Navigating Tax Returns: Tips and Key Focus Areas for Family Law Attorneys and Divorcing Individuals/Business Owners – Part II

Part II of III- Schedule A (Form 1040) Itemized Deductions

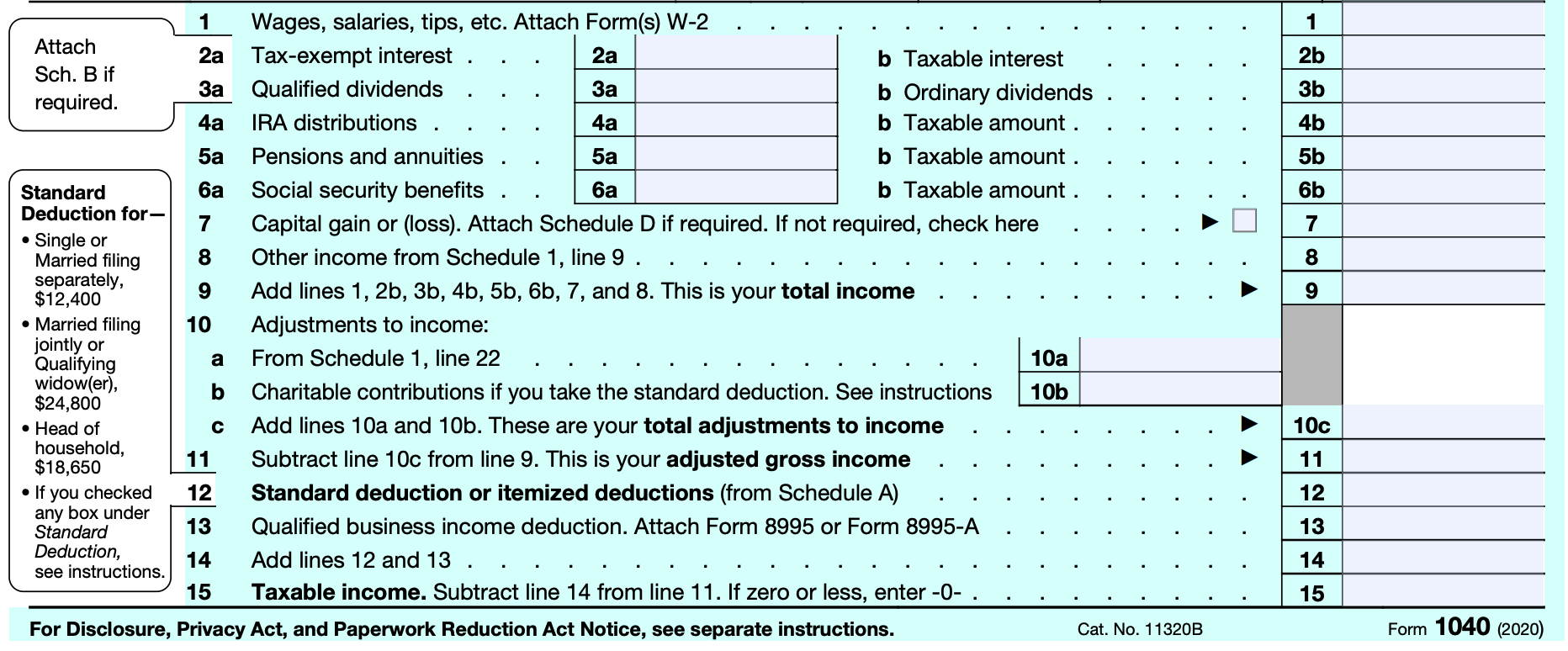

This is the second of the three-part series where we focus on the key areas of tax returns to assist family lawyers and divorcing parties. Part II concentrates on Schedule A (Form 1040) Itemized Deductions. Part I discussed Form 1040 and can be found here.

Schedule A (Form 1040) Itemized Deductions is an attachment to Form 1040 for taxpayers who choose to itemize their tax-deductible expenses rather than take the standard deduction.

Why Would Schedule A (Form 1040) Itemized Deductions Be Important In Divorce Proceedings?

Schedule A provides information regarding marital property – assets and debts – and may reveal information about the taxpayer’s lifestyle and financial position. Reviewing the detailed information can potentially lead to further investigation such as uncovering dissipation of assets, discovering hidden assets, or providing an overview of true historical spending.

Taxpayers have the option on Line 12 of Form 1040 to elect the standard deduction or the itemized deductions from Schedule A. At the time of publication of this article, the standard deduction ranges from $12,400-$24,800 depending on the selected filing status of the taxpayer(s). Both deductions reduce the amount of Taxable Income on Line 15 on Form 1040. If the taxpayer’s qualified itemized deductions are greater than their standard deduction, the taxpayer typically forgoes the standard deduction and files Schedule A with Form 1040. For divorce purposes, reviewing the taxpayer’s elections over a historical period may also provide further insight into the financial snapshot of the estate over time.

Key Areas of Focus for Family Law Attorneys and Divorcing Parties

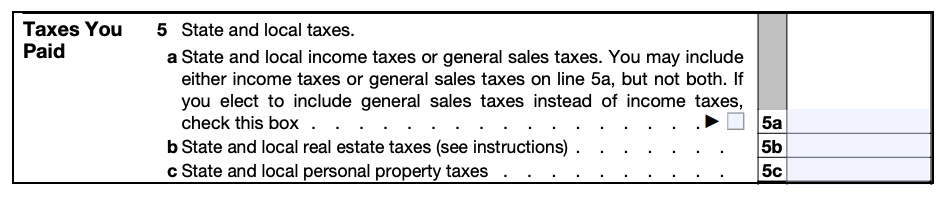

Lines 5b and 5c: State & Local Real Estate Taxes, State & Local Property Taxes – Entries on Lines 5b and/or 5c show taxes paid on property. Line 5b focuses on state and local taxes paid on real estate owned by the taxpayer(s) that were not used for business, while Line 5c concentrates on state and local personal property taxes paid on a yearly basis based on the value of the asset alone.

If these lines are filled, it should lead to further questioning about what these properties are and if they are marital property. The amount of tax paid could also give insight into the taxpayer’s assets. Greater state and local real estate taxes entered on Line 5b usually indicate more expensive real estate. Similarly, a larger entry in Line 5c representing taxes on personal property indicate high-priced assets, such as an expensive car.

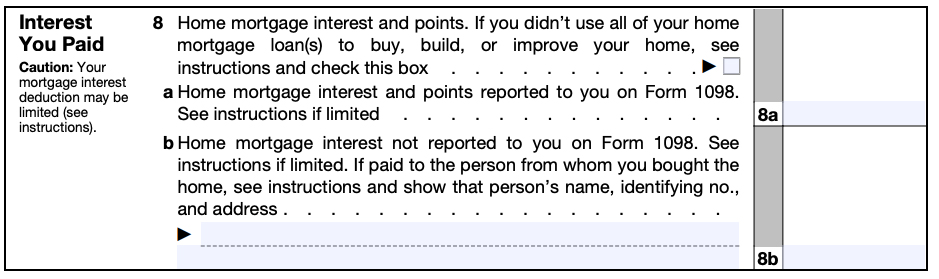

Line 8: Home Mortgage Interest – A home mortgage represents any loan that is secured by the taxpayer’s main home or second home. A “home” can be a house, condominium, mobile home, boat, or similar property as long as it provides the basic living accommodations. The rules for deducting interest vary, depending on whether the loan proceeds are used for business, personal, or investment activities. The deduction for home mortgage interest depends on factors such as the date of the mortgage, the amount of the mortgage, and how the mortgage proceeds are used.

An entry in Lines 8a-e indicates the taxpayer(s) has a home mortgage loan and documentation of the loan should be requested. This line is an indication of property ownership, and therefore, a potential marital asset (or separate asset if that scenario is applicable). Form 1098, the Mortgage Interest Statement, will provide more detailed information.

