following:

- Do personal relationships exist between customers/suppliers and the owner of a business?

- Do these relationships persist in the absence of formal contractual relationships?

- Does an owner’s personal reputation and/or perception in the industry provide intangible benefit to the business?

- Are practices of the owner innovative or distinguishable in his or her industry, such as the owner having added value to the particular industry?

Another angle with which to evaluate the presence of personal goodwill, specifically to professional practices, is provided in Lopez v. Lopez.3 Lopez suggests several factors that should be considered in the valuation of professional (personal) goodwill as:

- The age and health of the individual;

- The individual’s demonstrated earning power;

- The individual’s reputation in the community for judgement, skill, and knowledge;

- The individual’s comparative professional success

- The nature and duration of the professional’s practice as a sole proprietor or as a contributing member of a partnership or professional corporation.

Why Is Personal Goodwill Important?

Many states identify and distinguish between personal goodwill and enterprise goodwill. Further, numerous states do NOT consider the personal goodwill of a business to be a marital asset for family law cases. For example, a business could have a value of $1 million, but a certain portion of the value is attributable and allocated to personal goodwill. In this example, the value of the business would be reduced for personal goodwill for family law cases and the marital value of the business would be considered at something less than the $1 million value.

How Applicable/Prevalent Is Personal Goodwill in the Auto Dealer Industry?

In litigation matters, we always try to avoid the absolutes: always and never. The concept of personal goodwill is easier identified and more prevalent in service industries such as law practices, accounting firms, and smaller physician practices. Does that mean it doesn’t apply to more traditional retail and manufacturing industries? In each case, the fundamental question that should be first answered is “Is this an industry or company where personal goodwill could be present?”

For the auto dealer industry, the principal product, outside of the service department, is a tangible product – new and used vehicles. In order for personal goodwill to be present in this industry, the owner/dealer principal would have to exhibit a unique set of skills that specifically translates to the heightened performance of their business.

We are all familiar with regional dealerships possessing the name of the owner/dealer principal in the name of the business. However, just having the name on a business doesn’t signify the presence of personal goodwill. An examination of the customer base would be needed to justify personal goodwill. It would be more difficult to argue that customers are purchasing vehicles from a particular dealership only for the name on the door, rather than the more obvious factors of brands offered, availability of inventory, convenience, etc. An extreme example might be having a recognized celebrity as the name/face of the dealership, but even then, it would be debated how materially that affects sales and success.

Auto dealers attempt to track performance and customer satisfaction through surveys, which could provide an avenue to determine this value (if, for example, factors that influenced the decision to buy listed Joe Dealer as being their primary motivation) though this is still unlikely and would be subject to debate.

Another consideration of the impact of a dealer’s name on the success/value of the business would be how actively involved the owner/dealer principal is and how directly have they been involved with the customer in the selling process. Simply put, there should be higher bars to clear than just having the name in the dealership for personal goodwill to be present. In more obvious examples of personal goodwill in professional practices, the customer usually interacts directly with the owner/professional such as with the attorney or doctor in our previous examples. How often does the customer of an auto dealership come into contact or deal directly with the owner/dealer principal, or do they generally engage with the salespeople, service manager, or the general manger?

Another factor that often helps identify the existence of personal goodwill is the presence of an employment agreement and/or non-compete agreement. The prevailing thought is that an owner of a business without these items would theoretically be able to exit the business and open a similar business and compete directly with the prior business. Neither of these items typically exist with an owner of an auto dealership. However, owners of auto dealerships must be approved as dealer principals by the manufacturer.

The transferability of a dealer principal relationship is not guaranteed, and certainly an existing dealer principal would not be able to obtain an additional franchise to directly compete with an existing franchise location of the same manufacturer for obvious area of responsibility (AOR) constraints. So, does the fact that most dealer principals don’t have an employment or non-compete agreement signify that personal goodwill must be present? Not necessarily. Again it relates back to the central questions of whether an owner/dealer principal is directly involved in the business, has a unique set of skills that contributed to a heightened success of the business, and does that owner/dealer principal have a direct impact on attracting customers to their particular dealership that could not be replicated by another individual.

Conclusion

Personal goodwill in an auto dealership, and in any industry, can become a contested item in a litigation case because it can reduce the enterprise value consideration, reduced by the amount allocated to personal goodwill. As much as the allocation, quantification, and methodology used to determine the amount of personal goodwill will come into question, several central questions should be examined and answered before simply jumping to the conclusion that personal goodwill exists.

Instead of arguing whether the value of an auto dealership should be reduced by some percentage, the real debate should center around the examination of whether personal goodwill exists in the first place. The difference in reports from valuation for experts in litigation matters generally falls within the examination and support of the assumptions (that lead to differences in conclusions). If present, personal goodwill for an auto dealership, or any company in any industry for that matter, must exist beyond just having the owner’s name in the title of the business.

1 In the auto dealer industry, goodwill and other intangible assets are referred to as Blue Sky value.

2 Martin Ice Cream Co. v. Commissioner, 110 T.C. 189 (1998).

3 In re Marriage of Lopez, 113 Cal. Rptr. 58 (38 Cal. App. 3d 1044 (1974).

Critical Issues in the Trucking Industry – 2020 Edition

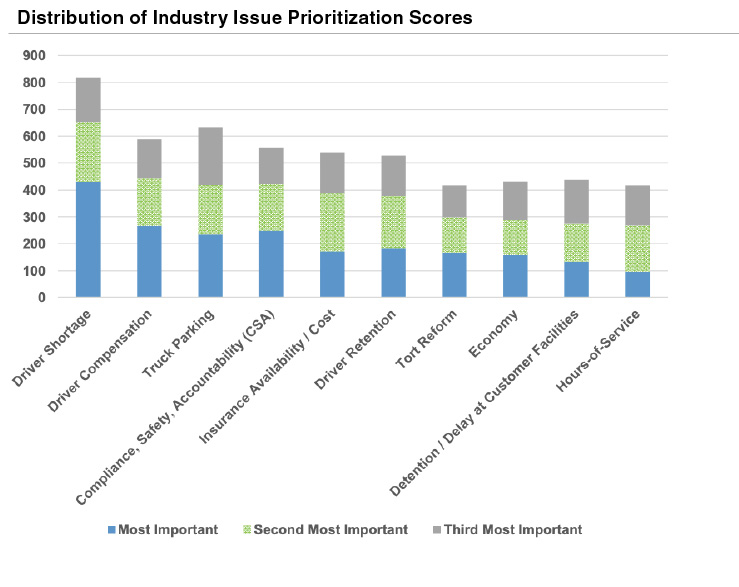

Every year the American Transportation Research Institute (“ATRI”) publishes its report, Critical Issues in the Trucking Industry. A key piece of this annual report is a survey of key risk factors in the industry. While some of the risks of 2020 were not anticipated at the beginning of the year, some of the industry’s largest risk factors remain major concerns.

