2024: Five Trends to Watch in the Medical Device Industry

Medical Devices Overview

The medical device manufacturing industry produces equipment designed to diagnose and treat patients within global healthcare systems. Medical devices range from simple tongue depressors and bandages to complex programmable pacemakers and sophisticated imaging systems. Major product categories include surgical implants and instruments, medical supplies, electro-medical equipment, in-vitro diagnostic equipment and reagents, irradiation apparatuses, and dental goods.

The following outlines five structural factors and trends that influence demand and supply of medical devices and related procedures.

1. Demographics

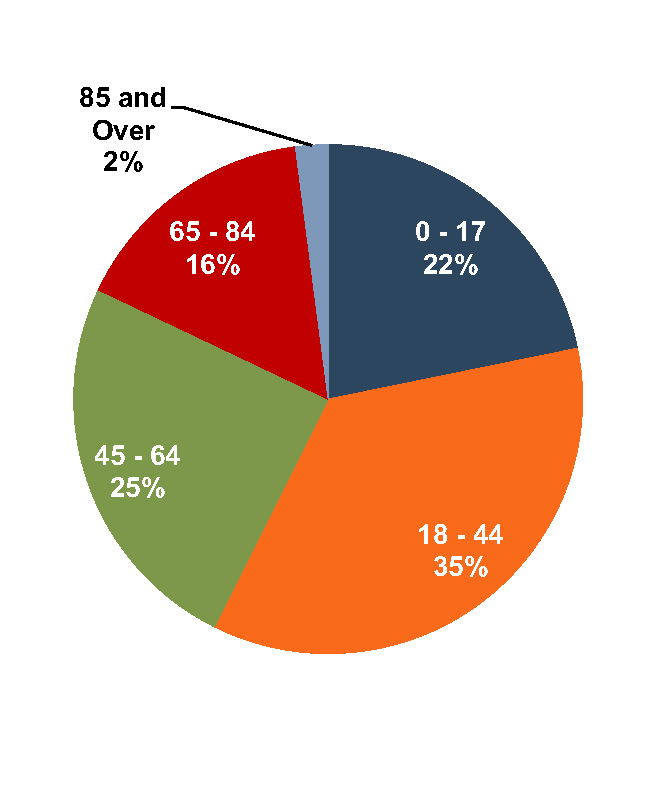

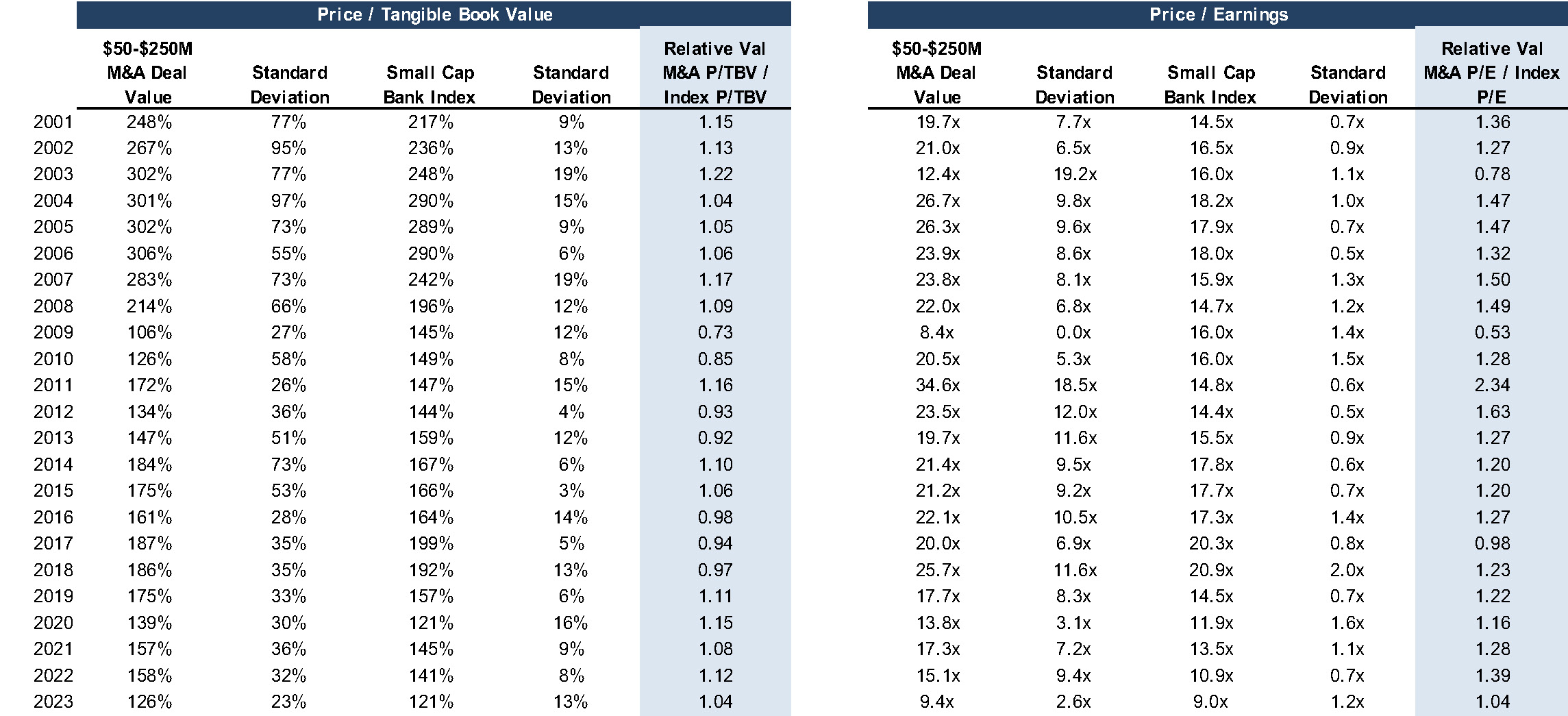

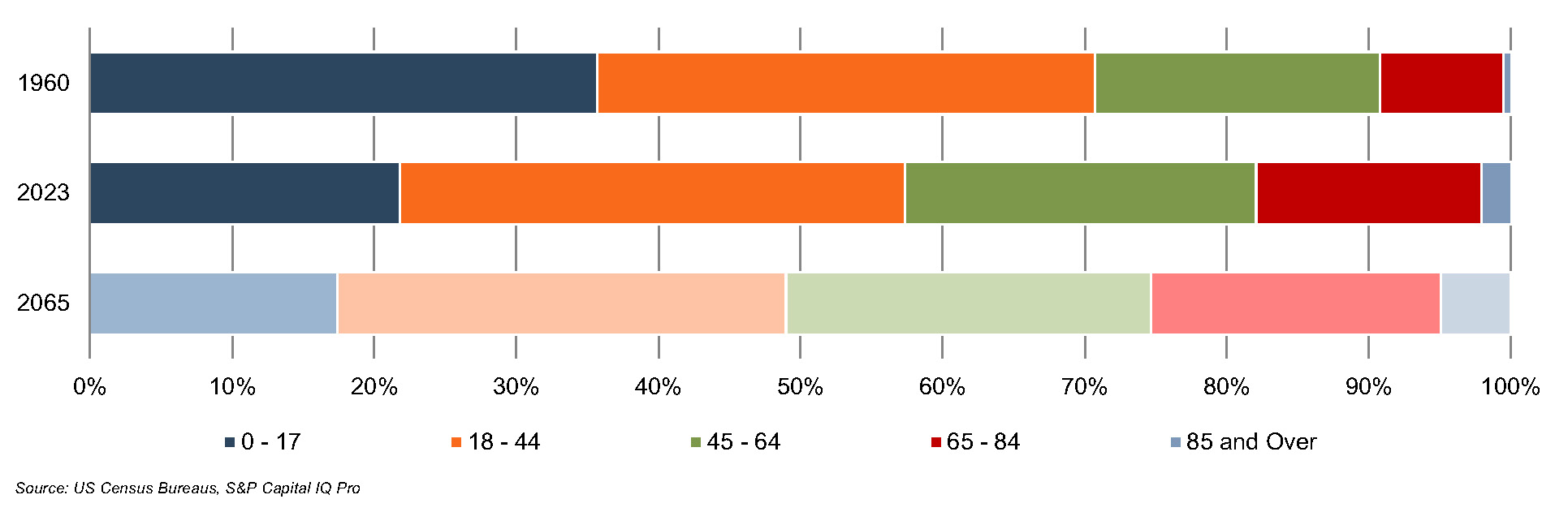

The aging population, driven by declining fertility rates and increasing life expectancy, represents a major demand driver for medical devices. The U.S. elderly population (persons aged 65 and above) totaled 60 million in 2023 (18% of the population). The U.S. Census Bureau estimates that the elderly will number 92.7 million by 2065, representing more than 25% of the total population.

U.S. Population Distribution by Age Group

The elderly account for nearly one third of total. Personal healthcare spending for the population segment was approximately $22,000 per person in 2020, 5.5 times the spending per child (about $4,000) and more than double the spending per working-age person (about $9,000).

U.S. Population Distribution by Age

U.S. Healthcare Expenditure by Age

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Office of the Actuary, National Health Statistics Group

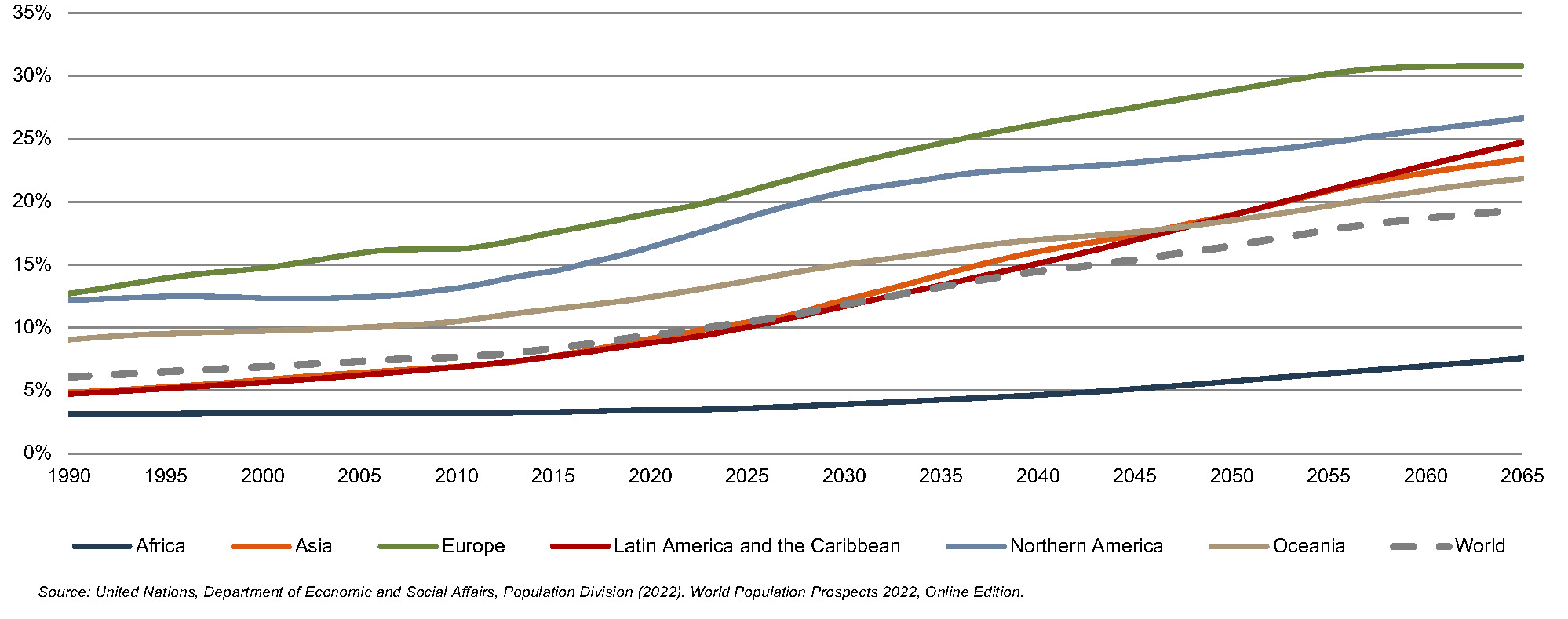

According to United Nations projections, the global elderly population will rise from approximately 808 million (10% of world population) in 2022 to 2.0 billion (19.4% of world population) in 2065. Europe’s elderly made up 20% of the total population in 2022, and the proportion is projected to reach 31% by 2065, making it the world’s oldest region. Latin American and the Caribbean is currently one of the youngest regions in the world, with its elderly at 9% of the total population in 2022, but this region is expected to undergo drastic transformations over the next several decades, with the elderly population expected to expand to 25% of the total population by 2065. North America has an above-average elderly population as of 2022 (17%) and is projected to expand to 27% by 2065.

World Population 65 and Over (% of Total)

Click here to expand the image above

2. Healthcare Spending and the Legislative Landscape in the U.S.

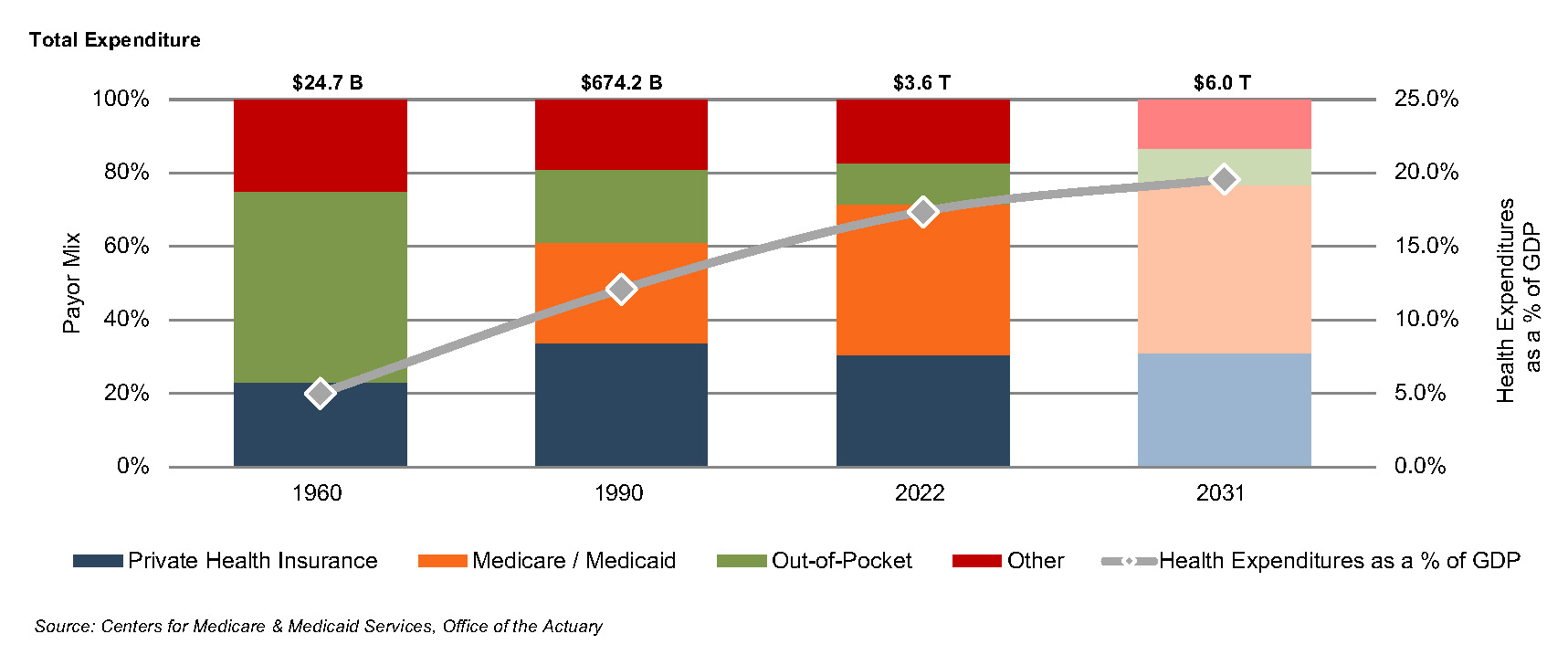

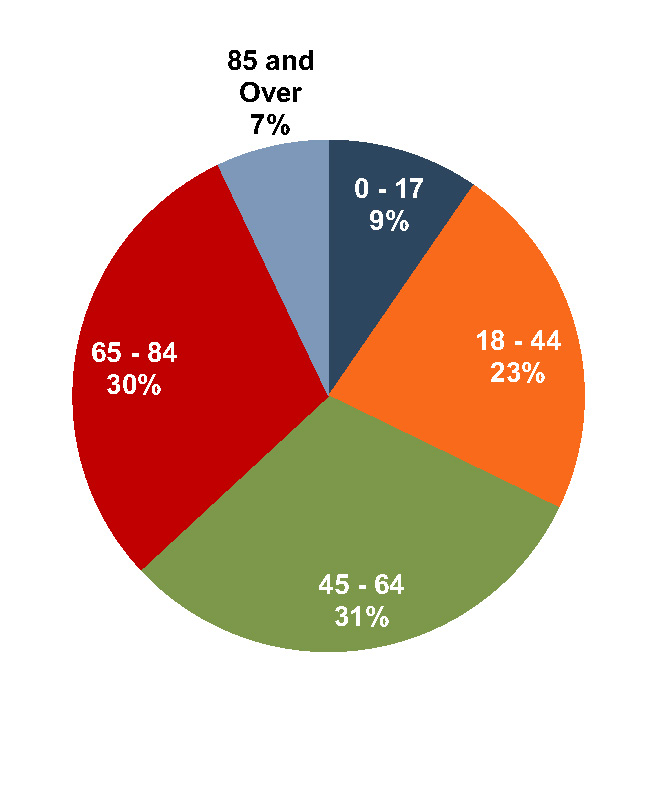

Demographic shifts underlie the expected growth in total U.S. healthcare expenditure from $4.4 trillion in 2022 to $7.2 trillion in 2031, an average annual growth rate of 5.5%. This projected average annual growth rate is slightly higher than the observed rate of 5.1% between 2013 and 2021, suggesting some acceleration in expected spending. Projected growth in annual spending for Medicare (7.5%) and Medicaid (5.0%) is expected to contribute substantially to the increase in national health expenditure over the coming decade. Growth in national healthcare spending, after significant growth in 2020 of 10.2%, slowed to 2.7% in 2021. Healthcare spending as a percentage of GDP is expected to increase from 18.3% in 2021 to 19.6% by 2031.