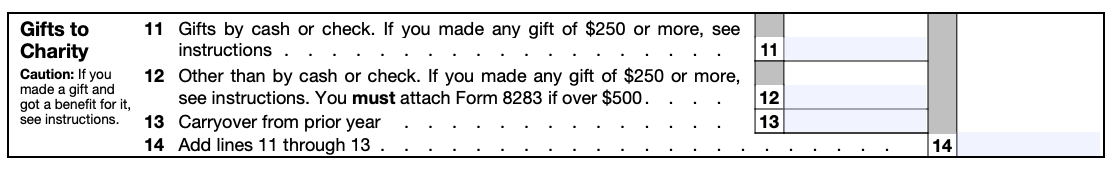

Line 14: Gifts to Charity – A charitable contribution is a donation or gift made voluntarily to, or for the use of, a qualified organization without expecting to receive anything of equal value. Qualified organizations include but are not limited to nonprofit groups that are religious, charitable, or educational.

Sometimes we see charitable giving allocated as a line item in a divorcing individual’s future budget. While this may not necessarily be an expense necessary for traditional living expenses, if, historically, the parties donated significant monies, this can be captured on historical charitable donation deductions and ought to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. As a tip, sometimes these gifts may be captured elsewhere than a personal tax return, such as a trust’s estate tax return.

Line 16: Other Itemized Deductions – Only certain expenses qualify to be deducted as other itemized deductions including gambling losses, casualty and theft losses, among others. If there is an entry in Line 16, more detailed information on these deductions may be necessary.

A common “other itemized deduction” is for gambling losses, which may lead to further questioning and could potentially be dissipation of marital assets. Another example is the federal estate tax on income in respect of a decedent. Income in respect of a decedent (IRD) is income that was owed to a decedent at the time he or she died. Examples of IRD include retirement plan assets, IRA distributions, unpaid interest, dividends, and salary, to name only a few.

Along with other estate assets, IRD is eventually distributed to the beneficiaries. While most assets of the estate are transferred free of income tax, IRD assets are generally taxed at the beneficiaries’ ordinary income tax rates. However, if a decedent’s estate has paid federal estate taxes on the IRD assets, the beneficiary may be eligible for an IRD tax deduction based on the amount of estate tax paid. This is an example of a potential separate asset, however, the IRD could also be a marital asset depending on the beneficiary designation and/or potential commingling of assets.

Items included within other itemized deductions should typically be reviewed and potentially further investigated as they may represent assets, liabilities, and/or sources of income, whether marital or separate.

Conclusion

Understanding how to navigate key areas of Schedule A (Form 1040) can be very helpful in divorce proceedings. Information within Schedule A can provide support for marital assets and liabilities, sources of income and potential further analyses. Reviewing multiple years of tax returns and accompanying supplemental schedules may provide helpful information on trends and/or changes and could indicate the need for potential forensic investigations.

Mercer Capital is a national business valuation and financial advisory firm. While we do not provide tax advice, we have expertise in the areas of financial, valuation, and forensic services.

Value Drivers in Flux

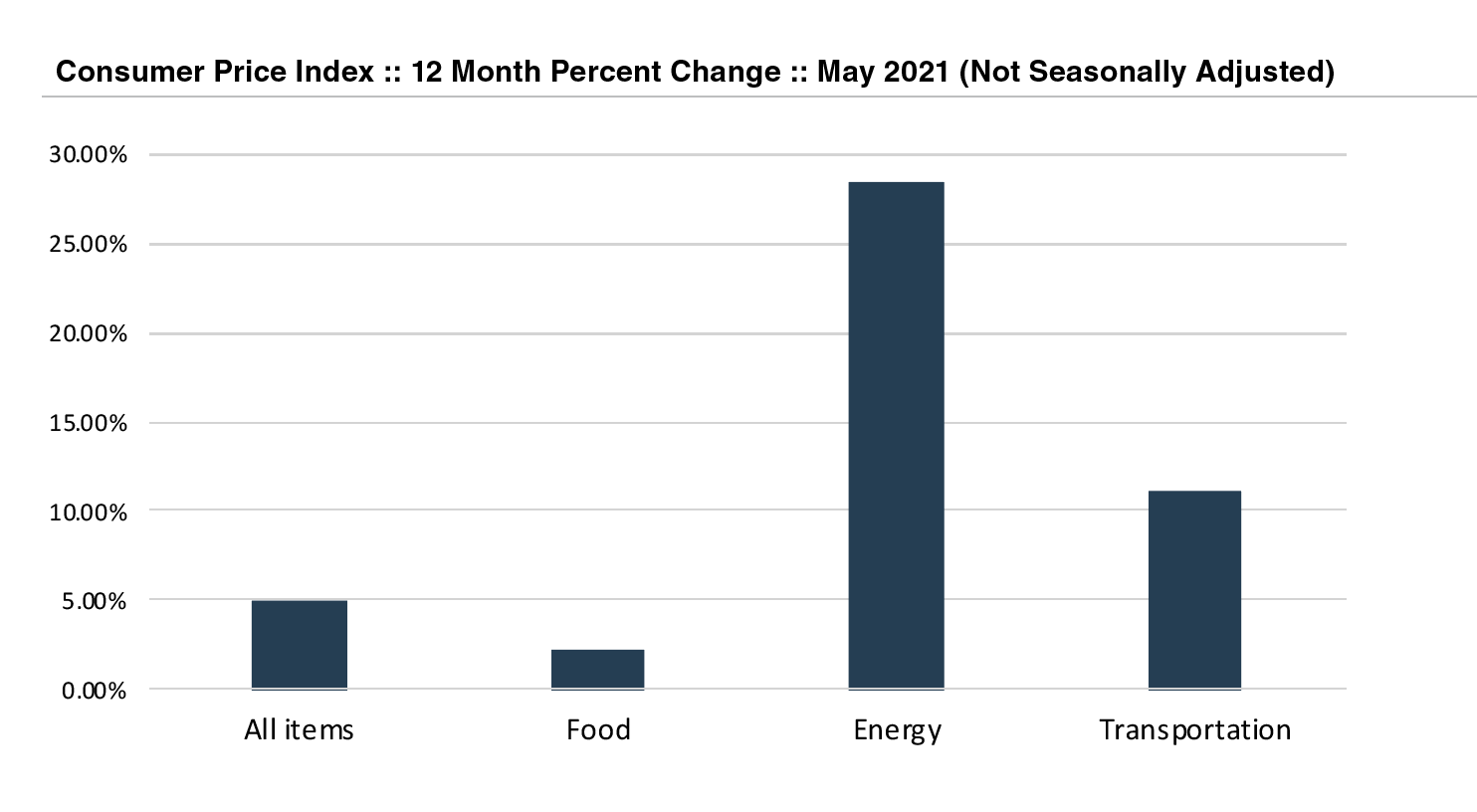

Last July I gave a presentation to the third-year students attending the Consumer Bankers Association’s Executive Banking School. The presentation, which can be found here, touched on three big valuation themes for bank investors: estimate revisions, earning power and long-term growth.

Although Wall Street is overly focused on the quarterly earnings process, investors care because of what quarterly results imply about earnings (or cash flow) estimates for the next year and more generally about a company’s earning power. Earning beats that are based upon fundamentals of faster revenue growth and/or positive operating leverage usually will result in rising estimates and an increase in the share price. The opposite is true, too.

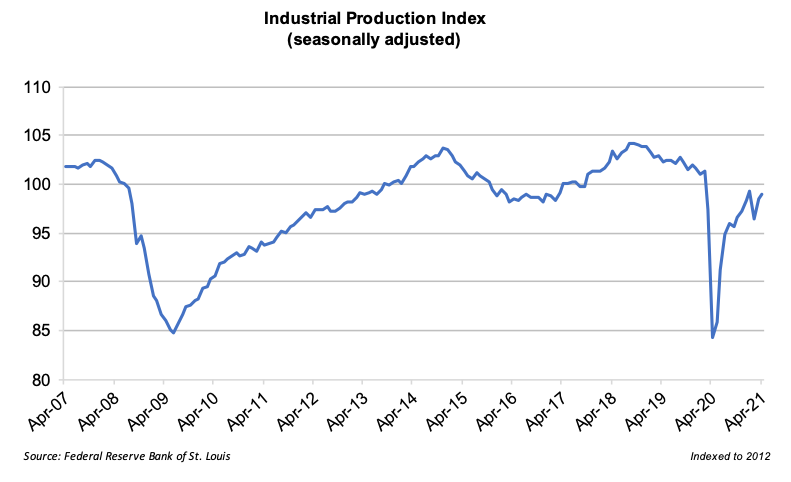

For U.S. banks that have largely finished reporting third quarter results, questions about all three—especially earning power—are in flux more than usual. Industry profitability has always been cyclical, but what is normal depends. Since the early 1980s, there have been fewer recessions that have resulted in long periods of low credit costs. Monetary policy has been radical since 2008. What’s normal was also distorted in 2020 and 2021 by PPP income that padded earnings but will evaporate in 2023.