Driver shortages and driver compensation continue to be at the forefront of peoples’ minds. This year marks the fourth year that driver shortages have topped the list and over a quarter of survey participants marked it as one of their three largest concerns. While parts of the industry have been hit hard by COVID-19 (for example, automobile shippers or marine port logistics companies), freight demand continues to grow. The pool of available drivers – already pruned by rules changes and more stringent drug testing – shrunk further as COVID limited company’s abilities to hire and train more drivers. The American Trucking Association (“ATA”) estimated that the driver shortfall at over 60,000 drivers.

Driver compensation ranked as the second largest concern, up from the third largest in 2019. Driver compensation and driver shortages are closely linked – in order to encourage driver retention, companies are reconsidering base pay and benefits.

Driver compensation ranked as the second largest concern, up from the third largest in 2019. Driver compensation and driver shortages are closely linked – in order to encourage driver retention, companies are reconsidering base pay and benefits.

Truck parking first appeared on the top ten list in 2012. With just over 20% of respondents listing it as one of their top three concerns, truck parking availability reached its highest position yet. Once again, the COVID-19 pandemic underlies part of the issue – many states closed rest areas during the early stages of the pandemic. Lack of truck parking was a greater concern among owner-operators and independent contractors than among company drivers.

Compliance, safety, and accountability have been a top five concern for seven of the last ten years and has ranked in the top ten since 2010. The FMCSA has updated standards during its ten-year history, but transparency, details, and legal classifications continue to cause uncertainty and unrest in the industry.

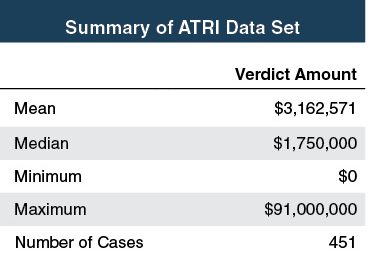

The cost and availability of insurance ranked as the fifth highest concern. In a 2019 report, ATRI estimated that insurance costs per mile increased 12% between 2017 and 2018 and 5.6% on a compound annual basis since 2013. The impact of large court verdicts, increased vehicle values, and higher levels of traffic have all driven insurance prices up.

COVID-19 ranked 13th in the survey, although the impacts of the pandemic bleed through into other industry concerns. ATRI found that the COVID-19 pandemic tended to impact smaller carriers and owner-operators on a larger scale than bigger companies.

ATRI ultimately discusses the ten highest-ranked concerns in its report. The transportation and logistics industry continues to evolve as new risks and concerns rise in importance.

Patel v. Patel

In this case, the parties raised the matter to appeals for two issues: 1) whether the trial court erred in awarding Wife alimony in futuro of $7,500 per month, and 2) whether Wife is entitled to attorney’s fees.

The parties divorced after a 13 year marriage in which the family was initially solely supported by Wife’s $40,000 annual income. However, at the time of divorce, Husband was earning approximately $850,000 per year and Wife was not employed but was a full-time student (due to frequent moves but also a mutual decision). The trial court found that long-term alimony was appropriate given Wife’s contribution to Husband’s earning capacity, her inability to achieve his earning capacity despite her efforts at education, and the parties’ relatively high standard of living during the marriage.

At the beginning of the marriage, the husband was a full-time medical student earning no income. Across the husband’s education and career, the parties moved from Georgia to Kentucky to Florida to Ohio, and finally to Jackson, Tennessee. During separation, Wife enrolled in a college to obtain a Bachelor’s Degree in Accounting and hoped to eventually enroll in a Master’s Degree program. Wife was a full-time student at the time of trial.

Husband testified that he planned to move to Florida and his base pay upon moving to Florida after the divorce would be approximately $450,000. Husband admitted, however, that this figure did not account for the bonuses that Husband had historically received and had caused his income to increase substantially. Wife’s sole income at the time of the divorce amounted to approximately $2,000 per year in dividends.

Each of the parties created a budget of estimated forward expenses. During proceedings, each party claimed that the other was controlling the parties’ finances, refusing to permit the other to fund basic expenses. With regard to expenses, Husband claimed as an expense $10,000 per month for savings in the event that he is sued for malpractice and his insurance does not cover the entire award, costs for his parents’ health insurance, considerable maintenance on his car, and large charitable contributions. With regard to Wife’s expenses, Husband contended that they were inflated over historical actual expenses. Husband testified that expenses incurred by Wife following the separation were for extravagant gifts to family that were not representative of the parties’ lifestyle throughout the marriage.

Demonstrating the marital estate and standard of living, the parties had accumulated a level of wealth during the marriage, including two cars, several retirement accounts, and savings accounts. Husband paid off the mortgage of their Jackson, Tennessee home during the pendency of the divorce. As such, the parties had no debt at the time of the divorce and considerable assets. During the marriage, the parties also took several vacations, both in the United States and outside the country.

The trial court made the following statement on the earnings capacity of each party:

Husband’s gross earning capacity is currently about $850,000 per year. His net income based on his effective tax rate for 2016 would be in the range of about $550,000. Husband owes no debt, and will have significant assets from the property division. Wife’s current income is zero essentially, but when she finishes school, if she is able to obtain employment in her field, and achieve a CPA designation, her gross income should be in the range of $55,000 according to testimony. If she pursues a Master’s Degree and achieves it, her earning capacity could increase to $85,000 per year. Thus, there is a significant difference between the Husband’s and Wife’s earning capacity. Their obligations are about the same.

The appellate court made the following conclusion on earnings capacity:

..the evidence does not clearly and convincingly show that Wife did not significantly contribute to Husband’s career and resulting earning capacity. Rather, the evidence supports the trial court’s finding that Wife made tangible and intangible contributions to the Husband’s increased earning capacity.

Considering the factors for spousal support unique to this matter, the trial court found that the alimony in futuro of $7,500 per month alimony was appropriate given: 1) Wife’s contribution to husband’s earning capacity, 2) Wife’s inability to achieve Husband’s earning capacity despite her efforts at education, and 3) the parties’ relatively high standard of living during the marriage. Discerning no reversible error, the appellate court affirmed the trial court in all respects. Also, given the considerable property awarded to Wife in the divorce, the appellate court declined to award attorney’s fees incurred on appeal in this case.