Since inception, Medicare has accounted for an increasing proportion of total U.S. healthcare expenditures. Medicare currently provides healthcare benefits for an estimated 65 million elderly and disabled people, constituting approximately 10% of the federal budget in 2021. Spending growth is expected to average 7.8% from 2025 to 2031. The program represents the largest portion of total healthcare costs, constituting 21% of total health spending in 2021 and 10% of the federal budget. Medicare accounts for 26% of spending on hospital care, 26% of physician and clinical services, and 32% of retail prescription drugs sales.

U.S. Healthcare Consumption Payor Mix and as % of GDP

Average Spending Growth Rates, Medicare and Private Health Insurance

Due to the growing influence of Medicare in aggregate healthcare consumption, legislative developments can have a potentially outsized effect on the demand and pricing for medical products and services. Medicare spending totaled $944.3 billion in 2022 and is expected to reach $1.8 trillion by 2031.

The Inflation Reduction Act (“IRA”) was signed into law on August 16, 2022 by the Biden administration. Among other items, the IRA aims to lower prescription drug costs and improve access to prescription drugs for Medicare enrollees. Two healthcare spending-related items in the IRA include out-of-pocket caps for insulin products (capped at $35 for each monthly subscription under Part D and Part B) and a $2,000 out-of-pocket annual spending cap for drugs under Medicare Part D. These provisions could have significant effects on the growth rates for out-of-pocket spending for prescription drugs, which are projected to decline by 5.9% and 4.2% in 2024 and 2025, respectively.

3. Third-Party Coverage and Reimbursement

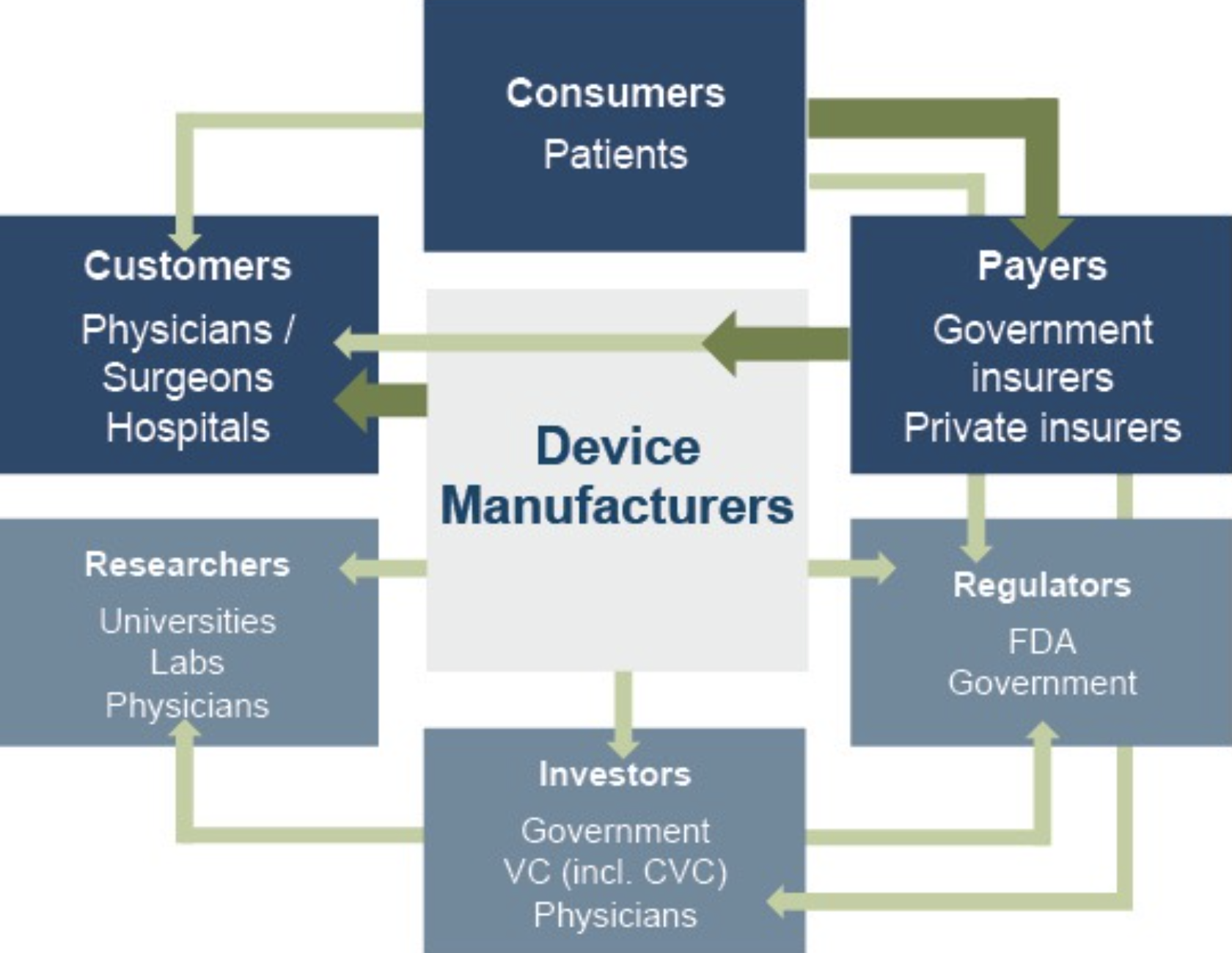

The primary customers of medical device companies are physicians (and/or product approval committees at their hospitals), who select the appropriate equipment for consumers (patients). In most developed economies, the consumers themselves are one step (or more) removed from interactions with manufacturers, and, therefore, pricing of medical devices. Device manufacturers ultimately receive payments from insurers, who usually reimburse healthcare providers for routine procedures (rather than for specific components like the devices used). Accordingly, medical device purchasing decisions tend to be largely disconnected from price.

Third-party payors (both private and government programs) are keen to reevaluate their payment policies to constrain rising healthcare costs. Hospitals are the largest market for medical devices. Lower reimbursement growth will likely persuade hospitals to scrutinize medical purchases by adopting 1) higher standards to evaluate the benefits of new procedures and devices, and 2) a more disciplined price bargaining stance.

The transition of the healthcare delivery paradigm from fee-for-service (FFS) to value models is expected to lead to fewer hospital admissions and procedures, given the focus on cost-cutting and efficiency. In 2015, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) announced goals to have 85% and 90% of all Medicare payments tied to quality or value by 2016 and 2018, respectively, and 30% and 50% of total Medicare payments tied to alternative payment models (APM) by the end of 2016 and 2018, respectively. A report issued by the Health Care Payment Learning & Action Network (LAN), a public-private partnership launched in March 2015 by HHS, found that 48.9% of (traditional) Medicare payments were tied to Category 3 and 4 APMs in 2022, compared to 40% in 2021 and 35.8% in 2018.

In 2020, CMS released guidance for states on how to advance value-based care across their healthcare systems, emphasizing Medicaid populations, and to share pathways for adoption of such approaches. CMS states that value-based care advances health equity by putting focus on health outcomes of every person, encouraging health providers to screen for social needs, requiring health professionals to monitor and track outcomes across populations, and engaging with providers who have historically worked in underserved communities. Ultimately, lower reimbursement rates and reduced procedure volume will likely limit pricing gains for medical devices and equipment.

The medical device industry faces similar reimbursement issues globally, as the EU and other jurisdictions face similar increasing healthcare costs. A number of countries have instituted price ceilings on certain medical procedures, which could deflate the reimbursement rates of third-party payors, forcing down product prices. Industry participants are required to report manufacturing costs, and medical device reimbursement rates are set potentially below those figures in certain major markets like Germany, France, Japan, Taiwan, Korea, China, and Brazil. Whether third-party payors consider certain devices medically reasonable or necessary for operations presents a hurdle that device makers and manufacturers must overcome in bringing their devices to market.

4. Competitive Factors and Regulatory Regime

Historically, much of the growth of medical technology companies has been predicated on continual product innovations that make devices easier for doctors to use and improve health outcomes for the patients. Successful product development usually requires significant R&D outlays and a measure of luck. If viable, new devices can elevate average selling prices, market penetration, and market share.

Government regulations curb competition in two ways to foster an environment where firms may realize an acceptable level of returns on their R&D investments. First, firms that are first to the market with a new product can benefit from patents and intellectual property protection giving them a competitive advantage for a finite period. Second, regulations govern medical device design and development, preclinical and clinical testing, premarket clearance or approval, registration and listing, manufacturing, labeling, storage, advertising and promotions, sales and distribution, export and import, and post market surveillance.

Regulatory Overview in the U.S.

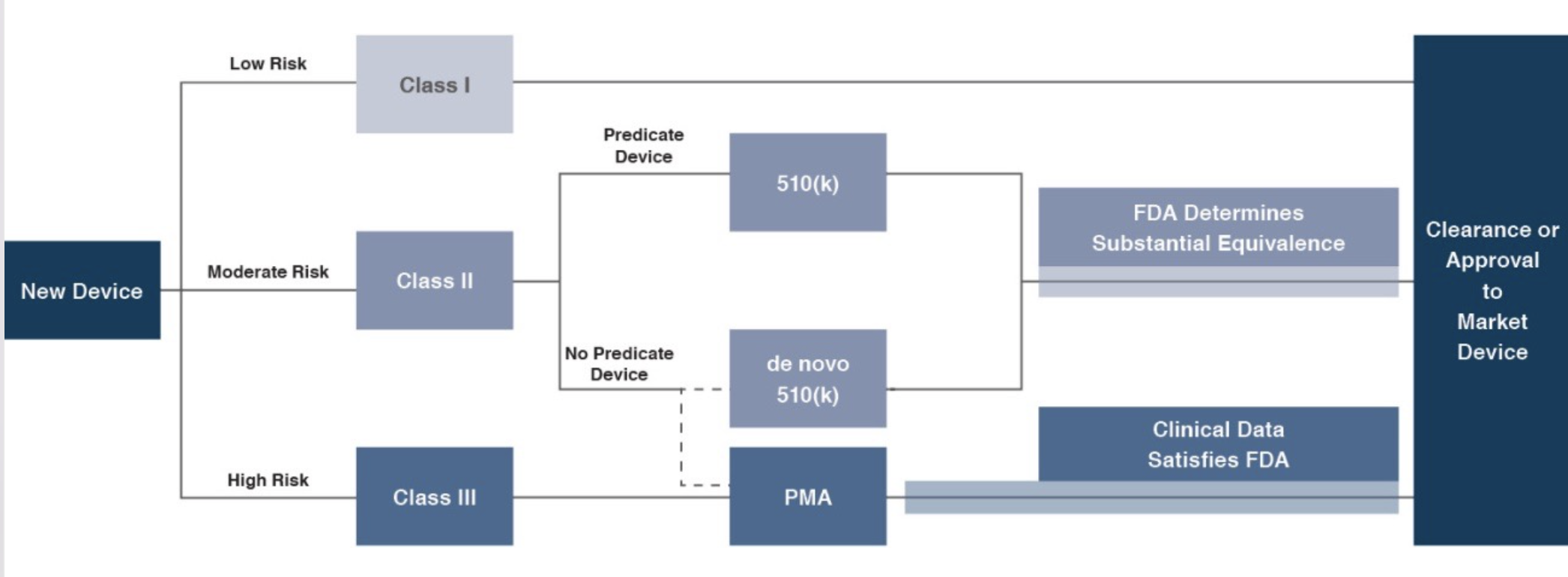

In the U.S., the FDA generally oversees the implementation of the second set of regulations. Some relatively simple devices deemed to pose low risk are exempt from the FDA’s clearance requirement and can be marketed in the U.S. without prior authorization. For the remaining devices, commercial distribution requires marketing authorization from the FDA, which comes in primarily two flavors.

- The premarket notification (“510(k) clearance”) process requires the manufacturer to demonstrate that a device is “substantially equivalent” to an existing device (“predicate device”) that is legally marketed in the U.S. The 510(k) clearance process may occasionally require clinical data and generally takes between 90 days and one year for completion. In November 2018, the FDA announced plans to change elements of the 510(k) clearance process. Specifically, the FDA plan includes measures to encourage device manufacturers to use predicate devices that have been on the market for no more than 10 years. In early 2019, the FDA announced an alternative 510(k) program to allow medical devices an easier approval process for manufacturers of certain “well-understood device types” to demonstrate substantial equivalence through objective safety and performance criteria. In February 2020, the FDA launched its voluntary pilot program: electronic Submission Template and Resource (eSTAR) as an interactive submission template that may be used by the medical device submitters to prepare certain pre-market submissions for a device. Starting in October 2023, all 510(k) submissions were required to be submitted using eSTAR unless exempted.

- The premarket approval (“PMA”) process is more stringent, time-consuming, and expensive. A PMA application must be supported by valid scientific evidence, which typically entails collection of extensive technical, preclinical, clinical, and manufacturing data. Once the PMA is submitted and found to be complete, the FDA begins an in-depth review, which is required by statute to take no longer than 180 days. However, the process typically takes significantly longer and may require several years to complete.

Pursuant to the Medical Device User Fee Modernization Act (MDUFA), the FDA collects user fees for the review of devices for marketing clearance or approval. The current iteration of the Medical Device User Fee Act (MDUFA V) came into effect in October 2022. Under MDUFA V, the FDA is authorized to collect $1.8 billion in user fee revenue for the five-year cycle, an increase from the approximately $1 billion in user fees under MDUFA IV, between 2017 and 2022. A significant change from MDUFA IV to MDUFA V relates to performance goals for De Novo Classification requests (requests for novel medical devices for which general controls alone provide reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness for the intended use). There has also been updated PMA guidance, with the FDA conducting substantive reviews within 90 calendar days for all original PMAs, panel-track supplements, and 180-day supplements.

Regulatory Overview Outside the U.S.

The European Union (EU), along with countries such as Japan, Canada, and Australia all operate strict regulatory regimes similar to that of the FDA, and international consensus is moving towards more stringent regulations. Stricter regulations for new devices may slow release dates and may negatively affect companies within the industry.

Medical device manufacturers face a single regulatory body across the European Union: Regulation (EU 2017/745), also known as the European Union Medical Device Regulation (EU MDR). The regulation was published in 2017, replacing the medical device directives regulation that was in place since the 1990s. The requirements of the MDR became applicable to all medical devices sold in the EU as of May 26, 2021. The EU is the second largest market for medical devices in the world with approximately €150 billion in sales in 2022, only behind the United States. The EU MDR has introduced stricter requirements for medical device manufacturers, including increased clinical evidence and post-market surveillance. Consequently, there is an increased risk for longer approval processes and delays in manufacturing of these devices.

5. Emerging Global Markets

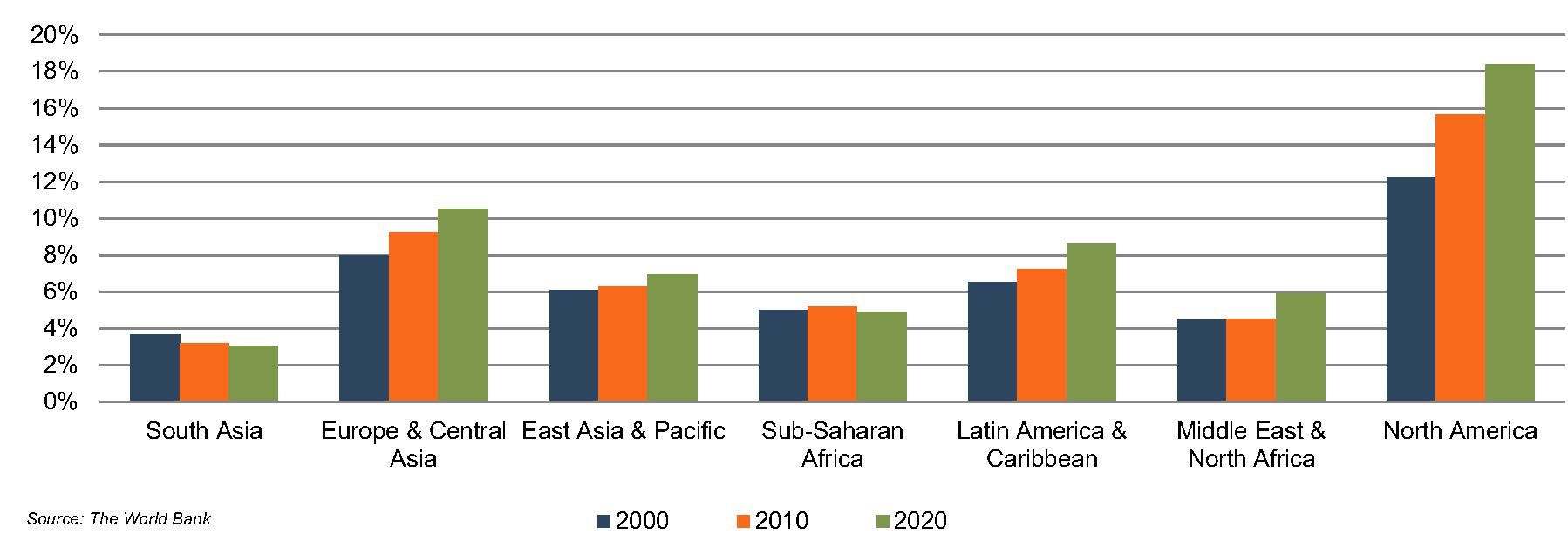

Emerging economies are claiming a growing share of global healthcare consumption, including medical devices and related procedures, owing to relative economic prosperity, growing medical awareness, and increasing (and increasingly aging) populations. According to the WHO, middle income countries, such as China, Turkey, and Peru, among others, are rapidly converging towards outsized levels of spending as their income scales. When countries grow richer, the demand for health care increases along with people’s expectation for government-financed healthcare. Upper-middle income countries accounted for 16.6% of total global healthcare spending in 2021, up from 8.2% in 2000.

As global health expenditure continues to increase, sales to countries outside the U.S. represent a potential avenue for growth for domestic medical device companies. According to the World Bank, all regions (except Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia) have seen an increase in healthcare spending as a percentage of total output over the last two decades.

World Health Expenditure as a % of GDP

Global medical device sales are estimated to increase 5.9% annually from 2023 to 2030, reaching nearly $800 billion according to data from Fortune Business Insights. While the Americas are projected to remain the world’s largest medical device market, the Asia Pacific market is expected to expand at a relatively quicker pace over the next several years.