Most banks beat consensus EPS estimates, largely due to negligible credit costs if not negative loan loss provisions as COVID-19 related reserve builds that occurred in 2020 proved to be too much; however, there was no new news with the earnings release as it relates to credit.

Investors concluded with the release of third and fourth quarter 2020 results that credit losses would not be outsized. Overlaid was confirmation from the corporate bond market as spreads on high yield bonds, CLOs and other structured products began to narrow in the second quarter of 2020 as banks were still building reserves.

As of October 28, 2020, the NASDAQ Bank Index has risen 78% over the past year and 39% year-to-date.

Much of that gain occurred during November (October 2020 was a strong month, too) through May as investors initially priced-in reserve releases to come; and then NIMs that might not fall as far as feared as the yield on the 10-year UST doubled to 1.75% by late March. Bank stocks underperformed the market during the summer as the 10-year UST yield fell. Since late September banks rallied again as investors began to price rate hikes by the Fed beginning in 2022 rather than 2023.

No one knows for sure; the future is always uncertain. For banks, two key variables have an outsized influence on earnings other than credit costs: loan demand and rates. In other industries the variables are called volume and price. If both rise, most banks will see a pronounced increase in earnings as revenues rise and presumably operating leverage improves. Street estimates for 2022 and 2023 will rise, and investors’ view of earning power will too.

We do not know what the future will be either. Loan demand and excess liquidity have been counter cyclical forces in the banking industry since banks came into being. The question is not if but how strong loan demand will be when the cycle turns. Interest rates used to be cyclical, too, until governments became so indebted that “normal” rates apparently cannot be tolerated.

Nonetheless, at Mercer Capital we have decades of experience of evaluating earnings, earning power, multiples and other value drivers. Please give us a call if we can assist your institution.

Meet the Team – Karolina Calhoun, CPA/ABV/CFF

In each “Meet the Team” segment, we highlight a different professional on our Family Law team. The experience and expertise of our professionals allow us to bring a full suite of valuation and forensics services to our clients. We hope you enjoy getting to know us a bit better.

Tell us a little about your career and what influenced your “return” to Mercer Capital.

Karolina Calhoun: During my college experience at Rhodes College, I interned at Mercer Capital, Morgan Keegan (now known as Raymond James) in investment banking and then another internship in wealth management, and ALSAC/St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. I also interned internationally with Ernst and Young (EY) in Warsaw, Poland, which is where I was born and have many family members that still live there.

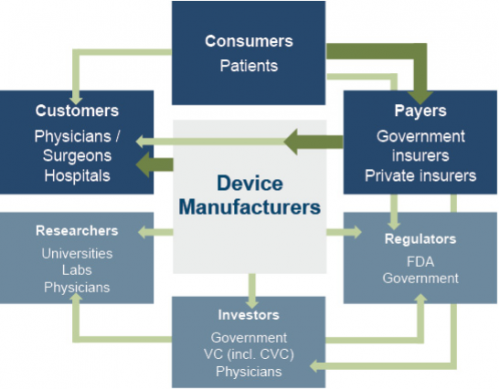

After graduating from Rhodes College, I completed my Master of Accountancy and CPA accreditation. I started working for EY in their Audit and Assurances department. During my 3+ years at EY, I had the opportunity to work with Fortune 500 clients, as well as other sized companies in diverse industries such as chemical and agriculture, logistics, medical devices, healthcare, and wealth management and investment management. At the time that I came back to Mercer Capital, I was ready to take my public accounting knowledge and experience and pivot to finance-related client work.

How does your Big 4 public accounting background assist you and your clients in a litigation matter?

Karolina Calhoun: The knowledge of accounting and financial reporting is important. It helps me quickly understand the financial statements of businesses, personal financial statements, and tax returns, among other financial documents. My auditing experience was investigative in a sense, so I have a good idea of what to look for and other red flags. Additionally, from a client perspective, individuals and attorneys tend to trust a CPA’s professional expertise in litigation cases, especially in specialized areas like valuation and forensics. My additional credentials, the ABV and CFF, further bolster the expertise I can offer clients.

You’re involved with the AICPA Forensics & Valuation Services Section. Can you tell us more about this organization and your involvement?

Karolina Calhoun: I am so thankful for the national and global opportunities/positions I hold now with the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). I am serving as the Valuation Chair of the AICPA Forensic and Valuation Services (FVS) Conference and I also serve on the CFF Exam Task Force. My committee and task force positions have provided me the opportunities to be involved with thought leaders across the globe and assist our evolving profession. During my tenure so far, I have met and collaborated with many colleagues from all over the United States and beyond North America.

I became involved with the AICPA FVS Section at an early point in my career at Mercer Capital. I attended the NextGen training program, which is catered towards rising leaders in the FVS profession. After meeting and networking with AICPA staff and volunteers, I applied to be considered for future volunteer opportunities. I was so excited when I was invited to join the AICPA Forensics & Valuation Services Conference Planning Committee. Then, in 2019 I was asked to be the 2020 & 2021 Valuation Chair. In this position, I am integral in leading the Committee’s efforts in planning our annual conference, selecting topics, inviting speakers, and collaborating with the AICPA staff & speakers.

In my role on the CFF Exam Task Force, I am contributing to the efforts to pivot the CFF (Certified in Financial Forensics) accreditation towards a universal body of knowledge and examination process. Our committee evaluated the existing test bank of questions and rewrote and wrote new questions to comply with our global framework. As I mentioned earlier, I was born in Poland and interned abroad, so I love being a part of this global initiative as our profession continues to evolve.

How meaningful is it for the Litigation Services Group to offer both valuation & forensic services?

Karolina Calhoun: During my tenure at Mercer Capital, as a CPA with an interest in finance, valuation, and forensic accounting, I have helped establish the Litigation Services Group at Mercer Capital. We have extended our services beyond valuation and financial consulting to also encompass forensic services. I think it is very valuable to be able to provide a full suite of services as oftentimes, valuation and forensic services are interconnected.

Take a divorce litigation for example. Historically, Mercer Capital would be called for the valuation of a business, and an external forensic accountant would provide the lifestyle analysis and other forensic needs. However, now Mercer Capital can assist with both the valuation and forensic scope of that divorce engagement. Extending beyond divorce litigation, our team provides valuation, forensic accounting, and financial consulting for a variety of engagements: business damages, lost profits, shareholder disputes, breach of contract, trademark infringement, and estate and tax planning, among others.

What drew you to financial forensics and in what ways are Mercer Capital professionals skilled for these types of litigation matters?

Karolina Calhoun: I enjoy the combination of accounting, economics, finance, and forensics. Litigation services is a field where we have to put all of these skills together and evaluate the facts and circumstances unique to the particular matter(s) at hand – no fact pattern is ever the same. Our Litigation Services Group at Mercer Capital is comprised of qualified professionals who have the necessary skills and experience in accounting, finance, and economics and in a wide variety of industries and types of matters.