A financial expert witness can significantly assist in the court’s determination of divorcing parties’ ability and need to pay in its determinations for spousal support. The analysis is a complex matter and calls for the expertise and analysis of a financial expert. Refer to our piece, “What Is a Lifestyle Analysis and Why Is it Important?” for more information about the process, analysis, and support that can be provided by a financial expert.

Fresh Start Accounting Valuation Considerations: Measuring the Reorganization Value of Identifiable Intangible Assets

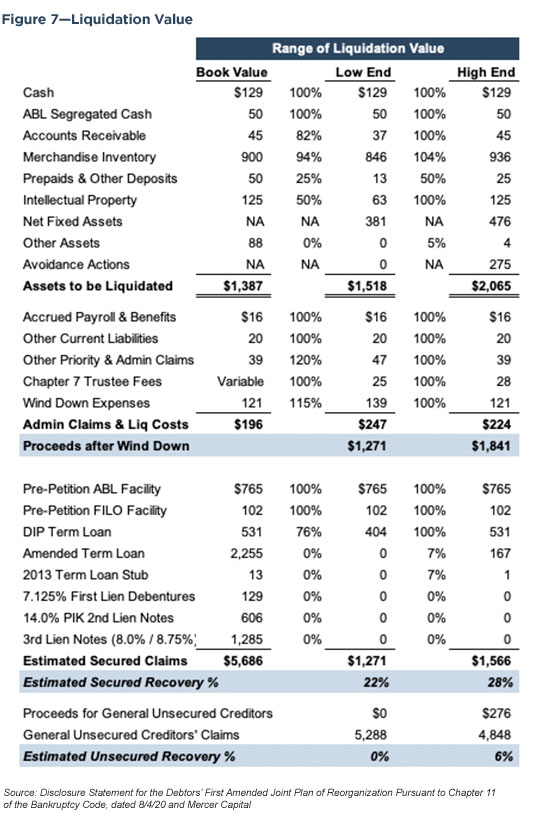

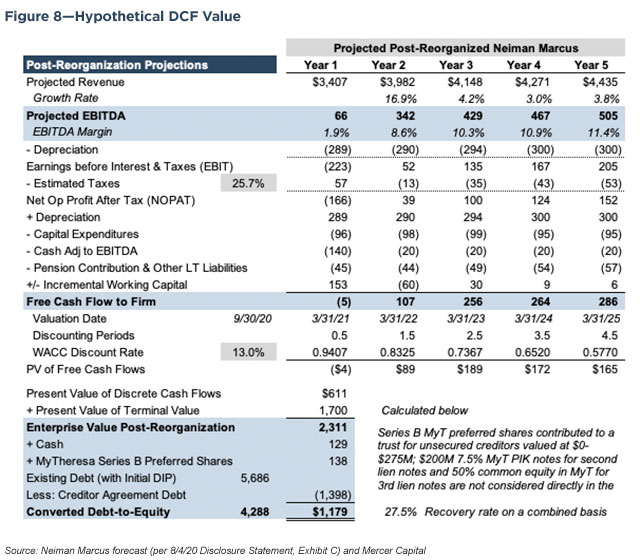

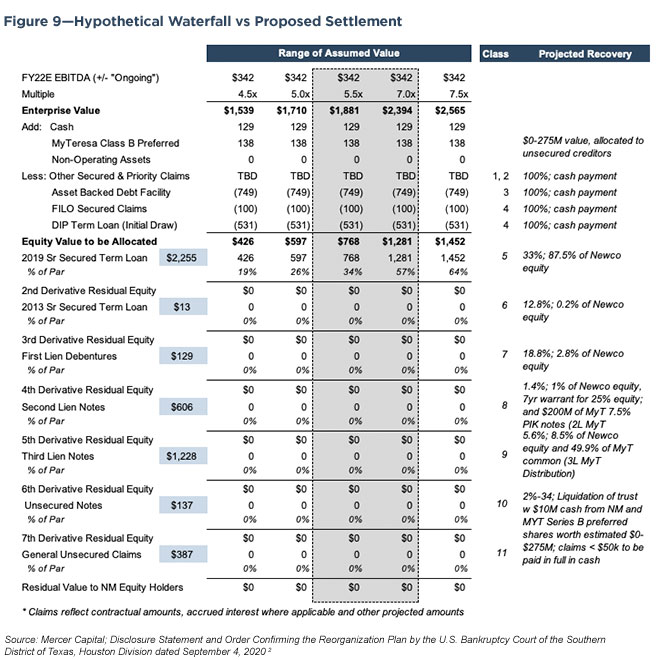

Upon emerging from Chapter 11 bankruptcy, companies are required to apply the provisions of Accounting Standards Codification 852, Reorganizations. Under this treatment, referred to as “fresh start” accounting, companies exiting Chapter 11 are required to re-state assets and liabilities at fair value, as if the company were being acquired at a price equal to the reorganization value. As a result, two principal valuation-related questions are relevant for companies in bankruptcy:

- Reorganization Value – As noted in ASC 852, Reorganizations, reorganization value “generally approximates the fair value of the entity before considering liabilities and approximates the amount a willing buyer would pay for the assets of the entity immediately after the restructuring.” (ASC 852-05-10) Discounted cash flow analysis is the principal technique for measuring reorganization value. In certain cases, depending on the nature of the business and availability of relevant guideline companies, a method under the market approach may also be appropriate. A reliable cash flow forecast and estimate of the appropriate cost of capital are essential inputs to measuring reorganization value.

- Identifiable Intangible Assets – When fresh-start accounting is required, it may be appropriate to allocate a portion of the reorganization value to specific identifiable intangible assets such as tradenames, technology, or customer relationships. We discuss valuation techniques for identifiable intangible assets in the remainder of this article.

Measuring the Fair Value of Identifiable Intangible Assets

When valuing identifiable intangible assets, we use valuation methods under the cost, income, and market approaches.

The Cost Approach

The cost approach seeks to measure the future benefits of ownership by quantifying the amount of money that would be required to replace the future service capability of the subject intangible asset. The assumption underlying the cost approach is that the cost to purchase or develop new property is commensurate with the economic value of the service that the property can provide during its life. The cost approach does not directly consider the economic benefits that can be achieved or the time period over which they might continue. It is an inherent assumption with this approach that economic benefits exist and are of sufficient amount and duration to justify the developmental expenditures.