Summary

Demographic shifts underlie the long-term market opportunity for medical device manufacturers. While efforts to control costs on the part of the government insurer in the U.S. may limit future pricing growth for incumbent products, a growing global market provides domestic device manufacturers with an opportunity to broaden and diversify their geographic revenue base. Developing new products and procedures is risky and usually more resource intensive compared to some other growth sectors of the economy. However, barriers to entry in the form of existing regulations provide a measure of relief from competition, especially for newly developed products.

Post-Script – 2024 Outlook

The medical device industry looked to have put the effects of COVID-19 behind by 2023. A large number of elective procedures were deferred in the early part of the pandemic and a measure of catch-up in procedure volumes was reported in subsequent periods. Back to focusing on the longer-term demographic and other trends?

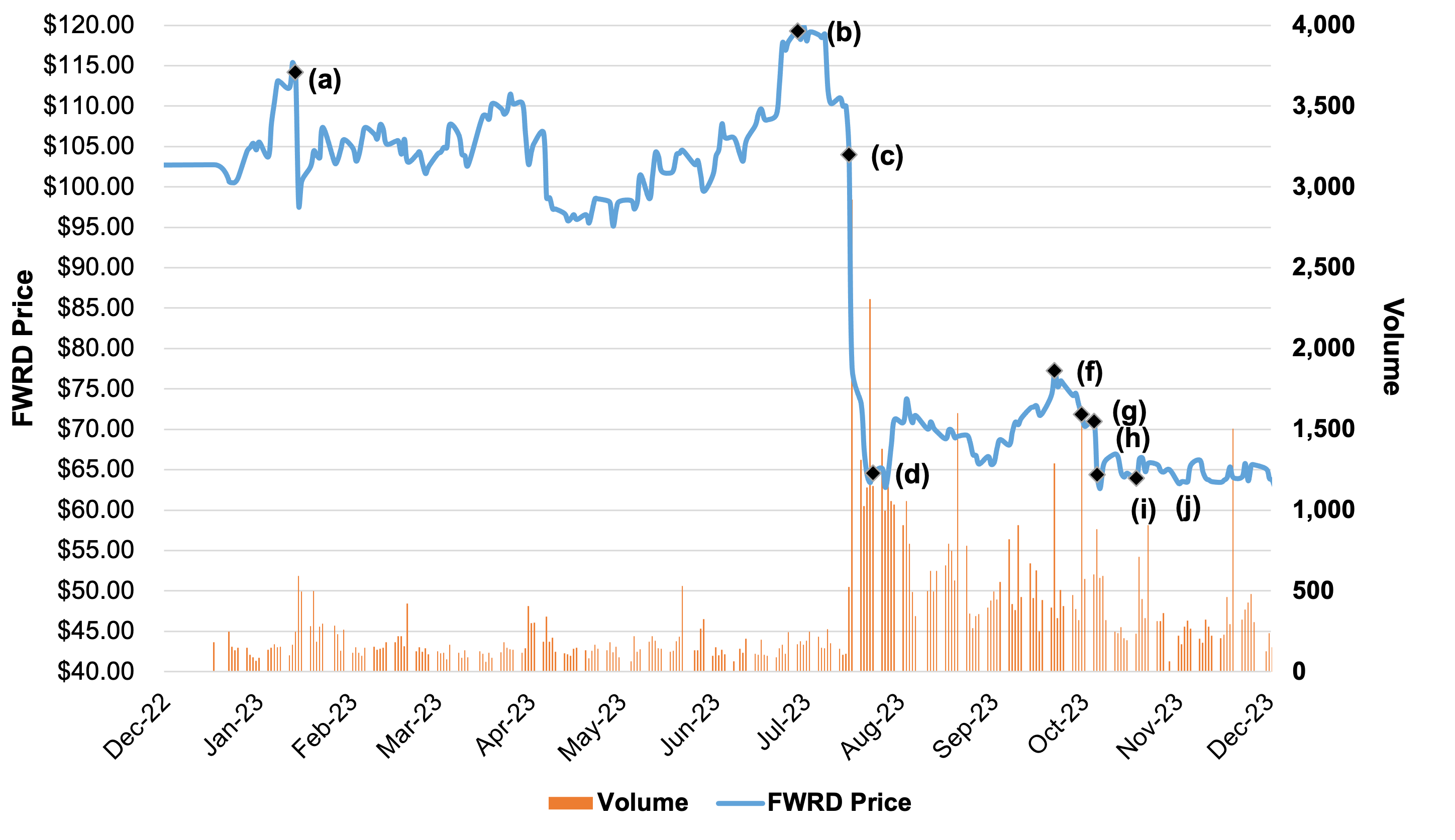

Well, maybe not quite so fast. It was always likely that the pandemic-induced disruptions would linger just a bit longer, creating some uncertainty around consumers’ needs and preferences. But the industry awakened to a different type of potential disruption in mid-2023. Would GLP-1 drugs alter long-term demographic trends by reducing massive obesity rates? And would the industry face widespread lower demand for bariatric surgery devices, glucose monitors, cardiovascular devices, orthopedic implants and other equiptment? A mid-year swoon in medtech stock prices was attributed, at least by some, to the wonder drugs. As 2023 came to a close, however, many appear to have reversed course from that early response. We may or may not get more clarity on the longer-term effects of these treatments in 2024 but, surely, they will also bring opportunities to go along with potential challenges for device makers.

Taking a broader view, some trends from recent periods will likely persist in 2024. Companies will continue to focus on profitability and profitable growth in a (relatively) higher-interest rate environment. Some observers suggest that an expected but measured decline in rates over 2024 (if it materializes) may not do much for medtech stock prices, further underscoring the need to shore up margins. On the flip side, since the period of rapid interest rate increases appears to be behind us, transaction volume should pick up from the low levels of the past two years. Finally, innovation, as always, will continue to be part of the conversation as novel treatments that serve unmet needs will help to unlock new markets.

2024 Outlook reading list:

- What To Expect From Medtech In 2024 (McKinsey & Company)

- 5 Medtech Trends To Watch In 2024 (MedtechDive)

- 2024 Outlook For Life Sciences: GenAI, Drug Prices, Economy Likely To Influence Strategy (Deloitte)

NYCB Incurs Heavy Dilution in Its $1.0 Billion Capital Raise

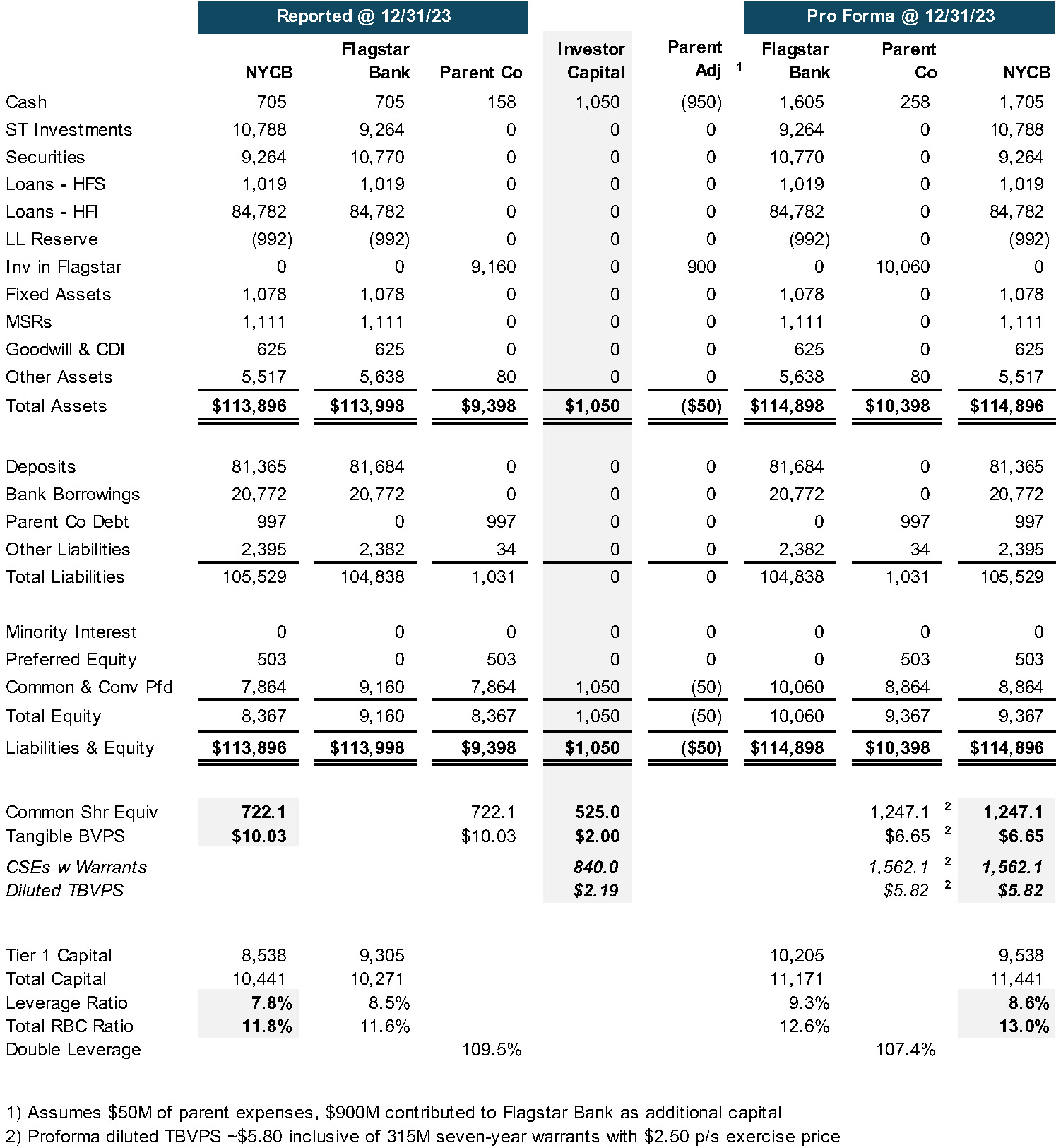

The other significant industry news from the first quarter was the $1.05 billion equity investment in New York Community Bank (NYSE: NYCB) by an investor group led by former Secretary of the Treasury Steve Mnuchin. The investment was necessary to boost loss absorbing capital and to shore up confidence to stem a possible deposit run after its share price collapsed during February following a surprise fourth quarter loss that was later revised higher for a $2.4 billion goodwill write-off.

The initially reported 4Q23 loss of $252 million was not catastrophic, especially considering the company reported net income of $2.4 billion excluding the goodwill write-off as a result of the bargain gain from the purchase of the failed Signature Bank; however, the fourth quarter loss that arose from a $538 million provision for loan losses highlighted investor concerns about NYCB’s sizable exposure to NYC rent-controlled apartments and offices.

The figure on the right presents our proforma analysis of the transaction and its impact on the consolidated company (NYCB), the parent company in which the group invested, and wholly owned Flagstar Bank, N.A. The adage that capital is exorbitantly expensive if available at all when it must be raised comes to mind here with NYCB.

Source: Mercer Capital, NYCB SEC filings, and S&P Global Market Intelligence

We note the following:

- The investor group paid $1.05 billion for 525 million common share equivalents consisting of 59.8 million common shares for $2.00 per share and $930 million of Series B and C preferred stock with a 13% dividend that is convertible into 465 million common shares at $2.00 per share.

- Tangible book value per share (“TBVPS”) declined by about one-third from $10.03 per share as of year-end 2023 to $6.65 per share on a proforma basis.

- Inclusive of 315 million seven-year warrants with a $2.50 per share strike price, diluted proforma TBVPS is ~$5.80 per share.

- The 525 million common shares represent ~40% of the 1.25 billion proforma shares while dilution to existing shareholders exceeds 50% inclusive of the warrants.

- The capital injection boosted the Company’s consolidated leverage ratio by ~80bps to 8.6% and total risk-based capital ratio by ~120bps to 13.0%.

- NYCB will generate ~$1.4 billion of pretax, pre-provision operating income in 2024 and 2025 based upon consensus analyst estimates that will supplement the new capital to absorb loan losses.

- Given NYCB’s shares are trading around 50% to 60% of proforma TBVPS, investors are questioning the magnitude of loan losses to be recognized; whether more capital will be required; and long-term earning power.

Our additional thoughts on the transaction can be found HERE, and a link to NYCB’s investor deck announcing the transaction can be found HERE.

If we can assist your board with a capital raise or other significant transaction, please call us.

Capital One Financial Corporation to Acquire Discover Financial Services

The four major credit card networks are American Express, Discover, Mastercard, and Visa. In 2023, Discover had only 2.1% of the total market share in the U.S. based on the value of transactions, compared to Visa’s 61.1% market share and Mastercard’s 25.4% market share.1 Prior to its acquisition of Discover, Capital One partnered with both Visa and Mastercard for issuing their credit cards. So, why would Capital One pay $35.3 billion to acquire Discover’s 2.1% market share?

Discover Financial Services operates as both a credit card issuer and credit card network. By owning its own credit card network, Discover is not partnered with any payment processors (Visa, Mastercard, etc.) and avoids “swipe fees” that payment processors collect. Therefore, one of Capital One’s primary objectives in acquiring Discover is to move its credit and debit cards onto Discover’s network over time and reduce its purchase volume on the Visa and Mastercard networks.

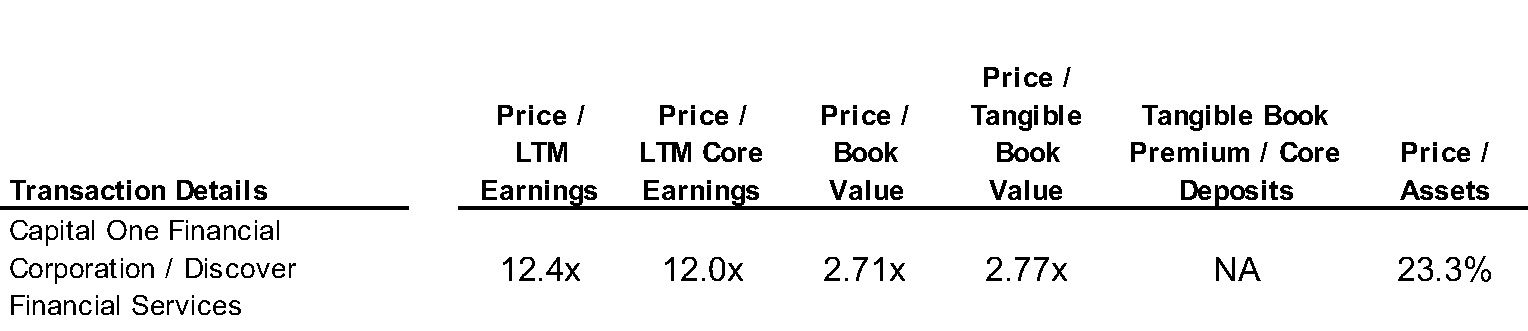

The two companies entered into a definitive agreement on February 19, 2024, in which Capital One Financial Corporation agreed to acquire Discover Financial Services in an all-stock transaction valued at $35.3 billion. The deal represents a 26.6% premium to Discover’s closing price of $110.49 (2/26/24) as Discover shareholders will receive 1.0192 Capital One shares for each Discover share. More details on the transaction as well as the companies’ financials as of fiscal 2023 are displayed on the right.

Summary of Transaction Analysis

Financial Comparison

Preparing for the Future

As technology continues to advance, both traditional, tech-heavy banks and

Fintech companies have increased competition in the global payments industry. If the acquisition is approved, Capital One will surpass JPMorgan as the largest credit card company based on loan volume and become the third largest company based on purchase volume. With increased volume and market share, Capital One would be better prepared to compete against these other banks and Fintech companies. Richard Fairbank, the CEO of Capital One, strives to deal directly with merchants by owning his own payments network. This rare asset allows Capital One to create a closed loop between consumers and merchants, which better positions the company to deal with increasing threats from buy-now, pay-later companies (Affirm, Afterpay, Klarna, etc.).

Both Capital One and Discover customers may have a lot to look forward to in the future should the deal be approved. Capital One intends to move 25 million cardholders onto the Discover network by 2027 and offer more attractive rewards for both debit and credit cardholders. The proposed merger would expand both issuers’ physical presence, and Discover customers would gain access to physical bank locations. Capital One will also leverage its international presence to increase accessibility and convenience for Discover cardholders on an international scale. In terms of credit and debit rewards, the increased competition in the industry is expected to drive companies to bolster their rewards program to seem more attractive to consumers.

Regulatory Hurdles

The proposed deal between Capital One and Discover is expected to close by the end of 2024 or the beginning of 2025. However, the completion of the deal could depend on the results of the presidential election. Senators Elizabeth Warren and Josh Hawley have both expressed interest in blocking the deal as they believe the deal will create a “juggernaut” in the industry and lead to the extortion of American consumers. The Biden administration is more likely to block the deal or implement limitations and requirements in order for it to be executed.

On the other hand, the proposed deal could stop legislation that threatens credit card rewards. Congress is considering new legislation known as the Credit Card Competition Act (CCCA). The purpose of this legislation is to reduce the swipe fees paid by merchants by enabling access to a wider range of payment networks. If the legislation is approved, credit card networks and issuers would face reduced transaction fees causing issuers to potentially reduce the wide range of rewards offered. However, the primary objective of the CCCA could be accomplished through the proposed merger, as routing Capital One’s purchase volume through Discover’s payment network would create a more viable competitor to the Visa/Mastercard duopoly.

Conclusion

Mercer Capital has roughly 40 years of experience in assessing mergers, the investment merits of the buyer’s shares, and providing valuations of financial institutions. If you are considering acquisition opportunities or have questions regarding the valuation of your financial institution, please contact us.

1 Statista.com; Market share of Visa, Mastercard, American Express, Discover as general purpose card brands in the United States from 2007 to 2023, based on value of transactions

Potential Impact of Baltimore Bridge Collapse on the Logistics Industry

It’s been hard to miss the news footage and video of the cargo ship Dali colliding with the Francis Scott Key Bridge across the Chesapeake Bay. The bridge collapse – as sudden as it is surprising – is another landmark in what has been a series of tumultuous years in the logistics industry. We recently wrote about global impacts on the supply chain, particularly East Coast ports, and this is another reminder about how unpredictable events can have a wide reach.