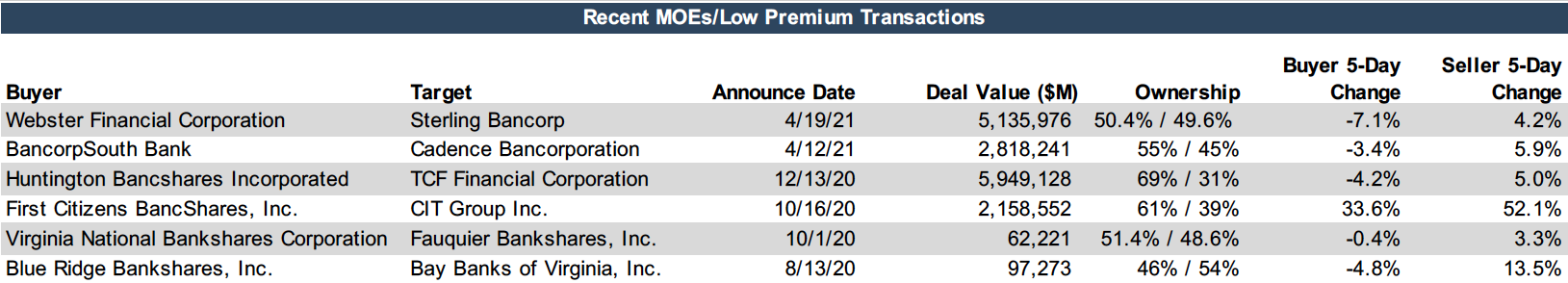

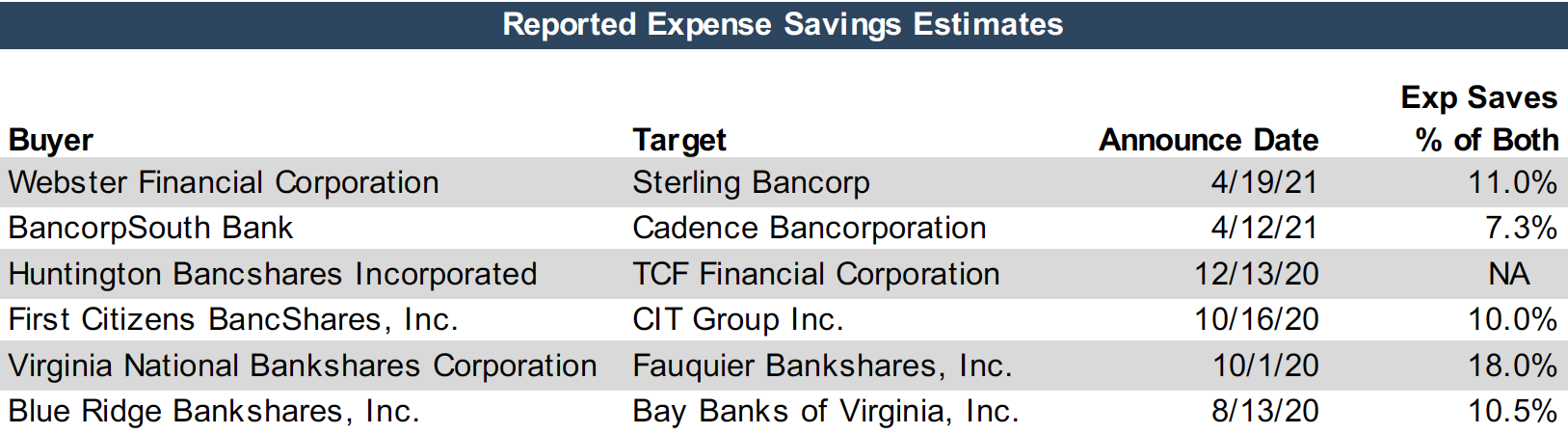

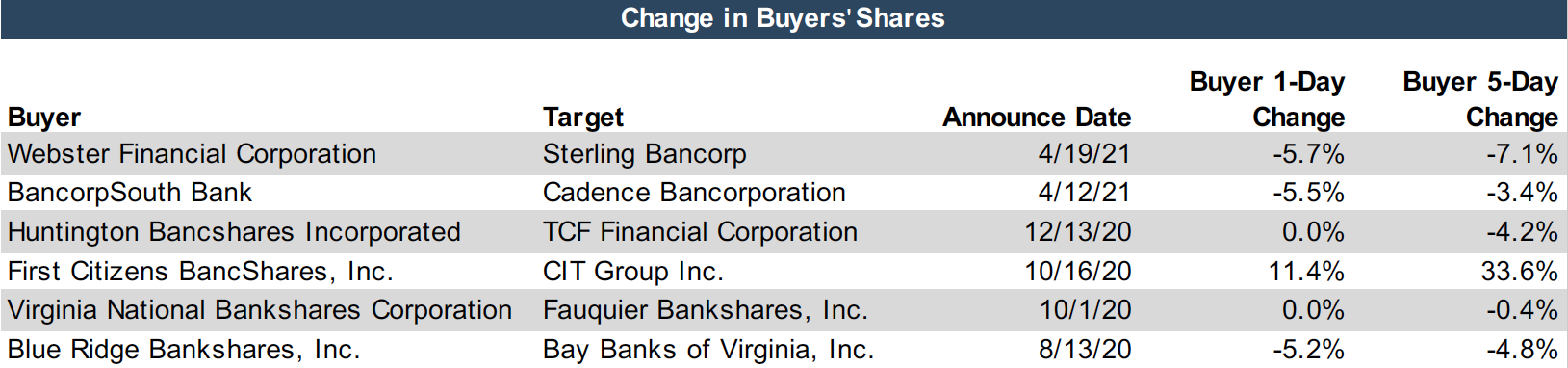

Fairness Opinions – Evaluating a Buyer’s Shares from the Seller’s Perspective

Depository M&A activity in the U.S. has accelerated in 2021 from a very subdued pace in 2020 when uncertainty about the impact of COVID-19 and the policy responses to it weighed on bank stocks. At the time, investors were grappling with questions related to how high credit losses would be and how far would net interest margins decline. Since then, credit concerns have faded with only a nominal increase in losses for many banks. The margin outlook remains problematic because it appears unlikely the Fed will abandon its zero-interest rate policy (“ZIRP”) anytime soon.

As of September 23, 2021, 157 bank and thrift acquisitions have been announced, which equates to 3.0% of the number of charters as of January 1. Assuming bank stocks are steady or trend higher, we expect 200 to 225 acquisitions this year, equivalent to about 4% of the industry and in-line with 3% to 5% of the industry that is acquired in a typical year. During 2020, only 117 acquisitions representing 2.2% of the industry were announced, less than half of the 272 deals (5.0%) announced in pre-covid 2019.

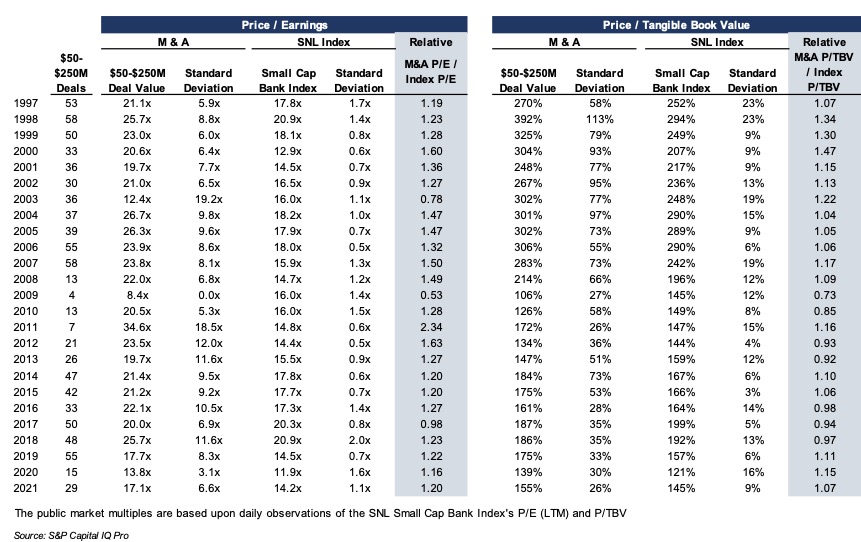

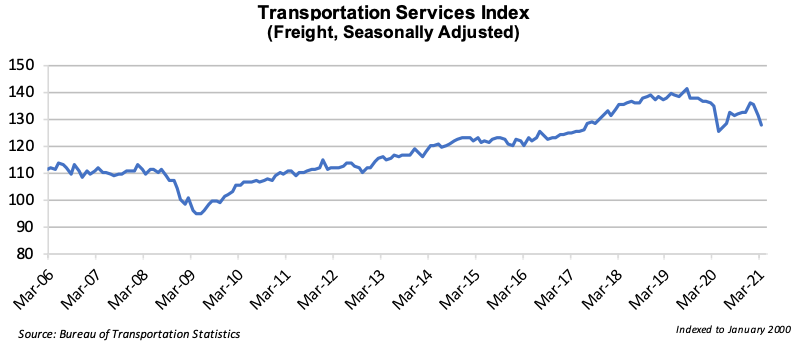

To be clear, M&A activity follows the public market, as shown in Figure 1. When public market valuations improve, M&A activity and multiples have a propensity to increase as the valuation of the buyers’ shares trend higher. When bank stocks are depressed for whatever reason, acquisition activity usually falls, and multiples decline.