Methods under the cost approach are frequently used to measure the fair value of assembled workforce, proprietary software, and other technology-related assets.

The Market Approach

The market approach provides an indication of value by comparing the price at which similar property has been exchanged between willing buyers and sellers. When the market approach is used, an indication of value of a specific intangible asset can be gained from looking at the prices paid for comparable property.

Since there is rarely an active market for identifiable intangible assets apart from broader business combination transactions, valuation methods under the market approach are not commonly used to value identifiable intangible assets.

However, available market data, such as observed royalty rates in licensing transactions, is an important input in valuation methods under the income approach such as the relief-from-royalty method. Other market-derived data helps to inform estimates of the cost of capital and other valuation inputs, as well.

The Income Approach

The income approach focuses on the capacity of the subject intangible asset to produce future economic benefits. The underlying theory is that the value of the subject property can be measured as the present worth of the net economic benefits to be received over the life of the intangible asset.

Using valuation methods under the income approach, we estimate future benefits expected to result from the subject asset and an appropriate rate at which to discount these expected benefits to the present. The most common valuation methods under the income approach are the relief from royalty method and multi-period excess earnings method, or MPEEM.

- The relief from royalty method seeks to measure the incremental net profitability available to the owner of the subject intangible asset by avoiding the royalty payments that would otherwise be required to enjoy the benefits of ownership of the asset. When applying the relief from royalty method requires specification of three variables: 1) The expected stream of revenue attributable to the identifiable intangible asset, 2) An appropriate royalty rate to apply to that revenue stream, and 3) An appropriate discount rate to measure the present value of the avoided royalty payments. The relief from royalty method is most commonly used to value tradename and technology assets for which market-based royalty rates may be observed.The MPEEM is a form of discounted cash flow analysis that measures the value of an intangible asset as the present value of the incremental after-tax cash flows attributable only to the subject asset. In order to isolate those cash flows, we first develop a forecast of the expected revenues and associated operating costs attributable to the asset.

- Next, we apply contributory asset charges to reflect the economic “rent” for use of the other assets that must be in place to generate the projected operating earnings. In other words, the MPEEM recognizes that the subject identifiable intangible asset generates operating earnings only in concert with other assets of the business.

- Finally, we reduce the net after-tax cash flows attributable to the subject identifiable intangible asset to present value using a risk-adjusted discount rate. The indicated value is the sum of the present values of the “excess earnings” of the expected life of the subject asset.

We often apply the MPEEM to measure the fair value of customer relationship and technology intangibles.

Conclusion

The valuation techniques for identifiable intangible assets are rooted in the fundamental elements of business valuation, cash flow and risk, under the cost, market, and income approaches. However, when valuing identifiable intangible assets, we use valuation methods adapted to the unique attributes of those assets.

Estate Planning When Bank Stocks Are Depressed

Maybe not for the best of reasons, the stars have aligned for bank investors who have significant interests in banks to undertake robust estate planning this year.

Bank stock valuations are depressed as a result of the recession that developed from the COVID-19 policy responses, including a return to a zero interest rate policy (“ZIRP”) that is now known as the effective lower bound (“ELB”). The result is severe compression in net interest margins (“NIMs”), while the extent of credit losses will not be known until 2021 or perhaps even 2022.

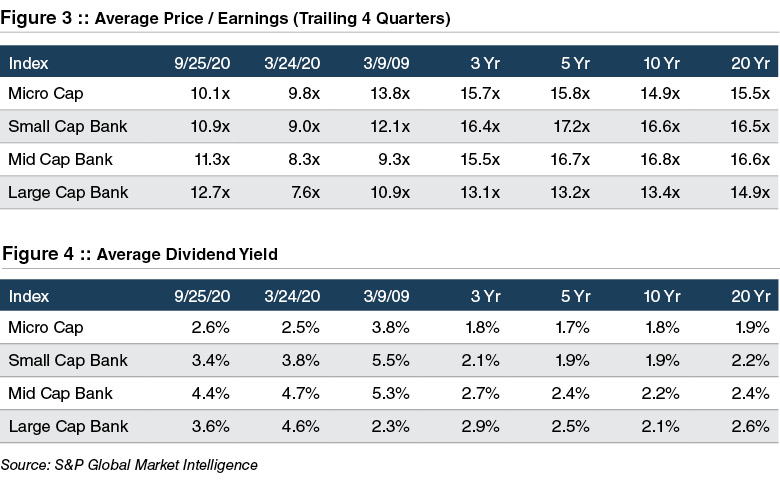

As shown in Figure 1, bank stocks have produced a negative total return that ranges from -27% for the twelve months ended September 25, 2020 for the SNL Large Cap Bank Index to -36% for the SNL Mid Cap Bank Index. At the other extreme are tech stocks. The NASDAQ Composite has produced a one-year total return of 35%–a 70% spread between the two sectors.

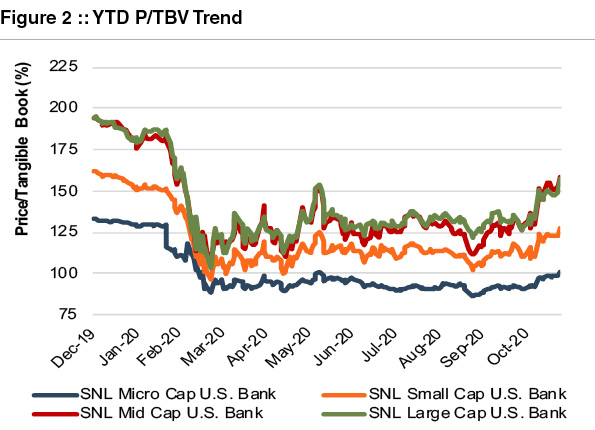

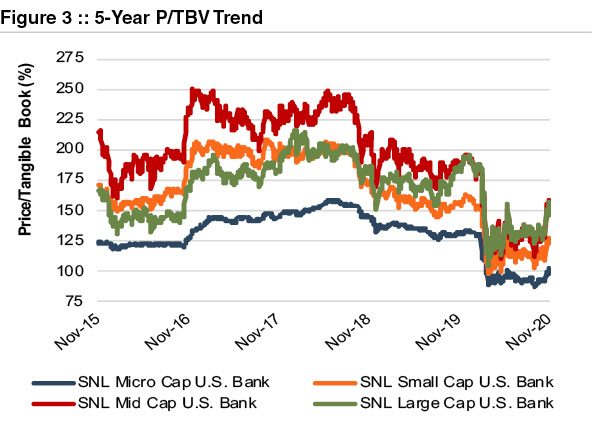

Valuations for banks are depressed and are comparable to lows observed on March 24, 2020 when market panic and forced selling by levered investors peaked and March 9, 2009 when investors feared a possible nationalization of the large banks. Price-to-tangible book value (“P/TBV”) multiples are presented in Figure 2, while price-to-earnings (“P/E”) ratios based upon the last 12-month (“LTM”) earnings are presented in Figure 3. (Note—while P/TBV multiples are little changed from March 24, 2020, P/E ratios have increased because reserve building and reduced NIMs have reduced LTM earnings).

