Welcome, Paul. Tell us a little bit about yourself and your practice.

Paul Hood: I like to describe myself in two ways. First, I’m a recovering tax lawyer. Second, I’m a purposeful estate planner. I believe in focusing much more attention on the human side of estate planning because it’s the most challenging part of estate planning, much more so than the tax planning and property disposition aspects of estate planning. But very few estate planners want to delve sufficiently deeply into the human side because it involves dealing with real human emotions, including our own.

Along the course of my life, I’ve been a father, husband, lawyer, trustee, director, president, partner, trust protector, director of planned giving, expert witness, agent, professor, judge, juror and a defendant, and I use this life experience in these myriad roles to guide others. I help people pursue a "good estate planning result" in every case, whatever that looks like in each unique situation.

You’ve written extensively about the "psychology of estate planning." In your experience, what is the single biggest psychological hurdle for family business shareholders to begin estate planning?

Paul Hood: Perhaps the greatest hurdle to estate planning is most people lack sufficient self-awareness. By self-awareness, I mean that almost no one realizes the power that each of us has with respect to our estate planning decisions. One of my most important beliefs and philosophies about estate planning is that a person’s estate plan will have effects on the relationships of those who survive them, whether they want them to or not.

One of the reasons why I preach the gospel of intergenerational communication from every pulpit that’ll have me is because the best estate plans I’ve ever witnessed all involved honest two-way communication between givers and receivers. Perhaps the biggest reason for post-death estate or trust litigation is the parties didn’t communicate about the estate plan.

After the testator’s death, if an heir is unhappy about the estate plan, they too often entertain what I call the parade of horribles because what happened didn’t meet their expectations, and they immediately too often blame someone still alive and come out suing.

A simple explanation of why the testator arranged their estate plan the way they did can eliminate a lot of post-death litigation and hurt feelings and ended relationships. A simple conversation could cut off heartbreak and family cutoff, yet most estate planners don’t implore their clients to have these essential conversations.

Estate planning tends to focus primarily on minimizing transfer taxes. While that is a laudable goal, what other objectives should family business shareholders think about when it comes to estate planning?

Paul Hood: A "good estate planning result" is one in which property is properly transmitted as desired, and family relations among the survivors aren’t harmed during the estate-planning and administration process.

Notice that conspicuously absent from this definition is any mention of taxes. Taxes have always been the easiest piece of the estate-planning puzzle, yet the overwhelming majority of estate planners still focus their attention almost solely on the tax piece, probably because it’s easiest to solve and easiest to demonstrate quantifiable, tangible results. This misfocus has contributed to several problems for planners and clients alike.

The sad fact is that perfectly confected and properly drafted estate plans render families asunder every single day in this country because the estate planners failed to address the human side of estate planning. Sadly, many of these problems are easily predictable. Frankly, I don’t know how some estate planners sleep at night.

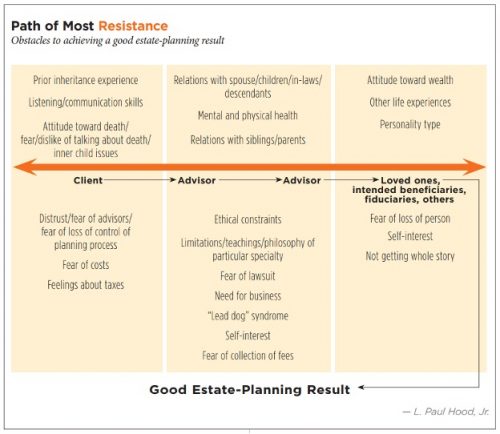

In one of your articles, you describe a "Path of Most Resistance" to achieving a good estate-planning results. Once a family business shareholder decides to engage in estate planning, what are the pitfalls that they need to watch out for?

Paul Hood: The Path of Most Resistance is a model that I developed to illustrate graphically what has to happen in order to achieve the "good estate planning result" that I defined earlier.

As the Path model illustrates, there are psychological machinations at work in every participant in the estate planning play, which includes the estate planners. As I have already discussed, intergenerational communication is essential in my opinion, particularly in a family business.

Where there’s a family business involved, I view a frank and honest keep-or-sell discussion involving the entire family as perhaps the most important conversation that too few families in business ever have. Why is that? I view such a discussion as a means of gauging the family members’ individual and collective interests in continuing to be in business together. However, it’s a loaded question that can open up some family wounds, so caution is in order.