Click here to expand the image above

The rebound in M&A activity this year did not occur in a vacuum. Year-to-date through September 23, 2021, the S&P Small Cap and Large Cap Bank Indices have risen 25% and 31% compared to 18% for the S&P 500. Over the past year, the bank indices are up 87% and 79% compared to 37% for the S&P 500.

Excluding small transactions, the issuance of common shares by bank acquirers usually is the dominant form of consideration sellers receive. While buyers have some flexibility regarding the number of shares issued and the mix of stock and cash, buyers are limited in the amount of dilution in tangible book value they are willing to accept and require visibility in EPS accretion over the next several years to recapture the dilution.

Because the number of shares will be relatively fixed, the value of a transaction and the multiples the seller hopes to realize is a function of the buyer’s valuation. High multiple stocks can be viewed as strong acquisition currencies for acquisitive companies because fewer shares are issued to achieve a targeted dollar value.

However, high multiple stocks may represent an under-appreciated risk to sellers who receive the shares as consideration. Accepting the buyer’s stock raises a number of questions, most which fall into the genre of: what are the investment merits of the buyer’s shares? The answer may not be obvious even when the buyer’s shares are actively traded.

Our experience is that some, if not most, members of a board weighing an acquisition proposal do not have the background to thoroughly evaluate the buyer’s shares. Even when financial advisors are involved, there still may not be a thorough vetting of the buyer’s shares because there is too much focus on “price” instead of, or in addition to “value.”

A fairness opinion is more than a three or four page letter that opines as to the fairness from a financial point of a contemplated transaction; it should be backed by a robust analysis of all of the relevant factors considered in rendering the opinion, including an evaluation of the shares to be issued to the selling company’s shareholders. The intent is not to express an opinion about where the shares may trade in the future, but rather to evaluate the investment merits of the shares before and after a transaction is consummated.

Key questions to ask about the buyer’s shares include the following:

Liquidity of the Shares – What is the capacity to sell the shares issued in the merger? SEC registration and NASADQ and NYSE listings do not guarantee that large blocks can be liquidated efficiently. OTC traded shares should be scrutinized, especially if the acquirer is not an SEC registrant. Generally, the higher the institutional ownership, the better the liquidity. Also, liquidity may improve with an acquisition if the number of shares outstanding and shareholders increase sufficiently.

Profitability and Revenue Trends – The analysis should consider the buyer’s historical growth and projected growth in revenues, pretax pre-provision operating income and net income as well as various profitability ratios before and after consideration of credit costs. The quality of earnings and a comparison of core vs. reported earnings over a multi-year period should be evaluated. This is particularly important because many banks’ earnings in 2020 and 2021 have been supported by mortgage banking and PPP fees.

Pro Forma Impact – The analysis should consider the impact of a proposed transaction on the pro forma balance sheet, income statement and capital ratios in addition to dilution or accretion in earnings per share and tangible book value per share both from the seller’s and buyer’s perspective.

Tangible BVPS Earn-Back – As noted, the projected earn-back period in tangible book value per share is an important consideration for the buyer. In the aftermath of the GFC, an acceptable earn back period was on the order of three to five years; today, two to three years may be the required earn-back period absent other compelling factors. Earn-back periods that are viewed as too long by market participants is one reason buyers’ shares can be heavily sold when a deal is announced that otherwise may be compelling.

Dividends – In a yield starved world, dividend paying stocks have greater attraction than in past years. Sellers should not be overly swayed by the pick-up in dividends from swapping into the buyer’s shares; however, multiple studies have demonstrated that a sizable portion of an investor’s return comes from dividends over long periods of time. Sellers should examine the sustainability of current dividends and the prospect for increases (or decreases). Also, if the dividend yield is notably above the peer average, the seller should ask why? Is it payout related, or are the shares depressed?

Capital and the Parent Capital Stack – Sellers should have a full understanding of the buyer’s pro-forma regulatory capital ratios both at the bank-level and on a consolidated basis (for large bank holding companies). Separately, parent company capital stacks often are overlooked because of the emphasis placed on capital ratios and the combined bank-parent financial statements. Sellers should have a complete understanding of a parent company’s capital structure and the amount of bank earnings that must be paid to the parent company for debt service and shareholder dividends.

Loan Portfolio Concentrations – Sellers should understand concentrations in the buyer’s loan portfolio, outsized hold positions, and a review the source of historical and expected losses.

Ability to Raise Cash to Close – What is the source of funds for the buyer to fund the cash portion of consideration? If the buyer has to go to market to issue equity and/or debt, what is the contingency plan if unfavorable market conditions preclude floating an issue?

Consensus Analyst Estimates – If the buyer is publicly traded and has analyst coverage, consideration should be given to Street expectations vs. what the diligence process determines. If Street expectations are too high, then the shares may be vulnerable once investors reassess their earnings and growth expectations.

Valuation – Like profitability, valuation of the buyer’s shares should be judged relative to its history and a peer group presently and relative to a peer group through time to examine how investors’ views of the shares may have evolved through market and profit cycles.

Share Performance – Sellers should understand the source of the buyer’s shares performance over several multi-year holding periods. For example, if the shares have significantly outperformed an index over a given holding period, is it because earnings growth accelerated? Or, is it because the shares were depressed at the beginning of the measurement period? Likewise, underperformance may signal disappointing earnings, or it may reflect a starting point valuation that was unusually high.

Strategic Position – Assuming an acquisition is material for the buyer, directors of the selling board should consider the strategic position of the buyer, asking such questions about the attractiveness of the pro forma company to other acquirers?

Contingent Liabilities – Contingent liabilities are a standard item on the due diligence punch list for a buyer. Sellers should evaluate contingent liabilities too.

The list does not encompass every question that should be asked as part of the fairness analysis, but it does illustrate that a liquid market for a buyer’s shares does not necessarily answer questions about value, growth potential and risk profile. The professionals at Mercer Capital have extensive experience in valuing and evaluating the shares (and debt) of financial and non-financial service companies garnered from over three decades of business. Give us a call to discuss your needs in confidence.