No one knows the future, but assuming reversion to the mean eventually occurs bank stocks could rally as earnings improve once credit costs decline even if NIMs remain depressed, resulting in higher earnings and multiple expansion. Relative to ten-year average multiples based upon daily observations, banks are 30-40% cheap to their post-Great Financial Crisis trading history.

In effect, current gifting and other estate planning could lock in significant tax benefits assuming a Japan and Europe scenario does not develop in the U.S. where banks are “re-rated” and underperform for decades.

A second reason to consider significant estate planning transactions this year is the potential change in Washington if 2021 sees a Biden Administration backstopped with a Democrat-controlled Senate and House.

Vice President Biden’s proposed estate tax changes include the elimination of basis step-up, significant reductions to the unified credit (the amount of wealth that passes tax-free from estate to beneficiary) and gift tax exemption, and increasing current capital gains tax rates to ordinary income levels for high earning households. The cumulative effect of these changes is a substantial increase in high net worth clients’ estate tax liabilities if Biden’s current proposals become law.

Basis step-up is a subtle but important feature of tax law. Unusual among industrialized nations, in the United States the assets in an estate pass to heirs at a tax value established at death (or at an alternate valuation date). Even though no tax is collected on the first $11.6 million per person, the tax basis for the heir is “stepped-up” to the new value established at death. Other countries handle this issue differently, and Biden favors eliminating the step-up in tax basis. Further, he prefers taxing the embedded capital gain at death. Canada, for example, does this – treating a bequest as any other transfer and assessing capital gains taxes to the estate of the decedent.

Fortunately, there are several things bank shareholders can do now to minimize exposure to these potential tax law changes. Taking advantage of the current high-level of gift tax exemptions ($11.58 million per individual or $23.16 million per married couple) could save millions in taxes if Biden’s proposed lower exemption of $3.5 million per individual becomes law.

Other options include the formation of trusts or asset holding entities to transfer wealth to the next generation in a tax-efficient manner. Proper estate planning can mitigate the adverse effects of higher taxes on wealth transfers, but the window to do so may be closing if we have a regime change later this year.

Further, the demand (and associated cost) for estate planning services may go up significantly in November, so you need to apprise your clients of these potential changes before it’s too late.

In the 1990s, the unified credit (the amount of wealth that passes tax-free from estate to beneficiary) was only $650 thousand, or $1.3 million for a married couple. The unified credit was not indexed for inflation, and the threshold for owing taxes was so low that many families we now consider “mass-affluent” engaged in sophisticated estate tax planning techniques to minimize their liability.

Then in 2000, George W. Bush was elected President, and estate taxes were to be phased out. Over the past decade, the law has changed several times, but mostly to the benefit of wealthier estates. That $650 thousand exemption from estate taxes is now $11.6 million. A married couple would need a net worth of almost $25 million before owing any estate tax, such that now only a sliver of bank stock investors require heavy duty tax planning.

That may all be about to change.

Vice President Biden has more than gestured that he plans to increase estate taxes by lowering the unified credit, raising rates, and potentially eliminating the step-up in basis that has long been a feature of tax law in the United States.

Talk is cheap. But investors take heed; now may be the time to execute rather than plan.

Originally appeared in Mercer Capital’s Bank Watch, September 2020.

Four Reasons to Consider a Stock Repurchase Program

Bank stocks rallied in the first few weeks of November 2020 as the market’s Thanksgiving dinner came early, and it digested several issues including positive news on the COVID-19 vaccine candidates. While significant uncertainty still exists on credit conditions, COVID-19, and the economic outlook, bank valuations and earnings expectations also benefitted from the yield curve steepening as evidenced by the 10-year Treasury moving up from ~50 bps in early August to ~85 bps in mid-November.

Despite the recent rise in bank stock pricing, bank stock valuations are still depressed relative to pre-COVID levels as a result of the recession that developed from the pandemic and ensuing policy responses. A primary headwind for banks is the potential compression in net interest margins (“NIMs”) following a return to a zero interest rate policy (“ZIRP”) that is now known as the effective lower bound (“ELB”). Additionally, credit risk remains heightened for the sector compared to pre-pandemic levels as the extent of credit losses resulting from the pandemic and economic slowdown will not be known until 2021 or perhaps even 2022.

Amidst this backdrop, many banks and their directors are evaluating strategic options and ways to create value for shareholders. While the Federal Reserve has prohibited the largest U.S. banks from share repurchases, the current environment has prompted many community banks to announce share buyback plans. According to S&P Global Market Intelligence, more than forty U.S. community banks announced buyback plans in the third quarter and the trend has continued in the fourth quarter with another 36 buyback announcements, including new plans, extensions of existing plans, and reinstatements of previously suspended plans, in October. In our view, there are four primary reasons that many community and regional banks are announcing or expanding share repurchase programs in the current environment.

1) Valuations are Lower Relative to Historical Levels

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the banking sector has underperformed the broader market due to concerns on credit quality and a prolonged low-interest rate environment. Despite the November rally, bank stocks are still trading at lower multiples than observed in recent years. Furthermore, many banks are finding themselves with excess liquidity in light of weaker loan demand and growing deposits.

In a depressed price environment, share repurchases can be a favorable use of capital, particularly when pricing is at a discount to book value and is accretive to book value per share. As shown in the chart below, the average P/TBV multiple has declined for all of the SNL market capitalization bank indices since the beginning of 2020. The decline has been most pronounced for the Micro Cap index, with the average P/TBV multiple for banks with a total market capitalization of less than $250 million falling from 133% to 102%.