Done correctly, the discussion can reinvigorate a business family’s overt commitment to the business in its current form. Unfortunately, lots can go wrong and can hasten or cause loss of the family business and family relationships because the keep or sell discussion can get very emotional and bring out hidden or suppressed feelings that have been harbored in silence and allowed to simmer past the boiling point upon their invitation to the surface.

An estate plan should provide a system of checks and balances on power and authority, particularly in a family business. Estate planning necessarily involves a passing of the torch of leadership and control. As Lord Acton observed long ago, power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.

Power shifts can expose people and leave them vulnerable to oppression, even to being terminated in employment or as a beneficiary through, for example, a spiteful exercise of a power of appointment (POA). The purposeful estate planner will build in a series of checks and balances that simultaneously allow exercise of authority and provide protection to those who are subject to that authority, which can be in the form of veto powers, powers to remove and replace trustees, co-sale or tag along rights, accounting rights or similar types of protections.

As the Path model illustrates, there are psychological machinations at work in every participant in the estate planning play, which includes the estate planners. As I have already discussed, intergenerational communication is essential in my opinion, particularly in a family business.

Where there’s a family business involved, I view a frank and honest keep-or-sell discussion involving the entire family as perhaps the most important conversation that too few families in business ever have. Why is that? I view such a discussion as a means of gauging the family members’ individual and collective interests in continuing to be in business together. However, it’s a loaded question that can open up some family wounds, so caution is in order.

Done correctly, the discussion can reinvigorate a business family’s overt commitment to the business in its current form. Unfortunately, lots can go wrong and can hasten or cause loss of the family business and family relationships because the keep or sell discussion can get very emotional and bring out hidden or suppressed feelings that have been harbored in silence and allowed to simmer past the boiling point upon their invitation to the surface.

An estate plan should provide a system of checks and balances on power and authority, particularly in a family business. Estate planning necessarily involves a passing of the torch of leadership and control. As Lord Acton observed long ago, power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.

Power shifts can expose people and leave them vulnerable to oppression, even to being terminated in employment or as a beneficiary through, for example, a spiteful exercise of a power of appointment (POA). The purposeful estate planner will build in a series of checks and balances that simultaneously allow exercise of authority and provide protection to those who are subject to that authority, which can be in the form of veto powers, powers to remove and replace trustees, co-sale or tag along rights, accounting rights or similar types of protections.

Who are the different parties involved in the estate planning process? Do you have any tips for ensuring that all these parties work together for a successful outcome?

Paul Hood: As the Path model illustrates, there are several "players" in the estate-planning play. I realize that most clients have more than two estate-planning professionals or advisors assisting them, but the larger point is that having more than one advisor itself creates potential obstacles in the path toward a good estate-planning result.

In addition to the interested parties (the giver and one or more receivers), achieving a good estate planning outcome often involves one or more attorneys, an accountant, a valuation professional. Depending on the structure of the plan and the clients' needs, life insurance or other professionals may be involved in the process as well.

The client should have as many advisors as he feels is necessary or appropriate. I’m a big believer in referrals and collaboration simply because it was my experience that clients get better service and a better estate plan. However, having more advisors creates a situation that must be watched and managed. I’ve seen estate-planning engagements fall apart because the advisors were incapable of cooperating and collaborating, which is a bad result for the client and can add to the negative experiences that the client will take to the next advisor, if any.

Each of the estate-planning sub- specialties have their own ethical rules and conventions. These ethics rules impact subspecialties differently. The legal ethics rules insert some additional complexities in the estate-planning process, particularly in the areas of confidentiality and conflicts of interest. It’s imperative that the planner’s engagement letter permits complete and total access to all of a client’s advisors.

Moreover, different advisors in the same subspecialty may have vastly different philosophies about estate planning. It’s critical that advisors check their egos and biases at the door before getting down to work with an open mind and collaboratively on a client’s situation. With collaboration comes diversity of professional backgrounds, educational and experiential pedigrees; different manners of training; and significant knowledge about a certain aspect of the client’s estate plan. This diverse strength of the group exceeds the strength of the sum of its individual members. This excess is called synergy.

Estate planning is one of the most important tasks a business owner will face. Assembling the right team, and making sure they can work together, can increase the odds that you achieve a good estate planning result.