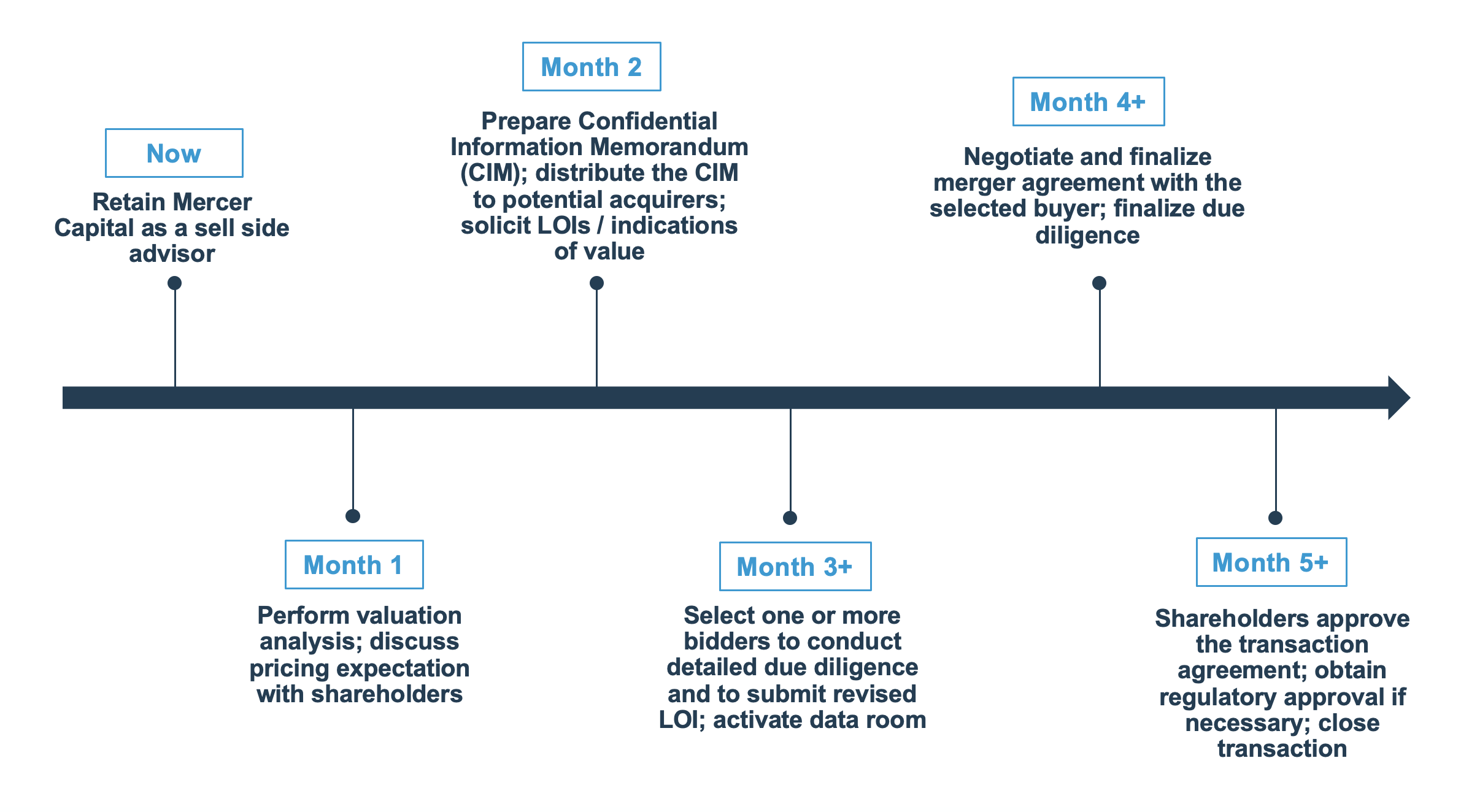

Three Considerations Before You Sell Your Business

After spending years, if not decades, building your business through hard work, determination, and a little luck, what happens when you are ready to monetize your efforts by selling part or all of your business? Exiting the business you built from the ground up is often a bittersweet experience. Many business owners focus their efforts on growing their business and push planning for their eventual exit aside until it can’t be ignored any longer. However, long before your eventual exit, you should begin planning for the day you will leave the business you built.

We suggest you consider these three things.

1. Have a Reasonable Expectation of Value

Many business owners have difficulty taking an objective view of the value of their company. In many cases, it becomes a highly emotional issue, which is certainly understandable considering that many business owners have spent most of their adult lives operating and growing their companies. Nevertheless, the development of reasonable pricing expectations is a vital starting point on the road to a successful transaction.

The development of pricing expectations for an external sale should consider how a potential acquirer would analyze your company. In developing offers, potential acquirers can (and do) use various methods to develop a reasonable purchase price. An acquirer will utilize historical performance data, along with expectations for the future, to develop a level of cash flow or earnings that is considered sustainable going forward. In most cases, this analysis will focus on earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA) or some other pre-interest cash flow. A multiple is applied to this sustainable cash flow to provide an indication of value for the company. Multiples are developed based on an assessment of the underlying risk and growth factors of the subject company.

Valuations and financial analysis for transactions encompass a refined and scenario-specific framework. The valuation process should enhance a buyer’s understanding of the cash flows and corresponding returns that result from purchasing or investing in a firm. For sellers or prospective sellers, valuations and exit scenarios can be modeled to assist in the decision to sell now or later and to assess the adequacy of deal consideration. Setting expectations and/or defining deal limitations are critical to good transaction discipline.

2. Consider the Tax Implications

When analyzing the net proceeds from a transaction, you must consider the potential tax implications. From simple concepts such as ordinary income vs. capital gains and asset sales vs. stock sales, to more nuanced concepts such as depreciation recapture and purchase price allocation, there are almost unlimited issues that can come up related to the taxation of transaction proceeds. The structure of your own corporate entity (C Corporation vs. tax-pass through entity) may have a material impact on the level of taxes owed from a potential transaction.

We recommend consulting with your outside accountant (or hiring a tax attorney) early in the process of investigating a transaction. Only a tax specialist can provide the detailed advice that is needed regarding the tax implications of different transaction structures. There could be strategies that can be implemented well in advance of a transaction to better position your business or business interest for an eventual transaction.

3. Have a Real Reason to Sell Your Business

Strategy is often discussed as something belonging exclusively to buyers in a transaction. Not true.

Sellers need a strategy as well: what’s in it for you? Sellers often feel like all they are getting is an accelerated payout of what they would have earned anyway while giving up their ownership. In many cases, that’s exactly right! Your Company, and the cash flow that creates value, transfers from seller to buyer when the ink dries on the purchase agreement. Sellers give up something equally valuable in exchange for purchase consideration – that’s how it works.

As a consequence, sellers need a real reason – a non-financial strategic reason – to sell. Maybe you are selling because you want or need to retire. Maybe you are selling because you want to consolidate with a larger organization, or need to bring in a financial partner to diversify your own net worth and provide ownership transition to the next generation. Whatever the case, you need a real reason to sell other than trading future compensation for a check. The financial trade won’t be enough to sustain you through the twists and turns of a transaction.

The process of selling a business is typically one of the most important, and potentially complex, events in an individual’s life. Important decisions such as this are best made after a thorough consideration of the entire situation. Early planning can often be the difference between an efficient, controlled sales process and a rushed, chaotic process.

Mercer Capital provides transaction advisory services to a broad range of public and private companies and financial institutions. We have assisted hundreds of companies with planning and executing potential transactions since Mercer Capital was founded in 1982. Rather than pushing solely for the execution of any transaction, Mercer Capital positions itself as an advisor, encouraging the right decision to be made by its clients.

Our dedicated and responsive team is available to advise you through a transaction process, from initial planning and investigation through eventual execution. To discuss your situation in confidence, give us a call.

Valuations for Gift & Estate Tax Planning

Managing Complicated Multi-Tiered Entity Valuation Engagements

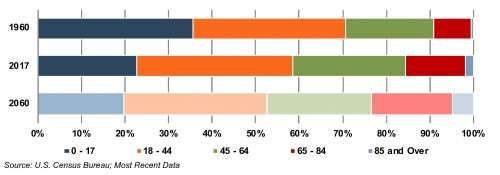

When equity markets fell in early 2020 due to the onset of the COVID-19 global pandemic, many business owners and tax planners contemplated whether it was an opportune time to engage in significant ownership transfers. Although equity markets have recovered to all-time highs, a confluence of three factors may make 2021 an ideal time for estate planning transactions for owners of private companies:

- Depressed Valuations. Valuations for many privately held businesses remain somewhat depressed due to significant supply chain challenges and hiring difficulties.

- Low Interest Rates. Applicable federal rates (AFRs) are at historically low levels, allowing business owners to make leveraged estate planning strategies more efficient.

- Political Risk. The Biden administration’s proposal to lower the gift and estate tax exemption and increase the capital gains tax rate may prompt some individuals and businesses to take advantage of currently favorable tax conditions before any adverse changes are made.

Mercer Capital has been performing valuations for complicated tax engagements since its inception in 1982. For many high net worth individuals and family offices, complex ownership structures have evolved over time, typically involving multi-tiered entity organizations and businesses with complicated ownership structures and governance. In this article, we describe the processes that lead to credible and timely valuation reports. These processes contribute to smoother engagements and better outcomes for clients.

Defining the Engagement

Defining the valuation project is an important step in every engagement process, but when multiple or tiered entities are involved, it becomes critical. It is insufficient to define a complicated engagement by referring only to the top tier entity in a multi-tiered organizational structure. The engagement scope should clearly identify all the direct and indirect ownership interests that will need to be valued. This allows the appraiser to plan the underlying due diligence and analytical framework to design the deliverable work product.