2) Favorable Tax Environment for Shareholders Seeking Liquidity

Capital gains tax rates are low relative to historical levels and the potential for higher capital gains tax rates has risen under President-elect Biden. As part of his tax plan, Biden has proposed increasing the top tax rate for capital gains for the highest earners from 23.8% to 39.6% (akin to ordinary income levels), which would be the largest increase in capital gains rates in history. While the ability for Biden’s tax plan to become reality is uncertain, many community banks have an aging shareholder base with long-term capital gains and it is an issue worth watching and planning for as poor planning can leave significant tax consequences for the shareholder or his or her heirs. A share repurchase program can provide liquidity to shareholders who may be apt to take advantage of the current capital gains rates that are low by historical standards and lower than the rates proposed by President-elect Biden.

3) Relatively Low Borrowing Costs and Sufficient Capital for Many Community Banks

Despite the unique issues brought about by the pandemic and the uncertain economic outlook, many community banks are well capitalized and have “excess” capital at the bank level and perhaps even an unleveraged holding company. We have written previously about the idea of robust stress testing and capital planning given the economic environment but note that a recent survey indicated that most bankers believe capital levels are sufficient to weather the economic downturn. Our research also indicates that rates on subordinated debt issuances issued in September of 2020 averaged ~5% compared to ~6% average for 2018 and 2019. These lower borrowing costs and ample capital for many banks in combination with lower share prices enhance the potential internal rate of return for share repurchases when compared to other strategic alternative uses of capital.

4) Enhancing Shareholder Value and Liquidity

Board members and management teams face the strategic decision of allocating capital in a way that creates value for shareholders. Potential options include growing the balance sheet organically or through acquisition (perhaps a whole bank or branch), payment of dividends, or a stock repurchase program. While M&A has been a constant theme, activity has slowed during the COVID-19 pandemic and Bank Director’s 2021 Bank M&A Survey noted that only ~33% say their institution is likely to purchase a bank by the end of 2021, which was down from the prior year’s survey (at ~44%). Key challenges to M&A in the current environment include conducting due diligence and evaluating a seller’s loan portfolio in light of COVID-19 impacts and economic uncertainty.

Organic loan growth expectations have also been muted for many banks in light of the economic slowdown resulting from COVID-19. With organic and acquisitive balance sheet growth appearing less attractive for many banks in the current environment, dividends and share repurchases have climbed up the strategic option list for many banks. A share repurchase program can have the added benefit of enhancing liquidity and marketability of illiquid shares, which potentially enhances the valuation of a minority interest in the bank’s stock.

Conclusion

If your bank’s board does implement a share repurchase program, it is critical for the board to set the purchase price based upon a reasonable valuation of the shares. While ~5,000 banks exist, the industry is very diverse and differences exist in financial performance, risk appetite, growth trajectory, and future performance/outlook in light of the shifting landscape. Valuations should understand the common issues faced by all banks – such as the interest rate environment, credit risk, or technological trends – but also the entity-specific factors bearing on financial performance, risk, and growth that lead to the differentiation in value observed in both the public and M&A markets.

At Mercer Capital, valuations are more than a mere quantitative exercise. Integrating a bank’s growth prospects and risk characteristics into a valuation analysis requires understanding the bank’s history, business plans, market opportunities, response to emerging technological issues, staff experience, and the like.

For those banks considering a share repurchase program, Mercer Capital has the experience to provide an independent valuation of the stock that can serve to assist the Board in setting the purchase price for the share repurchase program.

Originally appeared in Mercer Capital’s Bank Watch, November 2020.

What RIAs Need to Know About Current Estate Planning Opportunities

Estate and tax planning matters are an important component of the overall financial plan for many RIA clients. The current tax policy and market environment create unique estate planning opportunities that may not last if economic conditions normalize or if Biden wins in November. This webinar addresses the available opportunities that RIA principals and advisors should be aware of in the current environment.