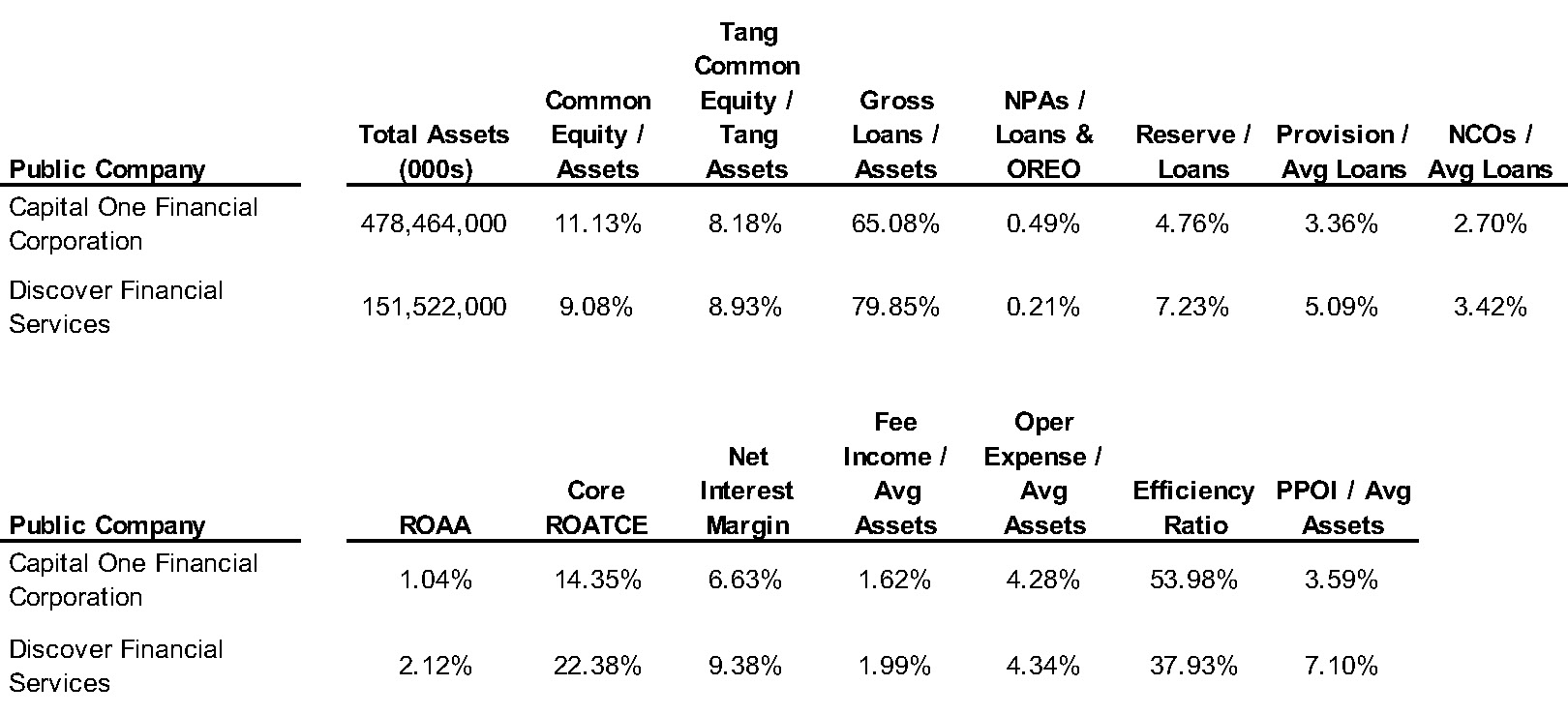

The Port of Baltimore

The Port of Baltimore is in the top twenty ports by volume in the United States and is the 5th largest port for foreign trade on the East Coast. The Washington Post estimates that the port handled over 50 million tons of foreign cargo with value in excess of $80 billion during 2023. The port is the 2nd largest exporter of coal from the U.S. (though still a relatively small player on a global scale) and is the largest port for imports of automobiles, sugar, and gypsum. Baltimore is also equipped to handle Neo Panamax ships passing through the Panama Canal.

Sharing the fortunes of several other East Coast ports of the last several years, the Port of Baltimore posted several records in 2023, including for the largest number of TEUs handled (1.1 million) and general cargo tons (11.7 million). Baltimore posts these growth records despite the overall decline in imports to the U.S. during 2022.

Potential Short-Term and Long-Term Impact

Short term impacts will include delays of cargo already in transit for East Coast ports, whether originally bound for Baltimore or not. Just as we saw chokepoints on the West Coast lead to a redistribution of cargo among ports, the loss of the Baltimore port for the foreseeable future will cause ripple effects throughout the industry.

Source: The Washington Post

Other East Coast ports will likely take up the bulk of cargo previously destined for Baltimore. In particular, soybean shipments are expected to transfer to Norfolk, Savannah, and Charleston, while containers are expected to be processed in either Philadelphia or Norfolk. In any case, the truck routes and rail cars that previously serviced Baltimore will need to be recentered on other ports.

However, this will be somewhat mitigated by global events that were already impacting East Coast ports—namely, the ongoing drought limiting capacity through the Panama Canal and the Houthi rocket attacks in the Red Sea, both of which had diverted some cargo away from East Coast ports prior to the bridge collapse.

An additional concern is the International Longshoreman’s Association contract, which covers port workers from Texas through the Northeast. The contract is set to expire in September 2024. Talks stalled in early 2023 before resuming again in February 2024.

The West Coast freight bottleneck that dominated transportation headlines in 2022 was brought on by labor disputes combined with a drastic increase in demand for shipping services due to COVID-fueled shopping. Conversely, the national freight market has been soft through 2023 and demand is not expected to rapidly escalate as it did a few years ago. This should limit long-term bottlenecks and chokepoints from forming on the East Coast.

Conclusion

Mercer Capital’s Transportation & Logistics team constantly watches the transportation industry and global events and economic factors that can impact the overall industry, the supply chain, or various aspects of transportation.

Mercer Capital provides business valuation and financial advisory services, and our transportation and logistics team helps trucking companies, brokerages, freight forwarders, and other supply chain operators to understand the value of their business. Contact a member of the Mercer Capital transportation and logistics team today to learn more about the value of your logistics company.

Essential Financial Documents to Gather During Divorce – Part 2

Documents Needed to Analyze Support and Need (A Lifestyle Analysis)

Prepared by Mercer Capital’s Family Law Services Team

In Part 1 of this series, we discussed the importance of hiring an expert and the documents needed to prepare the marital balance sheet including tax returns and a personal financial statement.

In this article, we discuss the documents needed for analyzing support and need, otherwise known as a Lifestyle Analysis or a Pay and Need Analysis.

Analyzing what would be a reasonable amount for alimony is based upon both a division of assets as of the divorce date (covered in Part 1 of this series) and expectations for future income and expense. We frequently perform a Lifestyle Analysis for divorcing parties. This analysis examines and documents each party’s sources of income and expenses. As noted in our article on Lifestyle Analysis, it is used in the divorce process to demonstrate the standard of living during the marriage and to determine the living expenses and spending habits of each spouse. It is typically a more in-depth analysis required in the divorce process and is prepared by an expert credentialed in forensics.

As part of the divorce proceedings, each party typically files a financial affidavit, which is simply an expected monthly budget post-marriage. The historical status quo, or lifestyle, usually serves as a basis for developing these expenses. However, two households going forward sometimes cannot be similarly supported by the historical marital budget. For example, a married couple with a mortgage provides shelter for both spouses whereas post-divorce, there will be an additional mortgage or rent expense. Sometimes the marital residence will be sold, and each party will live in accommodations more commensurate with what is affordable within the divorcing parties’ new budget.

Documents for Support Analysis or Alimony/Child Support (Comparing Marital Income vs. Budgeted Expenses)

While rent/mortgage is one of the largest monthly expenses, the financial affidavit will include a variety of categories including home, maintenance, vehicle, utilities, food costs, and other typical “fixed” or “shared” monthly expenses captured in a budget. Sometimes financial experts help with this process, while other times attorneys and clients gather and determine these budgets. Attorneys typically provide a template for monthly expenses, but clients may need to corroborate their entries with the following documents:

- Utility bills (cable, internet, electric, water, gas)

- Insurance (health, life, etc.) premiums

- Mortgage statement (“PITI” – which stands for principal, interest (both from fixed monthly mortgage payment), taxes and insurance)

- Credit card statements which may further break down:

- Groceries

- Gas

- Subscriptions (Netflix, Amazon Prime, etc.)

- Travel

- Meals & Entertainment

- Health & Wellness

- Medical

- Etc.

It’s important to note that these expenses, where possible, should reflect those of the divorcing spouses, not child-related expenses. Child expenses such as tuition, extra curriculars, etc. should be considered separately in the award of child support paid to the primary care-taker and/or spouse with lower income potential depending on the facts and circumstances of the case.

While understanding a couple’s expenses is important to determining alimony, reasonable expectations for future income is also very important. For a couple with a simple W-2 job, this analysis may be more straightforward. Still, there are many instances where income fluctuates from year-to-year based on bonuses or company performance, requiring more analysis and more documentation than what is provided on a W-2, 1099, or tax return. Helpful documents for determining income include:

- Bi-weekly or monthly paystubs

- Payroll registers

- 401k/ESOP statements detailing annual contribution levels

- Owner draws

- Documentation about restricted stock units, phantom stock, stock options, and other equity instruments

- Incentive-based compensation agreements such as bonus agreements

- Employment history

- Employment contracts

- Non-compete agreements

As noted above, the goal of this analysis is to determine ongoing earnings capacity. If a divorcing party was recently promoted where his/her compensation structure either increased or was materially changed (i.e. equity vs. W-2), a simple average of historical compensation likely will not be sufficient.

In many divorce cases, one spouse has taken on the primary responsibility of raising children. Depending on the facts and circumstances, a vocational expert may be needed to opine on the potential earning power of that spouse based on their experience, qualifications, education, credentials, and other pertinent information. While a credentialed financial expert should be able to make a reasonable determination for someone currently in the workforce, a specialized vocational expert may be required for a spouse who has not recently worked. All else equal, a higher earnings capacity for that spouse tends to reduce the “need” in determining alimony, and it becomes a more contested area in the process, which leads to the potential use of a vocational expert.

Tip for business owners: It is important to understand how much the party’s income is from services performed in his/her capacity as an executive versus how much of the income is a return on the capital invested in the business. How this gets analyzed in a Pay and Need Analysis can become complicated and is a hotly debated topic. Triers of fact may disagree on whether valuing the business also inherently considers some of this income, known as the “double dip.” Because officer compensation can be a key discussion within the valuation of a business, we will cover it in greater detail in a future part of this series.

Conclusion

A financial expert can help focus the scope of a divorce case, saving time and money throughout the process, particularly if brought in early to the process with ample time to assist with the various stages of the case. We make our engagements as efficient as possible, in hopes of reducing the need to update our analysis, which can drag out the process and lead to higher costs for clients.

For more information or to discuss your matter with us, please don’t hesitate to contact us.

Essential Financial Documents to Gather During Divorce Series

5 Reasons Sellers Need a Quality of Earnings Report

M&A deal flow was sidelined for much of 2022 and 2023, but the economy’s soft landing, stabilizing interest rates, and pent-up M&A demand are expected to compel buyers and sellers to renew their efforts in 2024 and beyond.

As deal activity recovers, sellers need to be prepared to present their value proposition in a compelling manner. For many sellers, an independent Quality of Earnings (“QofE”) analysis and report are vital to advancing and defending their asset’s value in the marketplace. And it can be critical to the ensuing due diligence processes buyers apply to targets.

The scope of a QofE engagement can be tailored to the needs of the seller. Functionally, a QofE provider examines and assesses the relevant historical and prospective performance of a business. The process can encompass both the financial and operational attributes of the business.

In this article, we review five reasons sellers benefit from a QofE report when responding to an acquisition offer or preparing to take their businesses to market.

1. Maximize value by revealing adjusted and future sustainable profitability.

Sellers should leave no stone unturned when it comes to identifying the maximum achievable cash flow and profitability of their businesses. Every dollar affirmed brings value to sellers at the market multiple. Few investments yield as handsomely and as quickly as a thorough QofE report. A lack of preparation or confused responses to a buyer’s due diligence will assuredly compromise the outcome of a transaction. The QofE process includes examining the relevant historical period (say two or three years) to adjust for discretionary and non-recurring income and expense events, as well as depicting the future (pro forma) financial potential from the perspective of likely buyers. The QofE process addresses the questions of why, when, and how future cash flow can benefit sellers and buyers. Sellers need this vital information for clear decision-making, fostering transparency, and instilling trust and credibility with their prospective buyers.

2. Promote command and control of transaction negotiations and deal terms.

Sellers who understand their objective historical performance and future prospects are better prepared to communicate and achieve their expectations during the transaction process. A robust QofE analysis can filter out bottom-dwelling opportunists while establishing the readiness of the seller to engage in efficient, meaningful negotiations on pricing and terms with qualified buyers. After core pricing is determined, other features of the transaction, such as working capital, frameworks for roll-over ownership, thresholds for contingent consideration, and other important deal parameters, are established. These seemingly lower-priority details can have a meaningful effect on closing cash and escrow requirements. The QofE process assists sellers and their advisors in building the high road and keeping the deal within its guardrails.

3. Cover the bases for board members, owners, and the advisory team and optimize their ability to contribute to the best outcome.

The financial and fiduciary risk of being underinformed in the transaction process is difficult to overcome and can have real consequences. Businesses can be lovingly nurtured with operating excellence, sometimes over generations of ownership, only to suffer from a lack of preparation, underperformance from stakeholders who lack transactional expertise, and underrepresentation when it most matters. The QofE process is like training camp for athletes — it measures in realistic terms what the numbers and the key metrics are and helps sellers amplify strengths and mitigate weaknesses. Without proper preparation, sellers can falter when countering an offer, placing the optimal outcome at risk. In short, a QofE report helps position the seller’s board members, managers, and external advisors to achieve the best outcome for shareholders.

4. Financial statements and tax returns are insufficient for sophisticated buyers.

Time and timing matter. A QofE report improves the efficiency of the transaction process for buyers and sellers. It provides a transparent platform for defining and addressing significant reporting and compliance issues. There is no better way to build a data set for all advisors and prospective buyers than the process of a properly administered QofE engagement. This can be particularly important for sellers whose level of financial reporting has been lacking, changing, outmoded due to growth, or contains intricacies that are easily misunderstood.

For sellers content to work their own deals with their neighbors and friendly rivals, a QofE engagement can provide some of the disciplines and organization typically delivered by a side-side representative. While we hesitate to promote a DIY process in this increasingly complicated world, a QofE process can touch on many of the points that are required to negotiate a deal. Sellers who are busy running their businesses rarely have the turnkey skills to conduct an optimum exit process. A QofE engagement can be a powerful supporting tool.

5. In one form or another, buyers are going to conduct a QofE process – what about sellers?

Buyers are remarkably efficient at finding cracks in the financial facades of targets. Most QofE work is performed as part of the buy-side due diligence process and is often used by buyers to adjust their offering price (post-LOI) and design their terms. It is also used to facilitate their financing and satisfy the scrutiny of underlying financial and strategic investors. In the increasing arms race of the transaction environment, sellers need to equip themselves with a counteroffensive tool to stake their claim and defend their ground. If a buyer’s LOI is “non-binding” and subject to change upon the completion of due diligence, sellers need to equip themselves with information to advance and hold their position.

Conclusion

The stakes are high in the transaction arena. Whether embarking on a sale process or responding to an unsolicited inquiry, sellers have precious few opportunities to set the tone. A QofE process equips sellers with the confidence of understanding their own position while engaging the buy-side with awareness and transparency that promotes a more efficient negotiating process and the best opportunity for a favorable outcome. If you are considering a sale, give one of our senior professionals a call to discuss how our QofE team can help maximize your results.

WHITEPAPER

Quality of Earnings Analysis

For buyers and sellers, the stakes in a transaction are high. A QofE report is an essential step in getting the transaction right.

Worldwide Impacts on Marine Shipping – Q4 2023

We discussed reshoring and nearshoring trends a bit in the last Value Focus Transportation and Logistics newsletter. There’s been some developments on that front, especially as it relates to the ongoing battle between East Coast and West Coast ports.

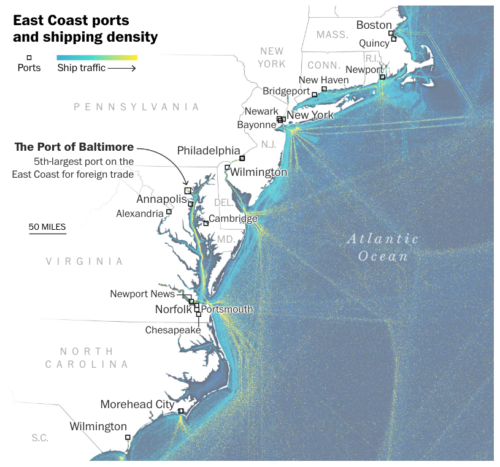

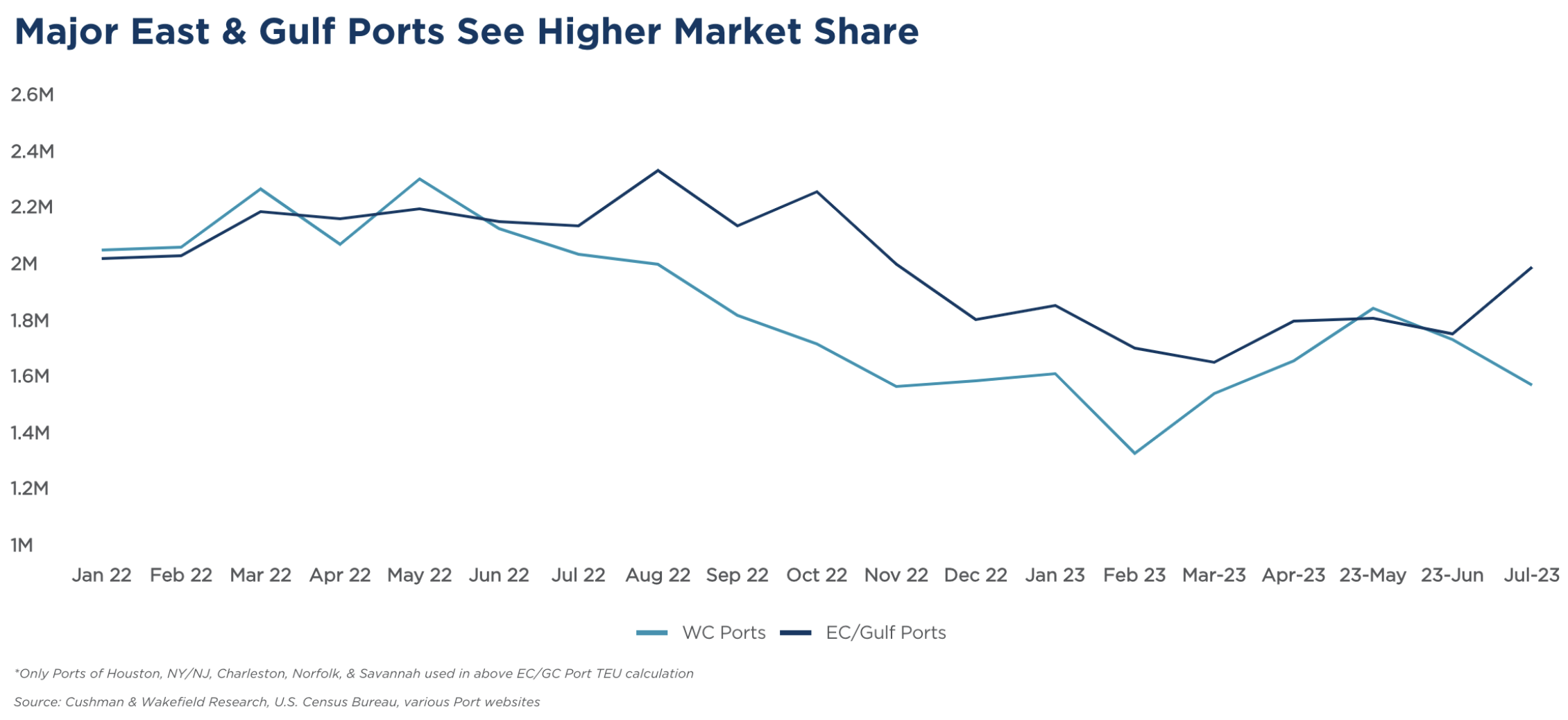

As we mentioned last time, a variety of pandemic-related and regulatory issues resulted in long delays at California ports, the traditional import location for the majority of goods from East Asia. Many carriers shifted their import handling to East Coast ports – with the port of Savannah being one of the biggest winners. Georgia has posted three straight record–setting years for exports. A study by Cushman Wakefield that ran through October 2023 shows that volumes at East Gulf Ports exceeded West Coast volumes for the majority of 2022 and 2023. However, early results indicate the West Coast ports grew faster than East Coast ports in November and December 2023, and there are a couple of reasons behind that.