For example, will the appraiser need to perform a separate appraisal at each level of a tiered structure? Or, can certain entities or underlying assets be valued using a consolidated analytical framework? Planning well on the front end of an engagement leads to more straightforward analyses that are easier to defend.

Collecting the Necessary Information

During the initial discussion of the engagement, the appraiser will usually request certain descriptive and financial information (such as governing documents, recent audits, compilations, and/or tax returns) to determine the scope of analysis needed to render a credible appraisal for the master, top-tier entity and the underlying entities and assets.

Upon being retained, one of the first things an appraiser will do is to prepare a more comprehensive information request list designed to solicit all the documentation necessary to render a valuation opinion. Full and complete disclosure of all requested information, as well as other information believed pertinent to the appraisal, will aid the appraiser in preventing double-counting or otherwise missing assets all together.

Information Needed for Complex Multi-Tiered Entity Valuation

Requested information for complex multi-tiered entity valuations typically falls into three

broad categories:

- Legal documentation. The legal structure and inter-relationships in complex assignments are essential to deriving reliable valuation conclusions. In addition to the operating agreements, it is important to have current shareholder/member lists. A graphical organization chart is often a very helpful supplement to the legal documents and helps ensure that everyone really is “on the same page” regarding the objectives of the valuation assignment.

- Financial statements. A careful review of the historical financial statements for each entity in the overall structure provides essential context for the cash flow projections, growth outlook, and risk assessment that are the basic building blocks for any valuation assignment. Depending on ownership characteristics and business attributes, it may be appropriate to combine financial statements for multiple entities to promote efficiency in project execution.

- Supplementary information. For operating businesses, supplementary information may include financial projections, detailed revenue and margin data (by customer, product, region or some other basis), personnel information, and/or information pertaining to the competitive environment. For asset-holding entities, supplementary data may include current appraisals of real estate or other illiquid underlying assets, brokerage statements, and the like.

The ultimate efficiency of the project often hinges on timely receipt of all requested information. Disorganized information or data that requires a lot of handling or interpretation on the part of the appraiser adds to project cost, and more importantly, can make it harder to defend valuation conclusions that are later subject to scrutiny.

In short, providing high quality information in response to the appraiser’s request list promotes a more predicable outcome with the IRS and with other stakeholders.

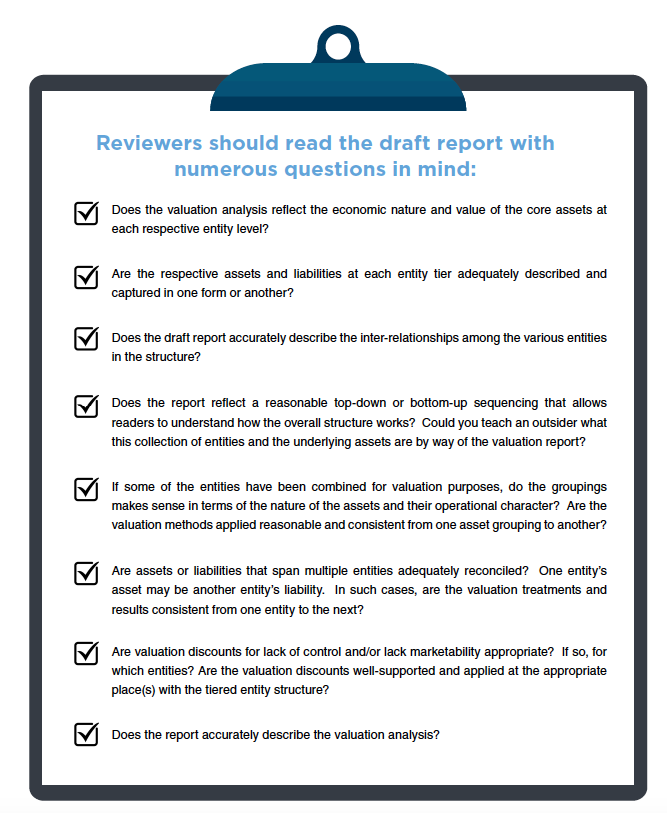

The Importance of Reviewing the Draft Appraisal

Upon completing research, due diligence interviews with appropriate parties, and the valuation analysis, the appraiser should provide a draft appraisal report for review. The steps discussed thus far – careful planning and timely information collection – are not substitutes for careful review of the draft appraisal report. The complexity of many multi-tiered structures increases the need for relevant parties to review the draft appraisal for completeness and factual accuracy.

Engagements involving complicated entity and operational structures are not easily shoehorned into typical appraisal reporting formats and presentation. Unique entity and asset attributes may require complex valuation techniques and heighten the need for clear and concise reporting of appraisal results. Regardless of the

complexity of the underlying structure and valuation techniques, the appraisal report should still be easy to read and understand.

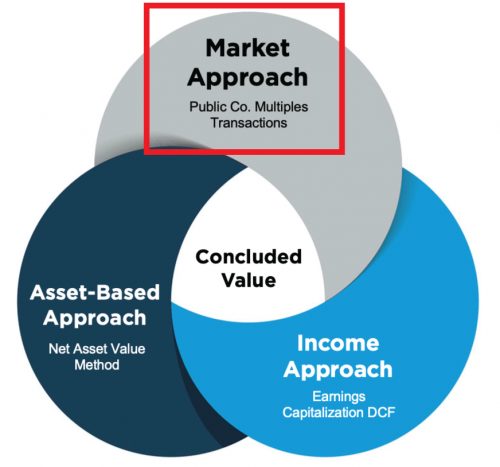

Understand the Income Approach in a Business Valuation

What Is the Income Approach and How Is It Utilized?

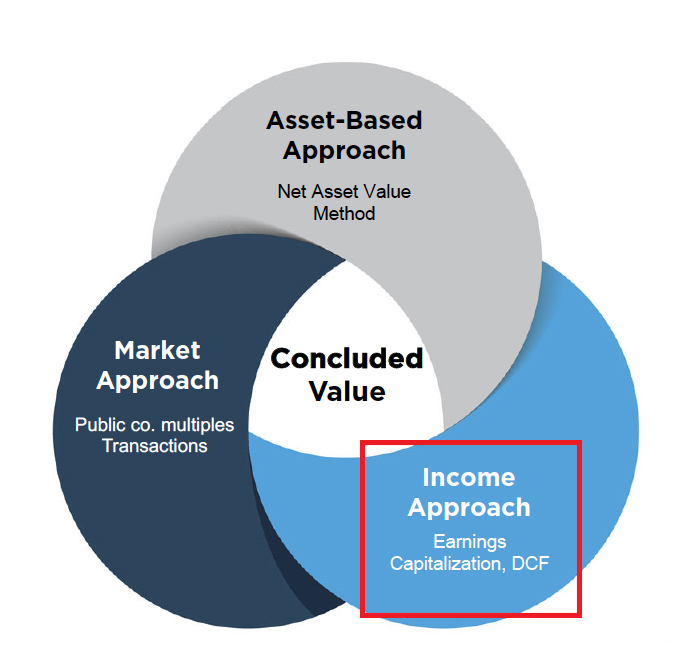

We recently wrote about the market approach, which is one of the three primary approaches utilized in business valuations. In this article, we’ll be presenting a broad overview of the income approach. The final approach, the asset-based approach, will discussed in a future article. While each approach should be considered, the approach(es) ultimately relied upon will depend on the unique facts and circumstances of each situation.

The income approach is a general way of determining the value of a business by converting anticipated economic benefits into a present single amount. Simply put, the value of a business is directly related to the present value of all future cash flows that the business is reasonably expected to produce. The income approach requires estimates of future cash flows and an appropriate rate at which to discount those future cash flows.

Methods under the income approach are varied but typically fall into one of two categories:

- Single period methods, for example capitalization of earnings or free cash flow

- Multi-period methods like the discounted cash flow (DCF)

The question if often asked, which method should you use, or should you use multiple methods? Also, does one use single period methods, or multi-period method? It depends on the facts and circumstances, including but not limited to, whether the business is in a mature or growing business cycle, if budgets/projections are prepared in normal course of business, among other considerations. More importantly, the analyst must evaluate if trends analyzed from the business’ historical performance provide a reasonable indication of the future, and which methodology or methodologies best capture that future economic stream of benefits.