Original air date: October 28, 2020

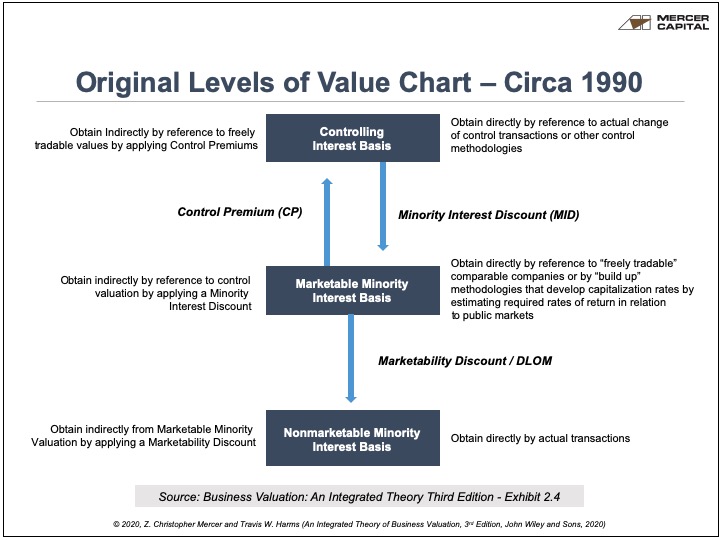

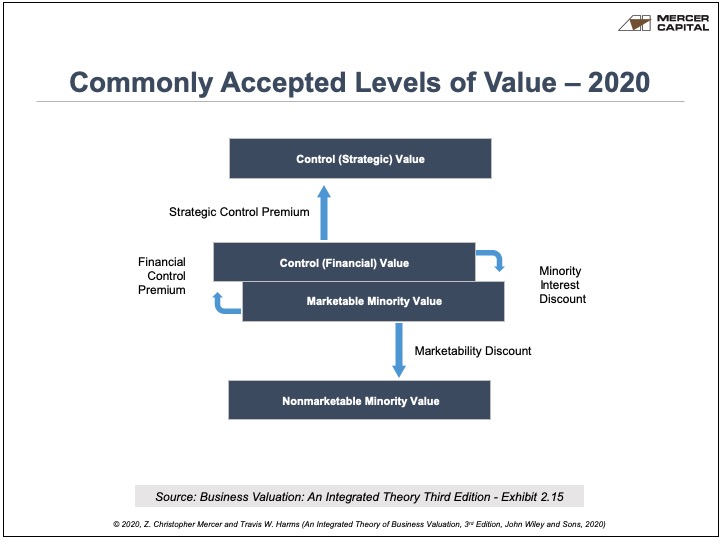

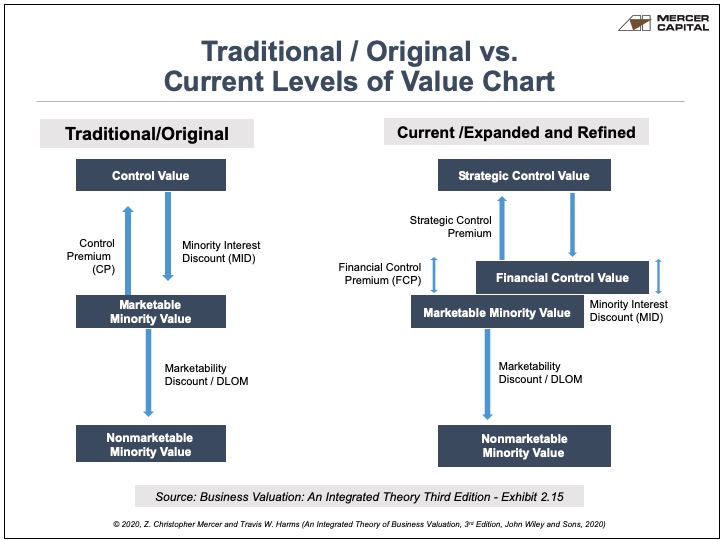

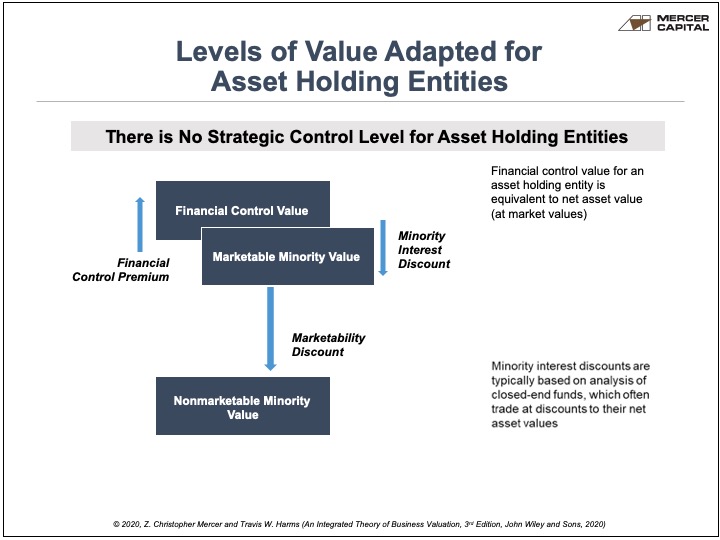

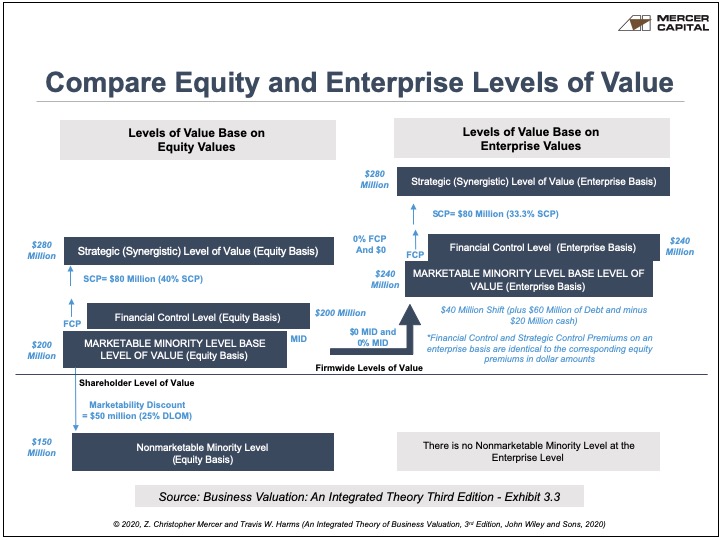

Premise of Value: Why It Is a Critical Aspect of Business Continuity and Financial Restructuring

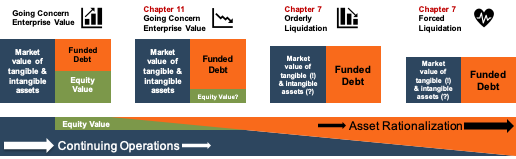

The conventions for defining value may never be more important than when making decisions related to business continuity and financial restructuring. Countless clients have demonstrated a sense of confusion regarding the various descriptors of value used in valuation settings. More than a few valuation stakeholders have mused that the value of anything (a business or an asset as the case may be) should be an absolute numerical expression and unambiguous in meaning. Unfortunately for those seeking simplicity in a trying time, the conditional cliché “it depends” is critical when defining value for the assessment of bankruptcy decisions and workout financing. The elements that underpin the Premise of Value provide a convenient base for introducing some of the vocabulary used in the bankruptcy and restructuring environment. Gaining a thorough familiarity with the Premise of Value provides a cornerstone for understanding the financial considerations employed in valuing business assets and evaluating financial options.

Defining value is a science of its own and can be subject to debate based on facts and circumstances. With respect to business enterprises and assets, as well as business ownership interests, there are numerous defining elements of value. These elements generally include the Standard of Value, the Level of Value, and the Premise of Value. More confusing is that real property appraisers, machinery & equipment appraisers and corporate valuation advisors may not use the same value-defining nomenclature and may have varied meanings for similar vocabulary. When the question of business value or asset value arises, the purpose of the valuation, the venue or jurisdiction in which value is being determined and numerous other facts and circumstances have a bearing on the defining elements of value.

Everyone has seen the “inventory liquidation sale” sign or the “going out of business” sign in the shop window. For the merchant and the merchant’s capital providers, the ramifications of how assets are monetized for the purposes of optimizing returns on and of capital is a key focus of the valuation methods employed in the restructuring and bankruptcy environment. The international glossary of business valuation terms defines the Premise of Value and its components as follows:

- Premise of Value – an assumption regarding the most likely set of transactional circumstances that may be applicable to the subject valuation; for example, Going Concern, liquidation

- Going Concern Value – the value of a business enterprise that is expected to continue to operate into the future. The intangible elements of Going Concern Value result from factors such as having a trained work force, an operational plant, and the necessary licenses, systems, and procedures in place.

- Liquidation Value – the net amount that would be realized if the business is terminated and the assets are sold piecemeal. Liquidation can be either “orderly” or “forced.”