(click here to expand the image above)

The El Niño weather event has hit the Panama Canal hard. Under normal conditions, between 36 and 38 ships per day will make the transit. Due to the worst drought Panama has experienced in over 70 years, the Canal Authority began reducing the number of ships passing through on a daily basis in July 2023. In February 2024, the Canal Authority reduced the total number of ships to 18 per day.

Meanwhile, approaching from the other direction has been made harder by attacks on vessels in the Red Sea. About one-fifth of freight reaching East Cost ports travels through the Red Sea and the Suez Canal. Shippers continuing to use the Suez canal route will face higher insurance charges, while shippers opting to go around the Cape of Good Hope can expect to add at least a week to transit times. More recently, the first fully sunk ship from the conflict also disrupted underwater data cables. So far, analysts have had mixed opinions on the overall impact that will arise from the Houthi attacks.

Between Red Sea disruptions and climate issues in Latin America the impact of worldwide current events on marine logistics cannot be ignored.

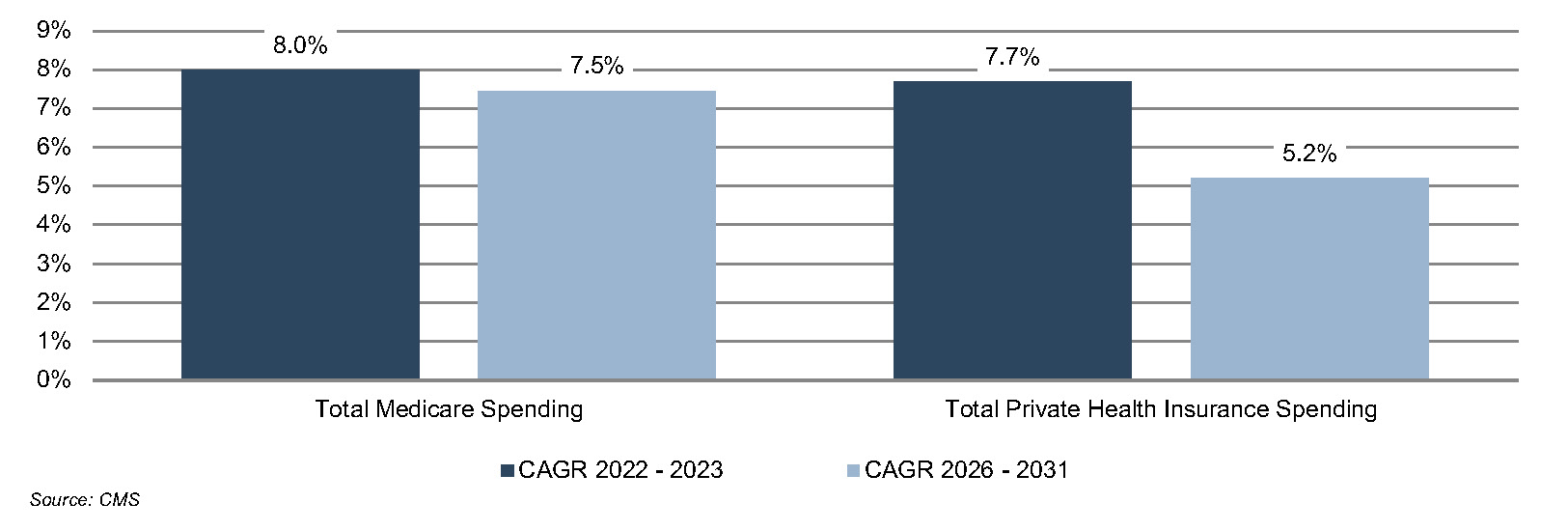

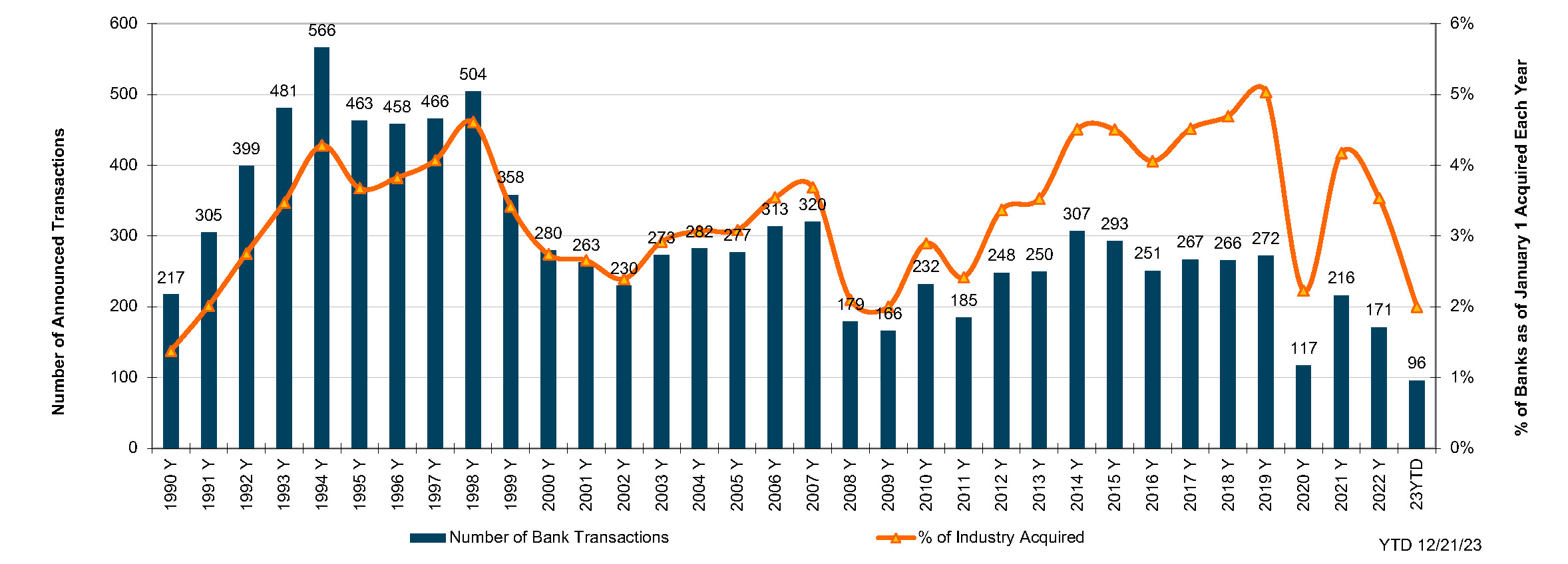

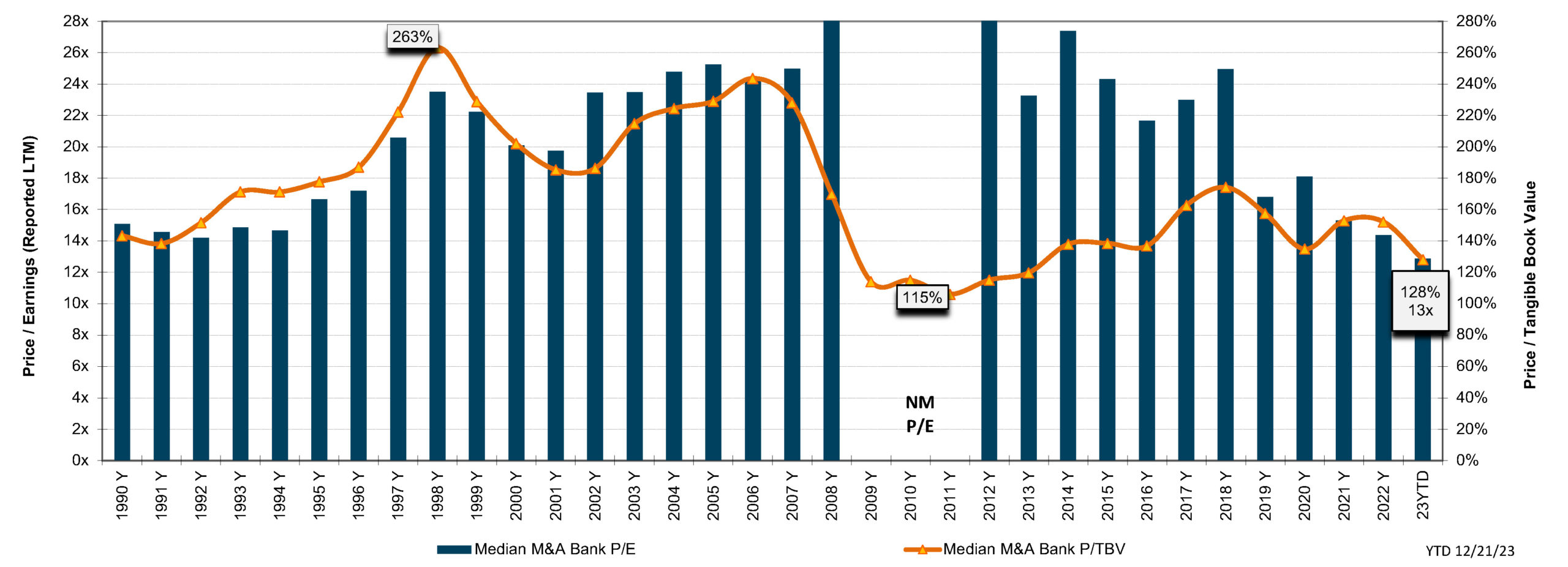

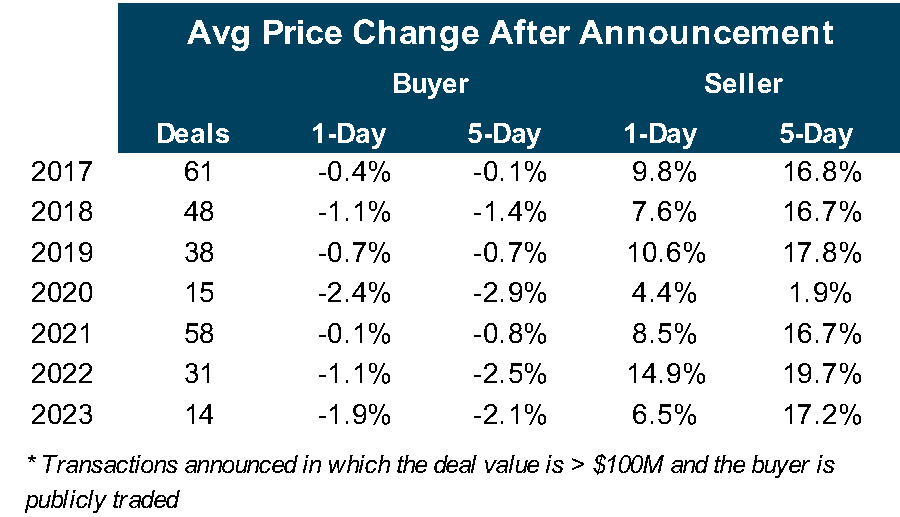

Themes From the 2024 Acquire or Be Acquired Conference

For those who haven’t been to Bank Director’s Acquire or Be Acquired conference (AOBA) before, it is a two-and-a-half-day conference in the desert (Phoenix) that typically includes great weather, golf at the end, and has broadened over the years to focus on a combination of M&A, growth, and FinTech strategies.