- Orderly Liquidation Value – liquidation value at which the asset or assets are sold over a reasonable period of time to maximize proceeds received.

- Forced Liquidation Value – liquidation value, at which the asset or assets are sold as quickly as possible, such as at an auction

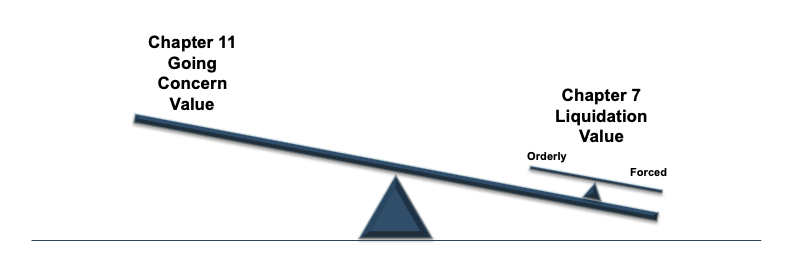

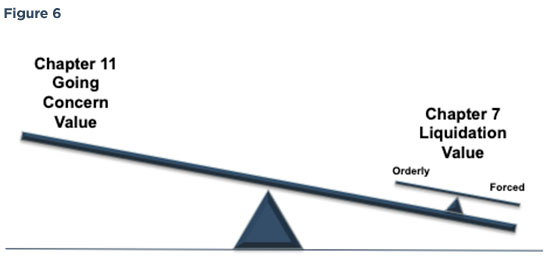

The Premise of Value is a swing consideration for distressed businesses and their lenders. For businesses in financial distress, achieving a return on capital shifts to the priority of asset protection and capital value preservation via a deliberate plan to mitigate downside exposures. In most situations where a business is dealing with an existential financial threat, the preference for the business is to remain a Going Concern (at least initially), whereby the business continues to operate as a re-postured version of its former self. In the context of bankruptcies and/or restructurings, the business that remains a Going Concern is referred to as the Debtor in Possession (DIP).

DIPs remain a Going Concern using the protection of Chapter 11 bankruptcy to achieve a fresh start where their financial obligations are restructured through modification and/or specialized refinancing. Chapter 11 involves a detailed plan of reorganization, which may be administered by a trustee and is ultimately governed under the specialized legal oversight of the courts. Reorganization under Chapter 11 is the preferred first step for most operating enterprises whose business assets are purpose?specific and for which the break-up value of the assets would be economically punitive to capital investors. Intuitive to the Going Concern premise are valuation methods and analyses that study potential business outcomes using detailed forecasts and the corresponding potential of the resulting cash flows to service the necessary financing to achieve the outcome. One valuation discipline among numerous possibilities is the establishment and testing of a value threshold at which the capital returns are deemed adequate to their respective providers (e.g. an IRR analysis) based on the risks incurred. If remaining a Going Concern delivers an acceptable rate of return under a plan of reorganization, then liquidation might be avoided or forestalled.

The alternative to remaining a Going Concern involves the process of liquidation. In bankruptcy terms, a business entity files for Chapter 7 and begins the cessation of business operations and seeks a sale of assets to re-pay creditors based the creditors’ respective position in the capital stack. The “liquidation” premise is generally a value-compromising proposition for the bankruptcy stakeholders with the economic consequences are scaled to whether the liquidation is achieved in an orderly process or a forced process.

Modern, global economies and increasingly technology inspired business models have resulted in a certain amount of disruption, the consequences of which often compromise the value of purpose-specific business assets in obsoleting or excess-capacity industries (e.g. coal in the face of growing energy alternatives and concerns for climate change). Assets that have productive capacity are typically sold in an orderly market and may achieve a value commensurate with the capital asset expenditures expectations of industry market participants. Real property assets and operating assets that can be successfully transitioned or re-purposed are often liquidated in an orderly fashion to maximize value. Specialized assets and/or assets with inferior productive capacity or which are positioned in unfavorable circumstances likely lack the ability to attract buyers due to the deficiencies and/or inefficiencies of relevant markets. Accordingly, the time value of money and the demands of the most senior creditors may suggest or dictate that a forced liquidation sooner is more favorable than a deferred outcome.

Most restructuring and bankruptcies involve a total rationalization of operating assets and business resources. For large integrated businesses, it often occurs that a combination of value premises applies to differing types of tangible and intangible assets based on the go-forward strategy of the business and the availability of markets in which to monetize assets. For example, an initial liquidation may occur with respect to certain business operations and properties to create the resources necessary to achieve debt restructuring or DIP financing. Accordingly, advisory engagements often take into consideration a wide range of options based on the timing of asset sales and the sustainability of continuing operations. The Premise of Value is a quiet but critical defining element for assessing the collective value proposition associated with a plan of reorganization.

Many bankruptcy advisory projects necessarily involve comparing the Going Concern value to Liquidation value. Each premise involves an inherently speculative set of underlying models and assumptions about the performance of the business and/or the timing and exit value achieved for business assets. And, each may be developed using a variety of scenarios with differing outcomes and event timing. Setting aside the qualitative aspects of decision making, the Premise of Value with the best outcome is typically the path of pursuit based on the necessity for an objective criterion required under the legalities of the bankruptcy process and the priority claims of creditors.

A fundamental understanding of the defining elements of value is critical to distressed businesses and their creditors. Valuation advisors are required to clearly detail the defining elements of value employed in the determination of asset values and enterprise valuations. The Premise of Value must be comprehended in the context of other defining elements of value. If you have a question concerning the design and valuation of varying plans of reorganization or bankruptcy strategies, please contact Mercer Capital’s Transaction Advisory Group.

Subdued M&A Activity in the First Half of 2020

U.S. M&A activity slowed sharply in the second quarter due to the economic shock resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. Activity – especially involving lower-to-middle market businesses – is expected to remain muted for the duration of 2020 and throughout 2021 unless more effective therapeutics and/or vaccines are developed that facilitate a more bullish sentiment than currently prevails.

Although evidence is currently obscure, M&A markets appear to reflect wider bid-ask spreads among would-be sellers and buyers. Sellers are too fixated on what their business might have transacted for in 2019 while buyers expect to pay less as a result of declining performance and higher uncertainty regarding the magnitude and duration of the current economic malaise.

Numerous industries lack sufficiently motivated strategic buyers willing to overlook concerns for their existing businesses to say nothing of the integration of new business. On the other hand, certain financial buyers seem to have returned to the market looking to deploy capital at attractive valuations when and where acquisition financing is available at reasonable terms and pricing.