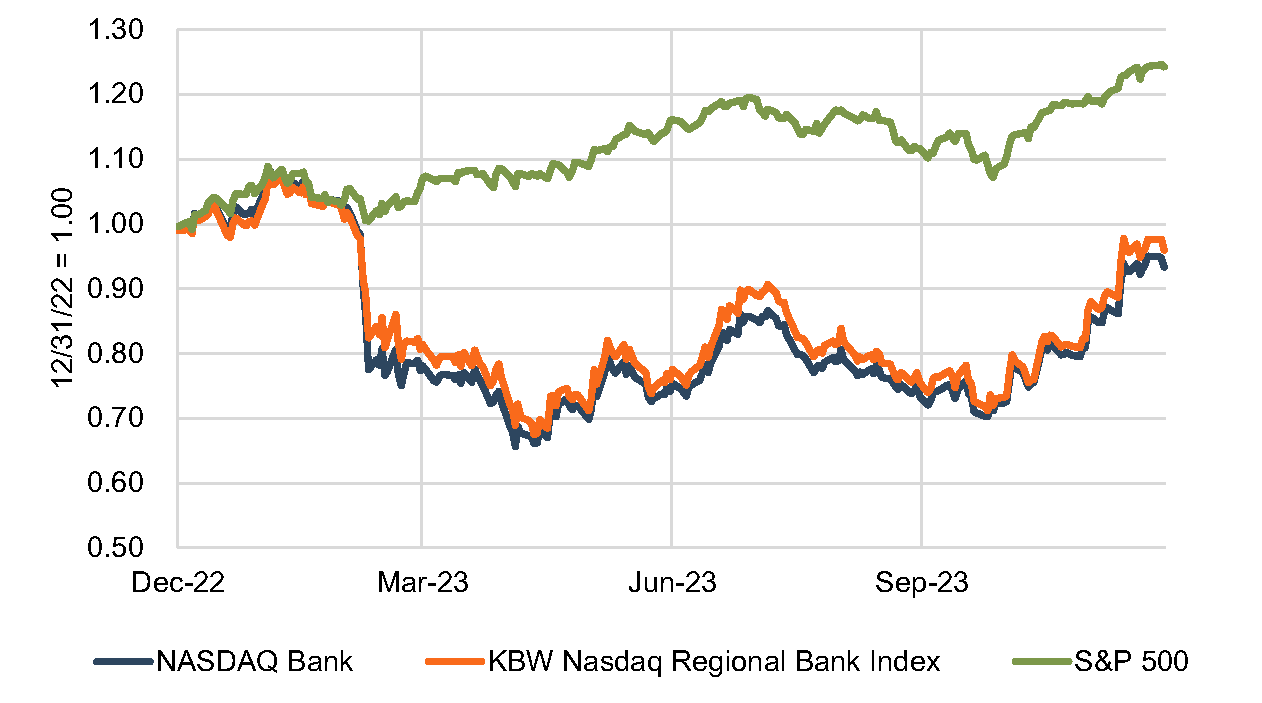

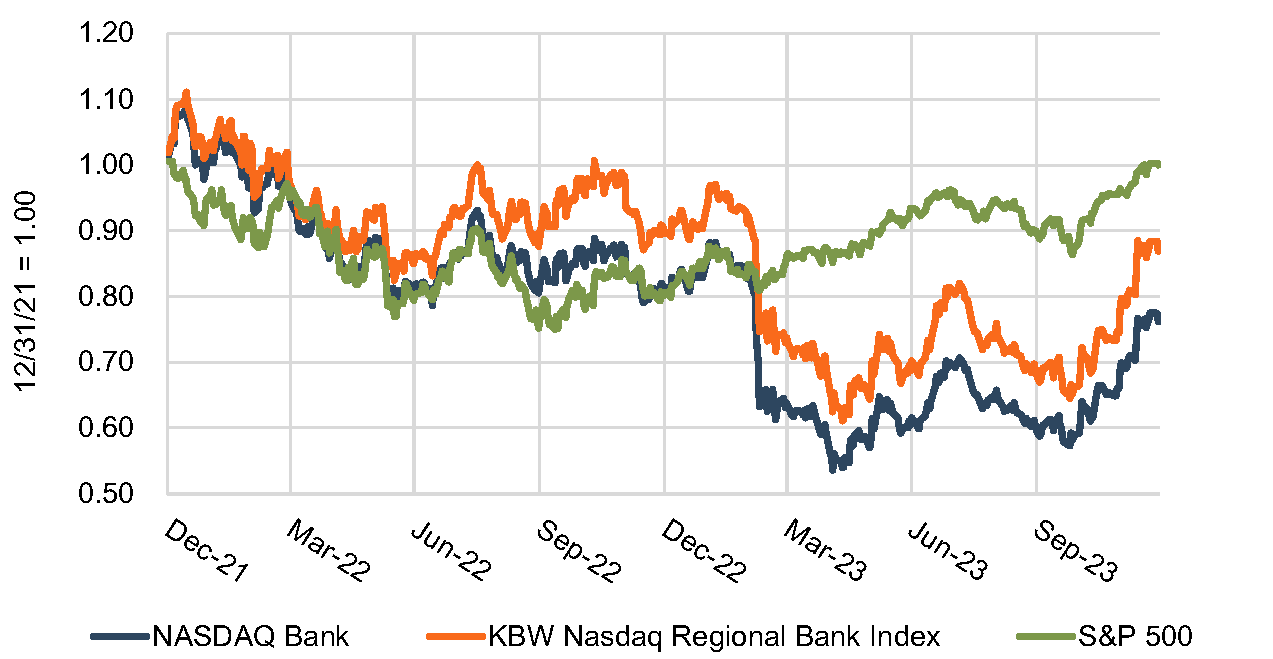

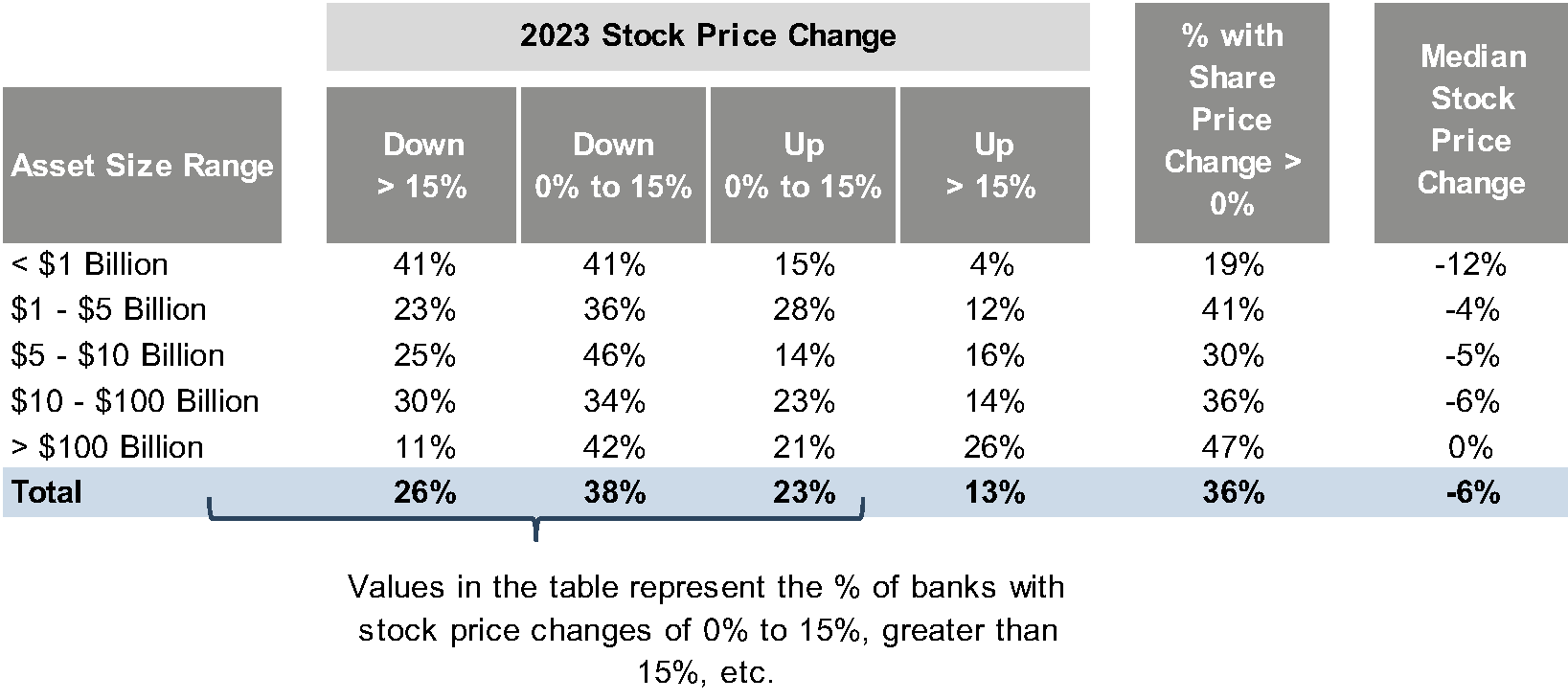

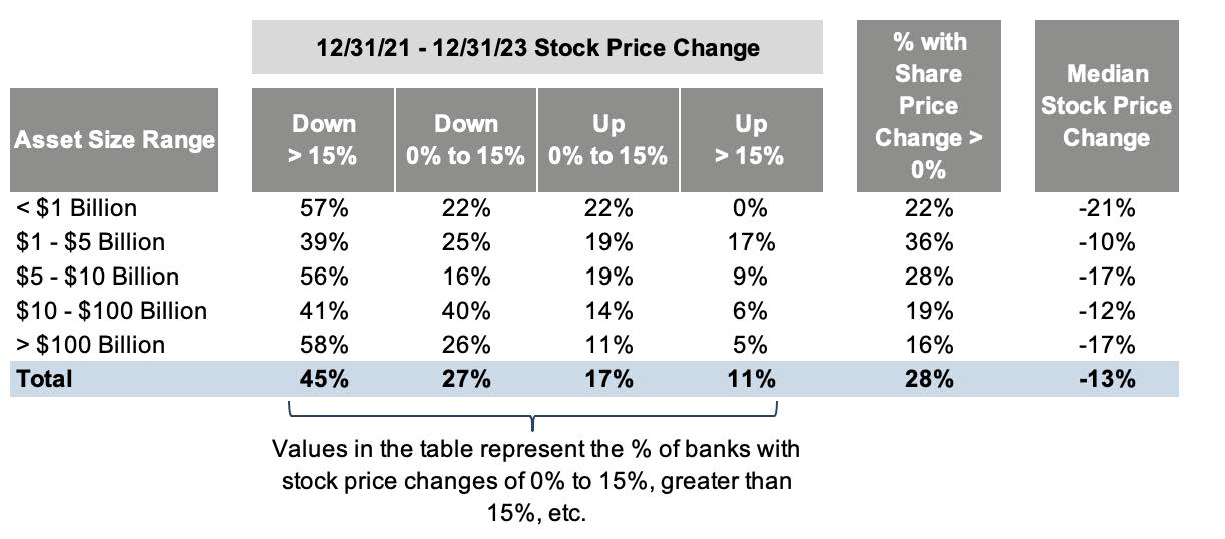

Cautious Optimism

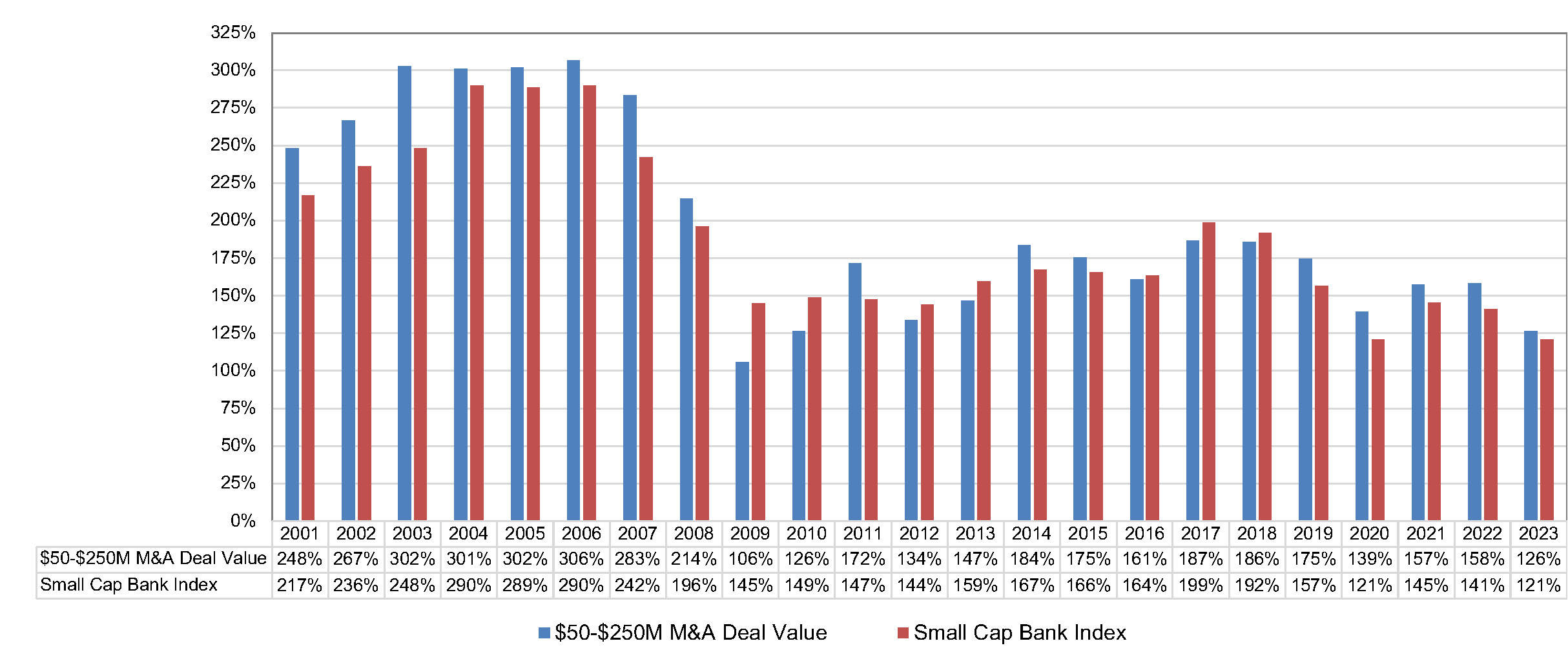

While the 2024 version of AOBA included a number of discussions around headwinds facing the sector, there was optimism for 2024 when compared to 2023. For example, the banking audience was asked during the conference: How do you feel about 2024 compared to your experience in 2023? ~90% responded that they felt more optimistic about 2024 when compared to 2023. Additionally, several sessions noted that optimism exists for an uptick in deal activity in the second half of 2024.

Traditional Bank M&A Tailwinds and Headwinds

While the turbulence and potential headwinds for bank M&A that slowed deal activity in 2023 continue to persist at the outset of 2024, traditional bank M&A remained a much discussed topic at the 2024 AOBA conference. Discussions focused on the nuts and bolts of M&A from valuation to due diligence to structuring and ultimately to integration. While certain themes change and evolve, the strategy to achieve greater scale and growth through M&A and to enhance efficiency and profitability that create value over the long run, persist. The challenging M&A landscape could present an opportunity for acquirers with the balance sheet and capacity to engage in a transaction, and the silver lining for those acquirers may be less competition for sellers as some buyers focus internally during the challenging operating environment.

Balance Sheets in Focus

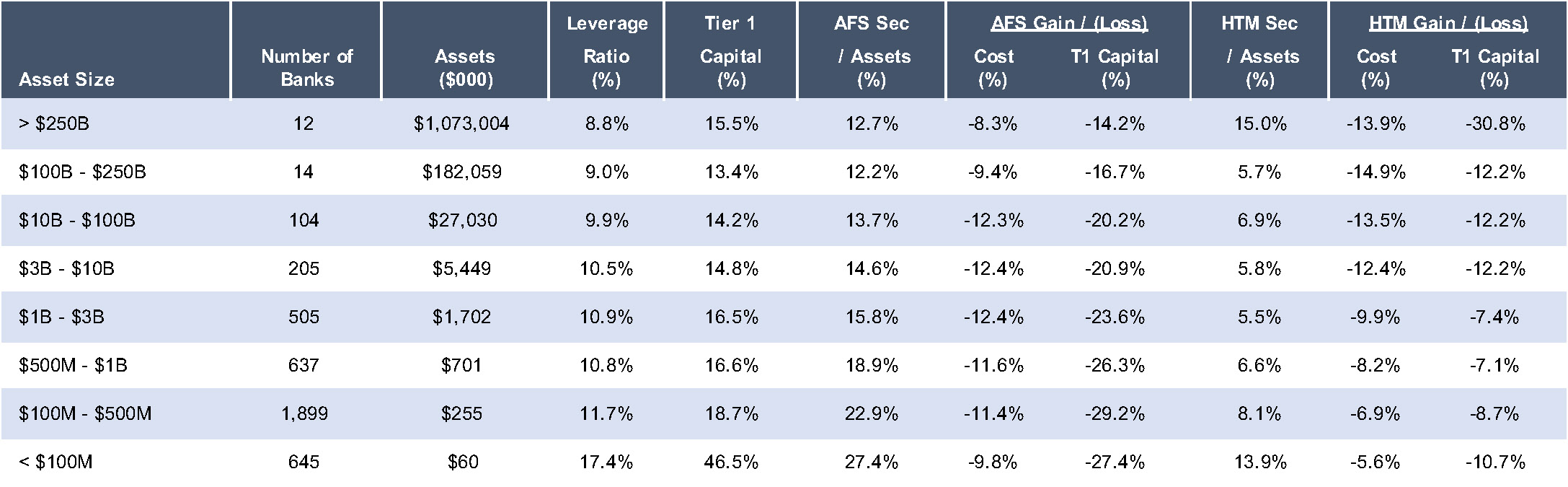

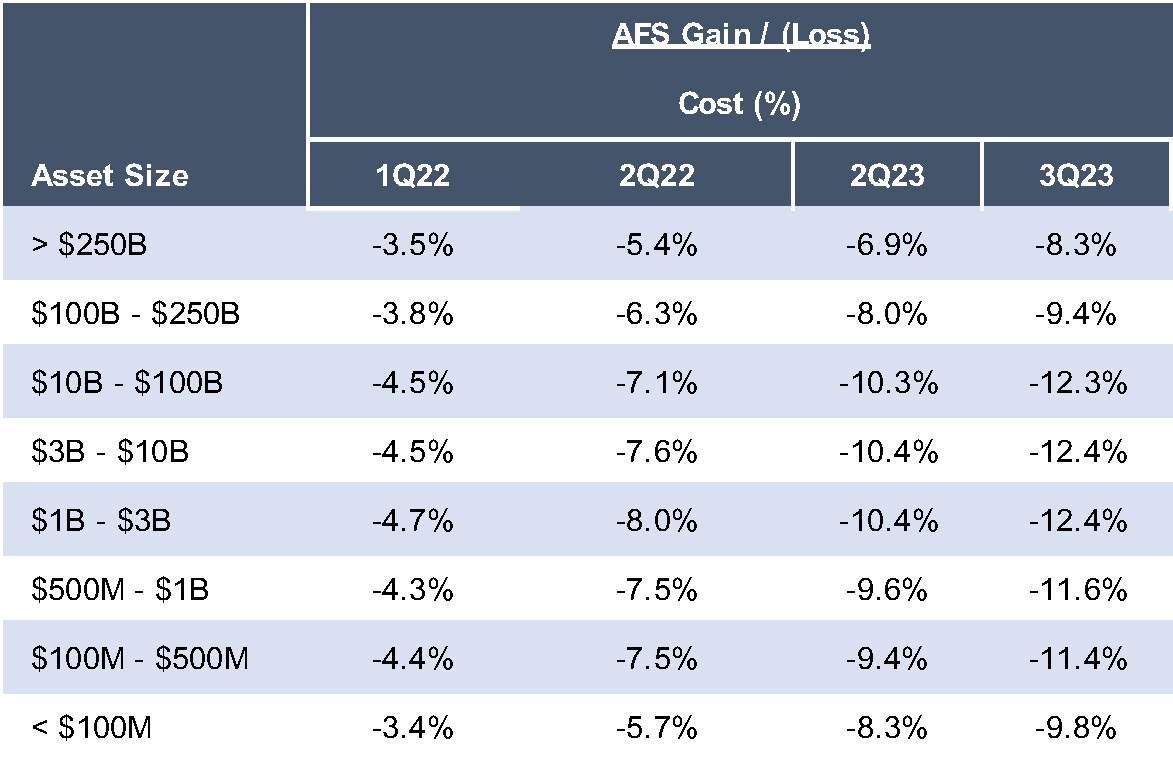

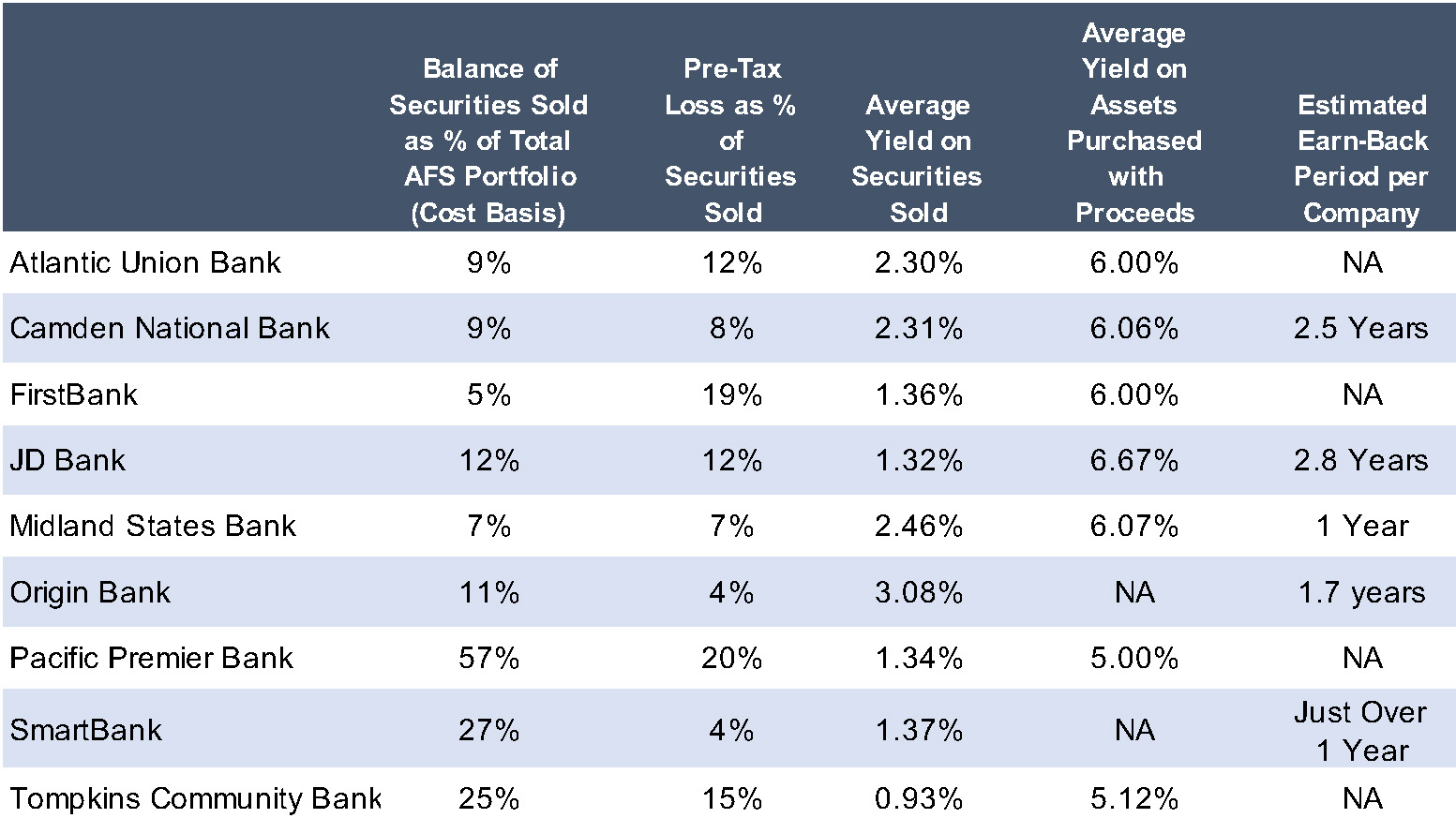

There were definitely more sessions this year discussing balance sheets. A number of sessions noted that one key to dealmaking in the current environment was managing the balance sheet, and several discussed the impact of fair value marks on sellers and pro forma combined balance sheets and the impact on deal activity. For acquirers, a strong balance sheet and capital level can position their institution to be able to take advantage of the current deal environment. For sellers, having a balance sheet that is less impacted from the fair value marks to loans and bonds and with more valuable deposits enhances their attractiveness to potential acquirers. In one session, my colleagues Jeff Davis and Andy Gibbs discussed the impact of taking a loss today on low-coupon bonds that are worth less than the current market price versus holding the bonds to maturity on the value of a bank’s equity. They also reviewed an intermediate strategy referred to as the installment method.

Deposits, Deposits, Deposits

Consistent with discussions around the balance sheet, the interest rate environment, and impact on the banking industry & M&A, discussions about deposits came up often. These discussions covered strategies to retain business or consumer deposits, the attractiveness of core deposits for acquirers in the current environment, how to grow deposits organically (some of the largest banks are even turning back the clock and building branches again), trends in core deposit intangible valuations, and how to provide your customers with the technology and digital banking solutions to onboard and retain deposits more efficiently. One question discussed in several sessions that will be interesting to see the answer to in 2024 was: Has the cost of funds peaked?

Technology Brings Opportunities

Over the last few years, technology has been an increasing topic discussed during sessions of AOBA. Technology topics discussed included leveraging payments to enhance retail and small business banking, using software and/or digital banking to more efficiently make loans and/or open deposit accounts and best practice for developing and managing risk of FinTech partnerships. Even AI, the market’s favorite topic of 2024, was discussed. A consensus on how best to leverage AI in banking has not yet emerged in my view but topics discussed included leveraging AI to enhance loan growth or efficiency of common tasks in the back office. Traditional M&A has historically focused on the potential diversification benefits of combining loan portfolios, deposit portfolios, and geographic footprints but increasingly the tech stacks of buyers and sellers are being compared to see what diversification benefits exist and what the cost may be to combine the tech stack after closing.

Technology Also Brings Potential Risks

One challenging aspect of technology for banks was how best to balance the potential benefits of technology with the risks inherent in them, particularly new technologies and FinTech partnerships. Tech-forward banks and their valuations were also discussed. As we have noted in the past, this tech-forward bank group has seen increased volatility in market performance than their peers as the market digests some of the tech-oriented business models (such as banking-as-a-service) and weighs the potential for higher growth and profitability against the potential risk of these business models and regulatory scrutiny.

Non-Traditional Deals

Similar to traditional bank deals, bank acquisitions in non-traditional areas like specialty finance, insurance, and asset management have been modest and challenging given the difficult operating environment, higher cost of debt, and opportunity cost of excess liquidity. However, there were some discussions around best practices and lessons learned from specialty finance transactions and that additional opportunities may emerge as non-bank lenders also deal with the challenging funding and interest rate environment. Additionally, Truist recently announced the sale of its insurance business to book a gain, focus on core banking, and enhance capital. The announced bank acquisitions by credit unions and private investors also illustrate that non-traditional deals remain a part of a bank’s strategic playbook.

Conclusion

We look forward to discussing these issues with clients in 2024 and monitoring how they evolve within the banking industry over the next year. As always, Mercer Capital is available to discuss these trends as they relate to your financial institution, so feel free to call or email.

Essential Financial Documents to Gather During Divorce – Part 1

Documents Needed to Prepare the Marital Balance Sheet

Prepared by Mercer Capital’s Family Law Services Team

We have written in the past about the benefits of hiring an expert in family law cases, whether it’s expected to settle or go to trial.

In this multi-piece series, we want to provide you with a resource that will assist you and your clients during one of the most difficult times in their lives, both emotionally and financially, and inspired by a recent post we read.

Often, one spouse takes on the primary responsibility of paying bills, filing taxes, and various other management of household finances. During divorce, this can lead the other spouse to feel lost, or at least at a disadvantage.

Mercer Capital has compiled a list of financial documents that are typically needed in the divorce process and decoded common financial terms helpful to attorneys and their clients.

Financial experts can assist in determining the relevant documents based on the facts and circumstances of the case, which can reduce the burden of hunting down extraneous documents. Most financial documents fall into one (or multiple) of the following categories:

- Determining the value of the marital estate (aka marital balance sheet or net worth), and the individual assets and liabilities which comprise such

- Determining income and expenses for spousal and/or child support (akin to an income statement or budget)

- Determining the value of business(es)

- Providing support for forensic services

One of the preliminary financial documents requested, unsurprisingly, is tax returns. We’ve written about this in Mercer Capital’s Navigating Tax Returns: Tips and Key Focus Areas for Family Law Attorneys and Divorcing Individuals/Business Owners, which is a great resource for understanding and reviewing tax returns, particularly for purposes of divorce.

Tax returns report income received from various sources, which is beneficial for various financial analyses, but are also beneficial in constructing the marital balance sheet. Tax returns provide insight into other financial situations such as passive income and even hidden assets.

However, tax returns are dense and may not give as granular of detail as the source documents provided to a CPA who might prepare the returns. For example, the return may not break down W-2 wages by salary/bonus, which is important to making reasonable ongoing compensation determinations. So, while it makes sense that tax returns are a preliminary financial document, they may not be the primary source for information, depending on facts and circumstances.

Another key document to request in the divorce process is a personal financial statement (“PFS”), which is more commonly available to business owners. This is often submitted to a financial institution like a bank when seeking a loan. While usually required for a business loan, it can also be used for a mortgage, and may be required annually by the bank. The PFS provides assets, liabilities and sources of income and assets, which can shortcut the process of “finding” all assets and sources of income for the couple when building the marital balance sheet or determining income for support purposes.

A PFS can also be helpful if a spouse has opined on the value of their business. When applying for a loan, a business owner might be incentivized to view the business through rose-colored glasses. Sometimes, the opposite may be true in divorce, where a divorcing business owner retains the business post-divorce. The term “divorce recession” may come to mind, and the term exists for a reason. As with everything, facts and circumstances matter. The value of a business is not stagnant over time, and the value of a company may look different following a record year as opposed to its worst year. As one of our colleagues likes to say, while the value listed on a PFS is not the data point, it is one of many data points that valuation professionals ought to consider when evaluating a company and preparing for the due diligence interview.

Documents for Marital Balance Sheet (Dividing Up Net Estate)

In most divorce cases, either the expert or attorney will need to prepare a marital balance sheet, or statement of net worth or net estate; this may be referred to differently depending on state and jurisdiction. Divorcing couples may reasonably disagree about the value of the assets and liabilities that they own, and they may further disagree on division of these items. Experts can assist both in developing the list of assets and liabilities and reviewing division scenarios. Our job is easier once we receive documents including statements with contemporaneous balances. This includes:

- Bank statements (checking and savings accounts)

- Any safety deposit box and contents

- Investments/Brokerage accounts statements

- 401k, IRA, and other retirement account statements

- 529 plans (good to be aware of, but commonly not analyzed as these are “separate” assets for the benefit of children)

- List of real estate owned – these may require current appraisals if they were not recently purchased

- List of vehicles, boats, jewelry, etc.

- Airline miles

- List of all business interests

- Investments that have active interest in

- Trusts, wills, etc.

- Mortgage statement

- Credit card statements along with list of credit cards and accounts

- Student Loan statements

- Other debt statements

- Tax refunds/liabilities

- Credit reports

- Insurance (home, life, auto, other assets, etc.)

- Others may be needed depending on circumstances

Conclusion

A financial expert can help in many ways, including focusing the scope of a divorce case, particularly if brought in early to the process with ample time to assist with the various stages of the case. This can reduce duplicative requests and can provide an understanding of why various documents are necessary.

A competent financial expert will be able to define and quantify the financial aspects of a case and effectively communicate the conclusion.

For more information or to discuss your matter with us, please don’t hesitate to contact us.

Essential Financial Documents to Gather During Divorce Series

5 Reasons Buyers Need a Quality of Earnings Report

After sitting on the sidelines for much of 2022 and 2023, the prospect of Fed rate cuts may lure buyers back onto the field in 2024.

And when deal activity heats back up, due diligence will be as critical to buyers as ever. For many buyers, a quality of earnings (“QofE”) report is a cornerstone of their broader diligence efforts.

For businesses, an acquisition that goes sour can negatively affect family wealth for decades to come. Obtaining a thorough QofE report as part of deal diligence can help business directors avoid such a misstep. In this article, we review five reasons business directors need a QofE report before approving an acquisition.

1. Avoid overpaying for earnings that aren’t sustainable.

Audited financial statements provide assurance that the past performance of the target company is faithfully represented. However, successful acquirers are focused on the future, not the past. A thorough QofE report helps buyers extract what truly sustainable performance is from the welter of the target’s historical earnings. Paying for historical earnings that don’t materialize in the future is a recipe for sinking returns on invested capital. QofE reports analyze historical earnings for adjustments that convert historical earnings to the pro forma run rate earnings that make an acquisition worthwhile.

2. Identify opportunities for cost savings in the target’s expense base.

The detailed analysis of cost of sales and operating expenses in a QofE report can uncover opportunities for acquirers to boost margins at the target through cost-saving initiatives. By observing trends in headcount by function, occupancy, and other components of operating expense, buyers can identify redundancies and develop strategies for enhancing post-acquisition cash flow from the target.

3. Find revenue synergies with your existing business.

A thorough QofE report is not just about expenses. Observing revenue trends by product and business segment, coupled with analysis of customer churn data, can help buyers better understand how the target “fits” with the existing business of the buyer, which can open up strategies for fueling revenue growth in excess of what either company could accomplish on a standalone basis. Armed with a better understanding of opportunities for revenue synergies, buyers can move to the closing table more confident of the upside to be unlocked through the transaction.

4. Clarify working capital needs of the target.

Incremental working capital investment is the silent killer of transaction return on investment. A thorough QofE report will move beyond the income statement to evaluate seasonal trends in the core components of net working capital. Doing so helps buyers plan adequately for the ongoing working capital requirements they will need to fund out of post-acquisition earnings. Working capital analysis in the QofE report also helps buyers negotiate appropriate working capital targets in the final purchase agreement.

5. Assess capital expenditure needs at the target.

Not every dollar of EBITDA is equal. EBITDA multiples are a function of risk, growth, and capital intensity. Buyers cannot afford to overlook capital intensity when evaluating targets. A thorough QofE report examines historical trends in capital expenditures and fixed asset turnover to help buyers better discern the prospective capital expenditure needs of the target and how those needs influence the transaction price and prospective returns.

Conclusion

For businesses contemplating an acquisition, the stakes are high. You can’t eliminate risk from an M&A transaction but obtaining a thorough QofE report on the target can help directors avoid mistakes and increase the odds of a successful deal. If you are considering an acquisition, give one of our senior professionals a call to discuss how our QofE team can generate Insights That Matter for your diligence team.

WHITEPAPER

Quality of Earnings Analysis

For buyers and sellers, the stakes in a transaction are high. A QofE report is an essential step in getting the transaction right.

Pay Versus Performance: What’s New in Year 2?

Executive Summary

- The 2024 proxy season marks Year 2 under the SEC’s new Pay Versus Performance disclosure framework for public companies.

- The SEC issued additional guidance over the last year which clarified the requirements and commented upon registrants’ proxy filings from 2023. We discuss several of these items pertaining to valuation and equity-based compensation in this article.

- Newly public companies and those private companies aspiring to list in the future should be aware of the disclosure and valuation requirements related to Compensation Actually Paid for senior executives.

- With respect to equity-based awards such as stock options and performance shares with market conditions, the rules continue to point to alignment with ASC 718 and require the disclosure of any significant change in valuation techniques and assumptions.

- Registrants and their advisors should pay particular attention to the impact of changes in key assumptions on the fair value of equity awards, including volatility, realized performance, and changes in the composition of total shareholder return (TSR) peer groups.

Introduction

The SEC’s Pay Versus Performance disclosure rules introduced significant new valuation requirements related to equity-based compensation paid to company executives. As the 2024 proxy season gets underway, what lessons have been learned and what guidance has the SEC provided to registrants? We discuss some of the SEC’s recent Compliance & Disclosure Interpretations and share some best practices as companies gear up for Year 2 of the new Pay Versus Performance framework.

To recap how we got to this point, the new disclosures were mandated by the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act and were originally proposed by the SEC in 2015. These rules added a new item 402(v) to Regulation S-K and are intended to provide investors with more transparent, readily comparable, and understandable disclosure of a registrant’s executive compensation. The new provisions apply to all reporting companies other than (i) foreign private issuers, (ii) registered investment companies, and (iii) emerging growth companies.

The rules apply to any proxy and information statement where shareholders are voting on directors or executive compensation that is filed in respect of a fiscal year ending on or after December 16, 2022. As such, the vast majority of registrants were required to include these disclosures in their 2023 proxy statements, with scaled-down disclosures for smaller reporting companies.

For a more technical discussion of the rules, see our earlier article 5 Things to Know About the SEC’s New Pay Versus Performance Rules.

Valuation-Related Takeaways from the SEC Guidance

The Pay Versus Performance rules require registrants to disclose the fair value of equity awards to certain senior executives in the year granted and to report changes in the fair value of the awards until they vest. Practically speaking, this means that it is necessary to measure the year-end fair value of all outstanding and unvested equity awards under a methodology consistent with what the registrant uses in its financial statements (e.g., ASC 718, Compensation – Stock Compensation).

In 2023, the SEC issued a series of Compliance & Disclosure Interpretations (C&DIs) relating to the Pay Versus Performance disclosure requirements. The roughly 30 C&DIs issued in 2023 are structured in a question-and-answer format. While the questions address many different aspects of the requirements, we focus our summary on those that pertain to valuation-related issues. In the sections that follow, we summarize each question and answer for clarity.

Question 128D.14 (Treatment of Awards Granted Prior to a Restructuring or Spin-Off)

Should awards granted in fiscal years prior to an equity restructuring, such as a spin-off, that are retained by the holder be included in the calculation of executive compensation actually paid?

Answer: Yes. All stock awards and option awards that are outstanding and unvested at the beginning of the covered fiscal year or are granted to the principal executive officer and the remaining named executive officers during the covered fiscal year should be included in the CAP table.

Question 128D.15 (Using Private Company Prices for Newly Public Companies)

For a newly public company (e.g., IPO or SPAC) complying with the proxy statement rules for the first time, should the change in fair value of awards granted prior to IPO be based on the fair value of those awards as of the end of the prior fiscal year for purposes of determining executive compensation actually paid?

Answer: Yes. For outstanding stock awards and option awards, the calculations required by Regulation S-K should be determined based on the change in fair value from the end of the prior fiscal year. The fair value of these awards should not be determined based on other dates, such as the date of the registrant’s IPO. This means that prior private company valuations (such as for 409A or ASC 718) could come into play when preparing future Pay Versus Performance disclosures.

Questions 128D.16-17 (Inclusion of Market Conditions in Fair Value)

How should awards with a market condition consider that condition in determining whether the applicable vesting conditions have been met in performing the CAP calculations?

Answer: The effect of a market condition should be reflected in the fair value of share-based awards with such a condition. Until the market condition is satisfied, registrants must include in executive compensation actually paid any change in fair value of any awards subject to market conditions. Similarly, registrants must deduct the amount of the fair value at the end of the prior fiscal year for awards that fail to meet the market condition during the covered fiscal year if it results in forfeiture of the award. However, awards that remain outstanding and have not yet vested should not be considered forfeited.

Question 128D.20 (Use of a Different Valuation Technique)

Can a registrant use a different valuation technique for Pay Versus Performance calculations than what was used for grant date fair value?

Answer: Yes, as long as the valuation technique would be permitted under ASC 718, including that it meets the criteria for a valuation technique and the fair value measurement objective. For example, another valuation technique might provide a better estimate of fair value subsequent to the grant date. The rules require disclosure about the assumptions made in the valuation that differ materially from those disclosed as of the grant date. A change in valuation technique from the technique used at the grant date would require disclosure of the change and the reason for the change if such technique differs materially.

Question 128D.21 (Use of Non-GAAP Methods or Shortcuts)

Is it ever acceptable to value stock and/or option awards as of the end of a covered fiscal year based on methods not prescribed by GAAP?

Answer: No. The fair value of equity awards must be computed using methodology and assumptions consistent with ASC 718. For example, the expected term assumption to value options should not be determined using a “shortcut approach” that simply subtracts the elapsed actual life from the expected term assumption at the grant date. Similarly, the expected term for options referred to as “plain vanilla” should not be determined using the “simplified” method if those options do not meet the “plain vanilla” criteria at the re-measurement date, such as when the option is now out-of-the-money.

Assumptions to Watch in Year 2 Fair Value Disclosures

The procedures used to calculate fair value vary depending on the type of equity award. For stock options and stock appreciation rights (SARs), fair value is often calculated using a Black-Scholes or lattice model. When rolling prior grant valuations forward, care should be taken to ensure that the expected term appropriately considers moneyness of the options at the new date.

Performance shares and performance share units often include a performance condition (e.g., the award vests if revenues increase by 10%) or a market condition (e.g., the award vests if the registrant’s total shareholder return over a three-year period exceeds its peer group by at least 5%). The performance condition will require updated probability estimates at year-end and at the vesting date. Awards with market conditions are typically valued using Monte Carlo simulation and so a reassessment at subsequent dates using a consistent simulation model with updated assumptions will be necessary. For awards with market conditions, key assumptions to watch in Year 2 updates include:

Volatility – The volatility input should be updated to match the remaining term of the award. If the award is benchmarked to an index or group of peer companies, then the volatility (and correlation factor) for the benchmark should also be reevaluated. Shorter terms might also mean that forward-looking option-implied volatility could be more appropriate than historical approaches.

Realized Performance – When updating the fair value of a three-year award after one year of performance, one-third of the ultimate return (and potential payoff) is already locked in. For companies whose stocks have performed well (either individually or against their peer group), this could lead to a substantial increase in the fair value of the award. On the other hand, a company whose stock price has lagged its peer group could see the value of the award decline drastically, with little likelihood of favorable outcomes possible in the simulation model.

Relative TSR Peer Group Changes – For awards that link payouts to the performance of a group of peer companies or an index, some of the peers may have been acquired or merged since the grant date. The plan documentation will often describe the steps to be taken when the composition of the peer group changes or there is a change in the benchmark index. A different group (or number) of companies will affect the correlation assumption as well as the percentile calculations in a ranked plan.

These are just a few of the assumptions used in the valuation of equity awards. Ultimately, the valuation professional should assess the concluded values for reasonableness and be able to explain why the fair value moved as it did. This understanding provides the link to the calculation of Compensation Actually Paid (and the company’s explanation for it) in the Pay Versus Performance disclosures.

Summary and Next Steps

With Year 2 of the Pay Versus Performance framework underway, registrants and their advisors now have an understanding of what is expected. Further, the SEC’s additional guidance clarified several areas of potential confusion around the valuation of equity awards with market conditions and situations faced by newly public companies. Companies should pay particular attention to the impact of changes in key assumptions on the fair value of equity awards, including volatility, realized performance, and changes in the composition of total shareholder return (TSR) peer groups.

The complexity of implementing the Pay Versus Performance rules in Year 2 will vary by firm. We have already assisted clients with the transition from the initial Year 1 implementation to a roll-forward of previously-valued equity awards. And we certainly understand how the disclosure rules can seem daunting for those new firms who will be complying with the rules for the first time. Ultimately, the individual equity award characteristics will determine the complexity of the valuation process and the number of valuations that need to be performed.

If you have questions about the valuation of equity awards and how they are incorporated into the Pay Versus Performance disclosure framework, please contact a Mercer Capital professional.

Stock-Based Compensation in Volatile Markets

Employee, Management, and Investor Perspectives

Executive Summary

- Over the past decade stock-based compensation (SBC) gained widespread popularity as a way to reward employees while conserving cash.

- Turmoil in the stock market during 2022 resulted in employees seeing diminishing value in SBC and investors questioning its aggressive use.

- In this article, we discuss how market volatility can affect employee, management, and investor perspectives on SBC.

For the most part, we are all familiar with the pitch for stock-based compensation (SBC). For employees, SBC supplements cash compensation with equity ownership in the employer company. Employees get to share in the upside of the company’s growth and success, aligning their interests with that of the company and other shareholders. For employers, SBC is a cash-efficient way to finance operating expenses. SBC can be particularly beneficial for startups or development-stage companies looking to compete for top talent by trading future growth prospects for current cash outlay. Further, SBC can assist with employee retention, as the shares or options granted through SBC arrangements vest over a number of years.

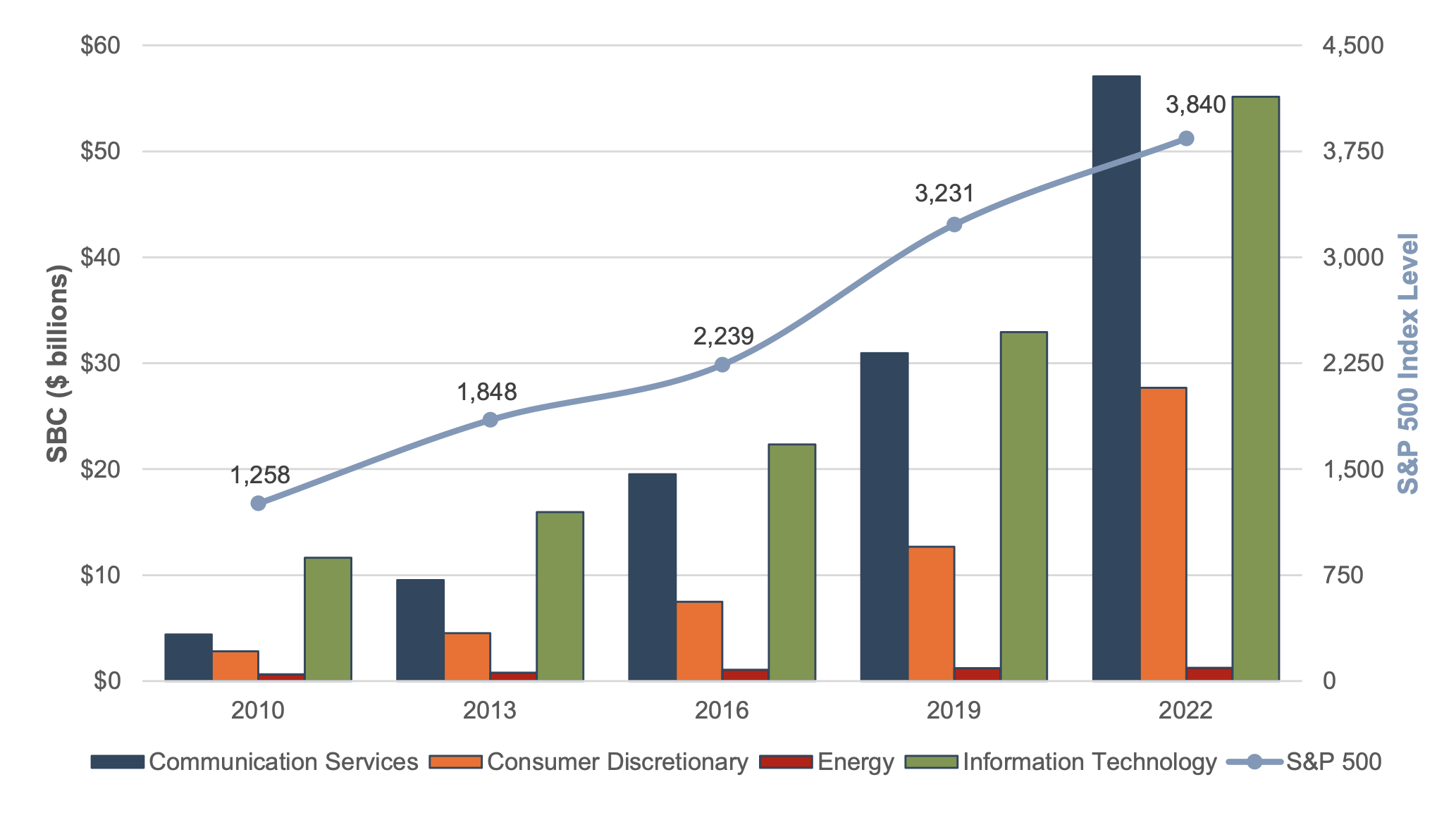

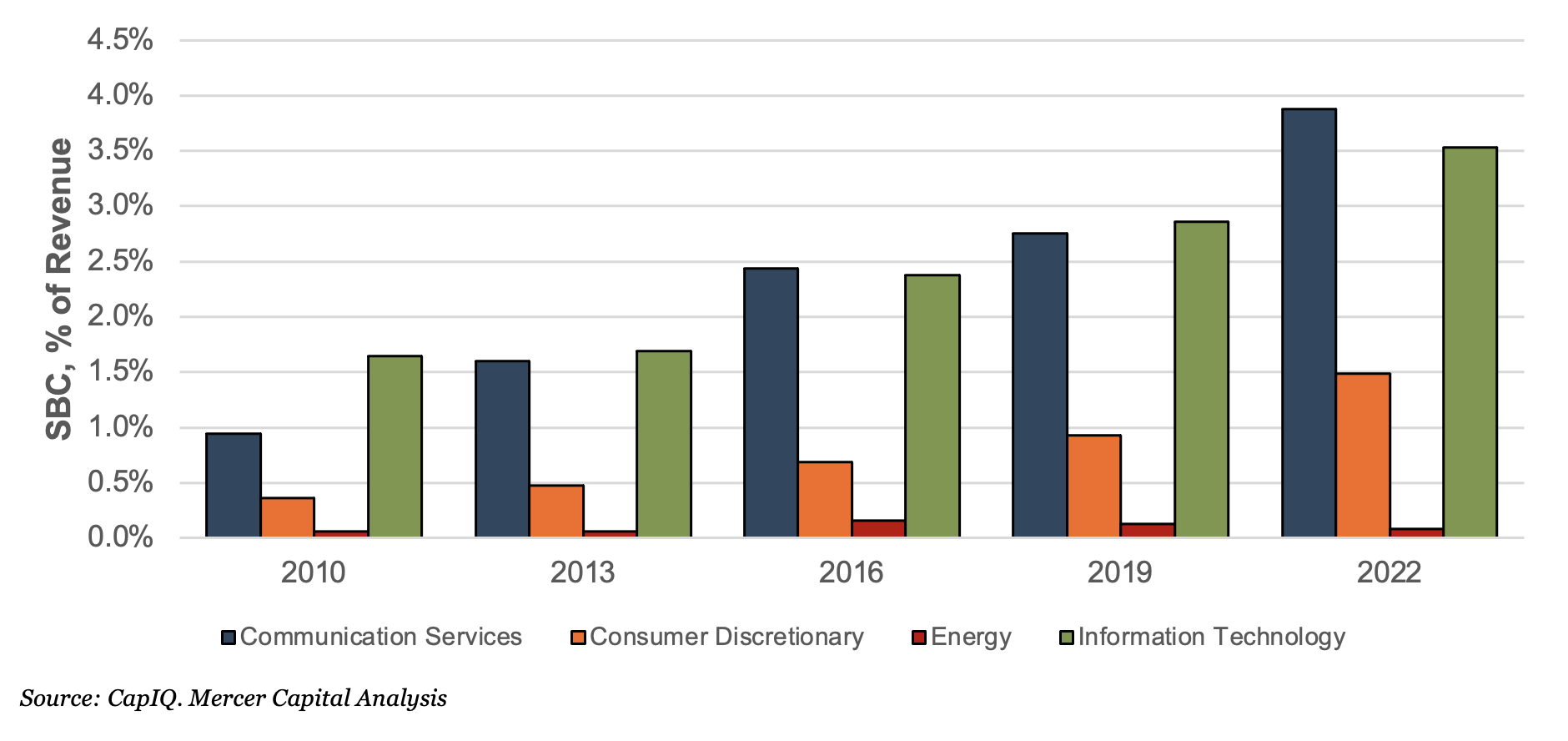

Everyone Seems to Agree SBC Is Good

Indeed, companies across many sectors appear to have been increasingly convinced of the benefits of SBC in the period following the financial crisis. The following charts illustrate SBC expense trends among S&P 500 companies in certain sectors between 2010 and 2022.

Overall, reported SBC for companies in the S&P 500 grew more than 10% annually between 2010 and 2022, reaching a total of $192 billion in 2022 (approximately 1.2% of revenue). Technology-focused companies, many of whom graduated from the startup stage, are among the most prolific users of SBC. The communication services sector reported $57 billion in SBC expenses in 2022, an almost 13-fold increase since 2010. The information technology sector reported the largest SBC expenses in 2010 and remained among its more prominent users in 2022. But the use of SBC has proliferated beyond the technology-focused companies, as well. For example, reported SBC as a proportion of revenue increased more than four times between 2010 and 2022 for the consumer discretionary sector.

Some sectors were holdouts, however. Reported SBC expenses by companies in the energy sector grew at a relatively paltry 3.8% annually between 2010 and 2022.

SBC Expense Trends Among S&P 500 Companies

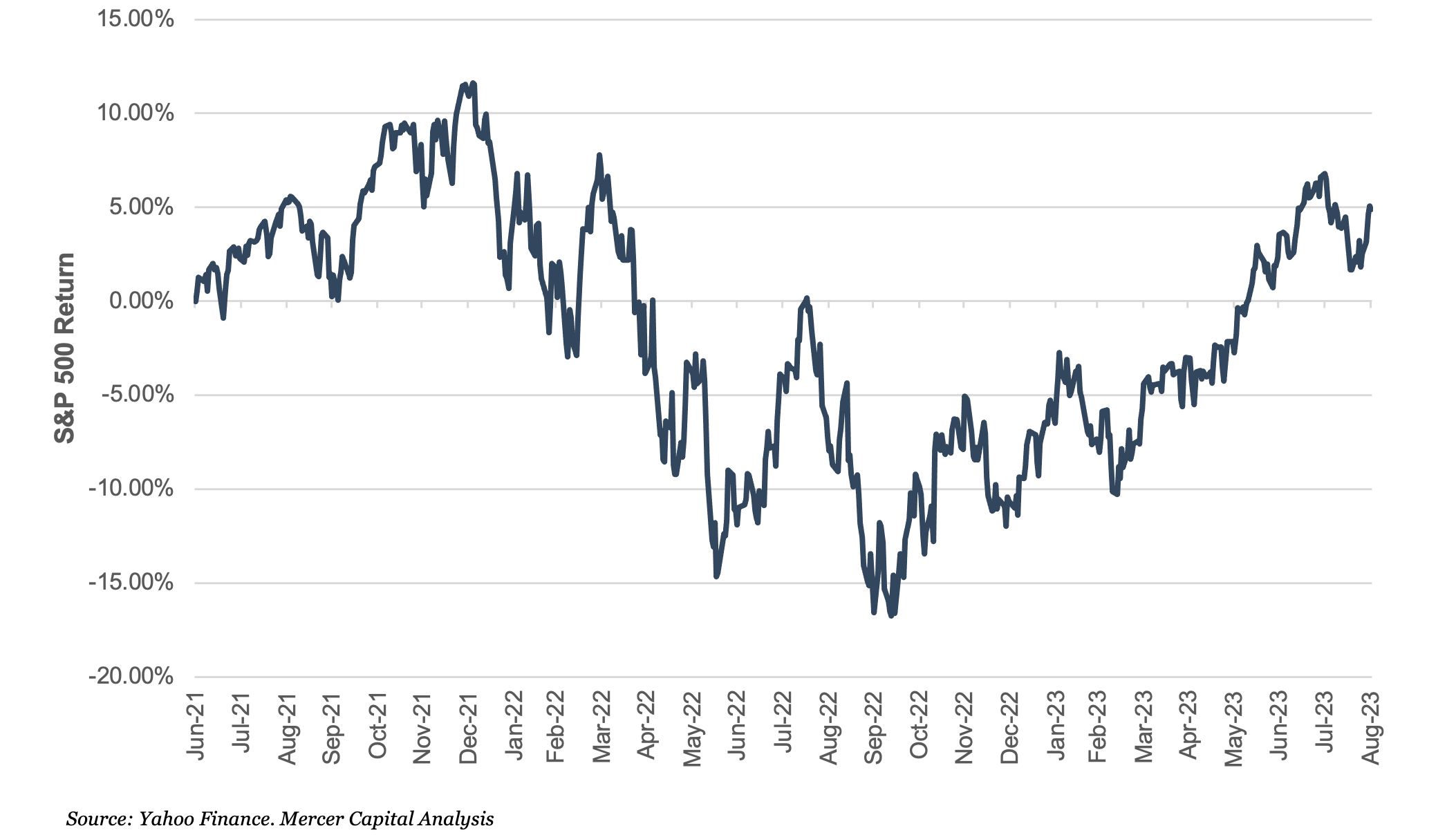

Stocks Go Up, Stocks Go Down

So, has a consensus been reached regarding the benefits of SBC? Not quite. Until 2022, the period after the financial crisis had been marked by sustained gains in the equity markets. The S&P 500 took a tumble during 2022 (falling approximately 20% during the year) before recovering some in 2023. As it relates to SBC, it would appear that when stock prices go up, all stakeholders are similarly happy. When stock prices fall, different stakeholders are unhappy in their own ways.

S&P 500 Relative Performance (June 30, 2021 = 1)

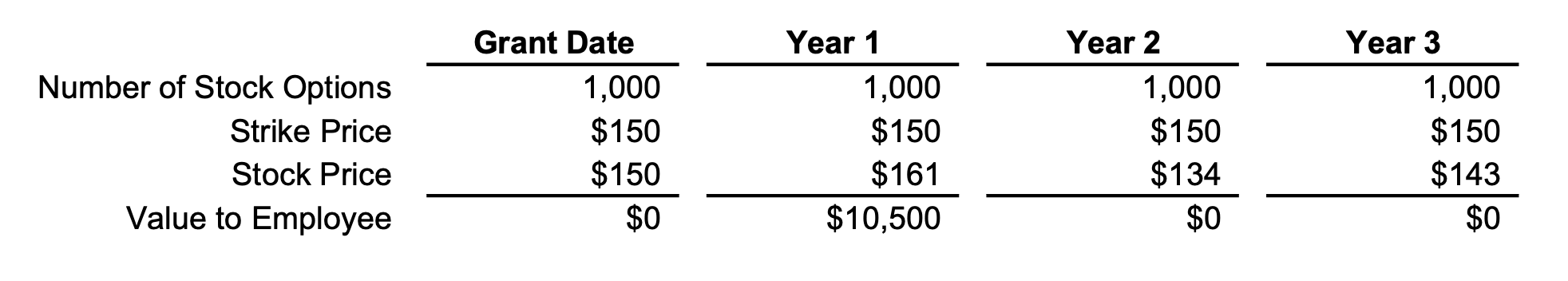

Employee Perspective: Underwater SBC

During 2022, employees were vocal about the diminishing values of the SBC they had received in the past.

Unlike cash compensation, the value of SBC can go up or down over the holding period. For example, say an employee was granted 1,000 restricted stock units (RSUs) in Company X that vest over a 4-year period, when the stock price was $225 per share. At grant, the employee would likely believe she had received $225,000 in compensation, save for a potential haircut to reflect the likelihood of vesting. If one year after grant, Company X’s stock drops 16.7% (similar to the draw down in the S&P 500 between July 2021 and mid-October 2022) to $187 per share, the employee could feel shortchanged by about $37,575.