Normalizing Adjustments

Before analyzing each method, it is important to start with normalizing adjustments, which serve as a foundation for both income approach methodologies. Normalizing adjustments adjust the income statement of a private company to show the financial results from normal operations of the business and reveal a “public equivalent” income stream. In creating a public equivalent for a private company, another name given to the marketable minority level of value is “as if freely traded,” which emphasizes that earnings are being normalized to where they would be as if the company were public, hence supporting the need to carefully consider and apply, when necessary, normalizing adjustments. There are two categories of adjustments.

Non-Recurring, Unusual Items

Mercer Capital dives deep into this subject in this article, but here are some highlights. These adjustments eliminate one-time gains or losses, unusual items, non-recurring business elements, income/expenses of non-operating assets, and the like. Examples include, but are not limited to:

- One-time legal settlement. The income (or loss) from a non-recurring legal settlement would be eliminated and earnings would be reduced (or increased) by that amount.

- Gain from sale of asset. If an asset that is no longer contributing to the normal operations of a business is sold, that gain would be eliminated and earnings reduced.

- Life insurance proceeds. If life insurance proceeds were paid out, the proceeds would be eliminated as they do not recur, and thus, earnings are reduced. The balance sheet impact can be dependent on whether the company has a direct obligation to repurchase the shares or not.

- Restructuring costs. Sometimes companies must restructure operations or certain departments, the costs are one-time or rare, and once eliminated, earnings would increase by that amount.

Discretionary Items

These adjustments relate to discretionary expenses paid to or on behalf of owners of private businesses. Examples include the normalization of owner/officer compensation to comparable market rates, as well as elimination of certain discretionary expenses, such as expenses for non-business purpose items (lavish automobiles, boats, planes, personal living expenses, etc.) that would not exist in a publicly traded company.

For more, refer to our article “Normalizing Adjustments to the Income Statements” and Chris Mercer’s blog.

Single Period Capitalization Method

Once the analyst determines adjusted earnings, we can move forward to capitalizing these economic benefits.

The simplest method used under the income approach is a single period capitalization model. Ultimately, this method is an algebraic simplification of its more detailed DCF counterpart. As opposed to a detailed projection of future cash flow, a base level of annual net cash flow and a sustainable growth rate are determined.

The value of any operating asset/investment is equal to the present value of its expected future economic benefit stream.

If the growth in cash flows is constant, this can be simplified:

Where

CF = Next year’s cash flow

g = perpetual growth rate

r = discount rate for projected cash flows

The denominator of the expression on the right (r – g) is referred to as the “capitalization rate,” and its reciprocal is the familiar “multiple” that is applicable to next year’s cash flow. The multiple (and thus the firm’s value) is negatively correlated to risk and positively correlated to expected growth. There are two primary methods for determining an appropriate capitalization rate—a public guideline company analysis or a “build-up” analysis (previous article by Mercer Capital where we discussed the discount rate in detail).

Discounted Cash Flow Method

Businesses may be valued using the DCF method because this method allows for modeling of varying or near-term accelerated growth revenues, expenses, and other sources and uses of cash over a discrete projection period. Beyond the discrete projection period, it is assumed that the business will grow at a constant rate into perpetuity. As that point, the future beyond the projection period is capitalized as the terminal value and the method converges to the single period capitalization.

In circumstances where no changes in the business model or capital structure are expected, a single period capitalization method may be sufficient. Ultimately, the DCF’s output is only as good as its inputs, therefore, testing of assumptions and reasonableness is critical.

The discounted cash flow methodology requires assumptions, but the formula can be broken down to three basic elements:

- Projected future cash flows

- Discount rate

- Terminal value

Projected Future Cash Flows

Discrete cash flows are forecasted for as many periods as necessary until a stabilized earnings stream could be anticipated (commonly in the range of 3-10 years). Ideally, projections will be sourced from management, but if management projections are not available, a competent valuation professional may choose to develop a forecast based on historical performance, industry data, and discussions with management. It is important to test the reasonableness of the projections by comparing historical and projected performance as well as expectations based on the subject company’s history and the industry in which it operates.

Discount Rate

A discount rate is used to convert future cash flows to present value as of the valuation date. Factors to consider include, but are not limited to business risk, supplier and/or customer concentrations, market and industry risk, size of the company, financial leverage, capital structure, among others. For a detailed look into discount rates, see a recent article published by Mercer Capital.

Terminal Value

The terminal value captures the value of the company into perpetuity. It uses a terminal growth rate, the discount rate, and the final year cash flow to arrive at a value, which is discounted and added to the discrete cash flow projections.

Conclusion

The income approach can determine the value of an operating business using financial metrics, growth rate and discount rate unique to the subject company. However, each method within the income approach must be selected based on applicability and facts and circumstances unique to the matter at hand; thus, a competent valuation expert is needed to ensure that the methods are applied in a thoughtful and appropriate manner.

Cash-Out Transactions and SEC Amended Rule 15c2-11

It may seem an odd time for some publicly traded companies to consider cash-out merger transactions because broad equity market indices are at or near record levels. Nonetheless, the changing market structure means some boards may want to consider it.

Among a small subset of public companies that may are those that are traded on OTC Markets Group’s Pink Open Market (“Pink”), the lowest of three tiers behind OTCQB Venture Market and OTCQX Best Market. Pink is the successor to the “pink sheets” which was published by a quotation firm that was purchased by investors who rechristened the firm OTC Markets Group.

Today, OTC Markets Group is an important operator in U.S. capital markets because it facilitates capital flows for 11,000 US and global securities that range from micro-cap and small-cap issuers across all major industries to ADRs of foreign large cap conglomerates. Many issuers are SEC registrants, too.

The issue that may cause some boards of companies traded on Pink to contemplate a cash-out merger or other transaction to reduce the number of shareholders is an amendment by the SEC to Rule 15c2-11, which governs the publication of OTC quotes and was last amended in 1991. Since then, markets and the public participation in markets have increased significantly as trading costs have declined and information has become more widely disseminated. The amendment applies only to Pink listed companies because those traded on OTCQB and OTCQX already meet the new requirements.

Because of a quirk in how the rule was written in conjunction with a “piggyback exception” for dealers, financial information for some Pink issuers is not publicly available. The amended rule, which goes into effect September 28, 2021, prohibits dealers from publishing quotes for companies that do not provide current information including balance sheets, income statements and retained earnings statements. OTC Markets Group requires companies to comply with the rule through posting information to the issuer’s publicly available landing page that it maintains.

While the disclosure requirement presumably is not burdensome, not all companies want to disclose such information, especially to competitors. Companies that choose not to comply with amended Rule 15c2-11 will no longer be eligible for quotation. Because shareholders of these companies historically have had the option to obtain liquidity, boards may want to evaluate an offer to repurchase shares or a cash-out merger transaction that reduces the number of shareholders.1

Also, some micro-cap and small-cap companies whether traded on an OTC market or a national exchange may not obtain as many advantages compared to a decade or so ago.

Given the rise of passive investing in which upwards of 50% of US equities are now held in a passively managed fund, companies that are not included in a major index such as the S&P 500, Russell 1000, NASDAQ or Russell 2000 are at a disadvantage given the amount of capital that now flows into passive funds. In some instances, it may make sense for these companies to go private, too.

Cash-out transactions can be particularly attractive for companies that have a high number of shareholders in which a small number of shareholders have substantial ownership. Cash-out merger transactions require significant planning with help from appropriate financial and legal advisors. The link here provides an overview of valuation and fairness issues to consider in going private and cash-out transactions for companies whether privately or publicly held.

Mercer Capital is a national valuation and financial advisory firm that works with companies, financial institutions, private equity and credit sponsors, high net worth individuals, benefit plan trustees, and government agencies to value illiquid securities and to provide financial advisory services related to M&A, divestitures, capital raises, buy-backs and other significant corporate transactions.

1 Cash-out merger transactions are also referred to as freeze-out mergers or squeeze-out mergers in shareholders owning fewer than a set number of shares receive cash for their shares while those holding more than the threshold amount will be continuing shareholders.

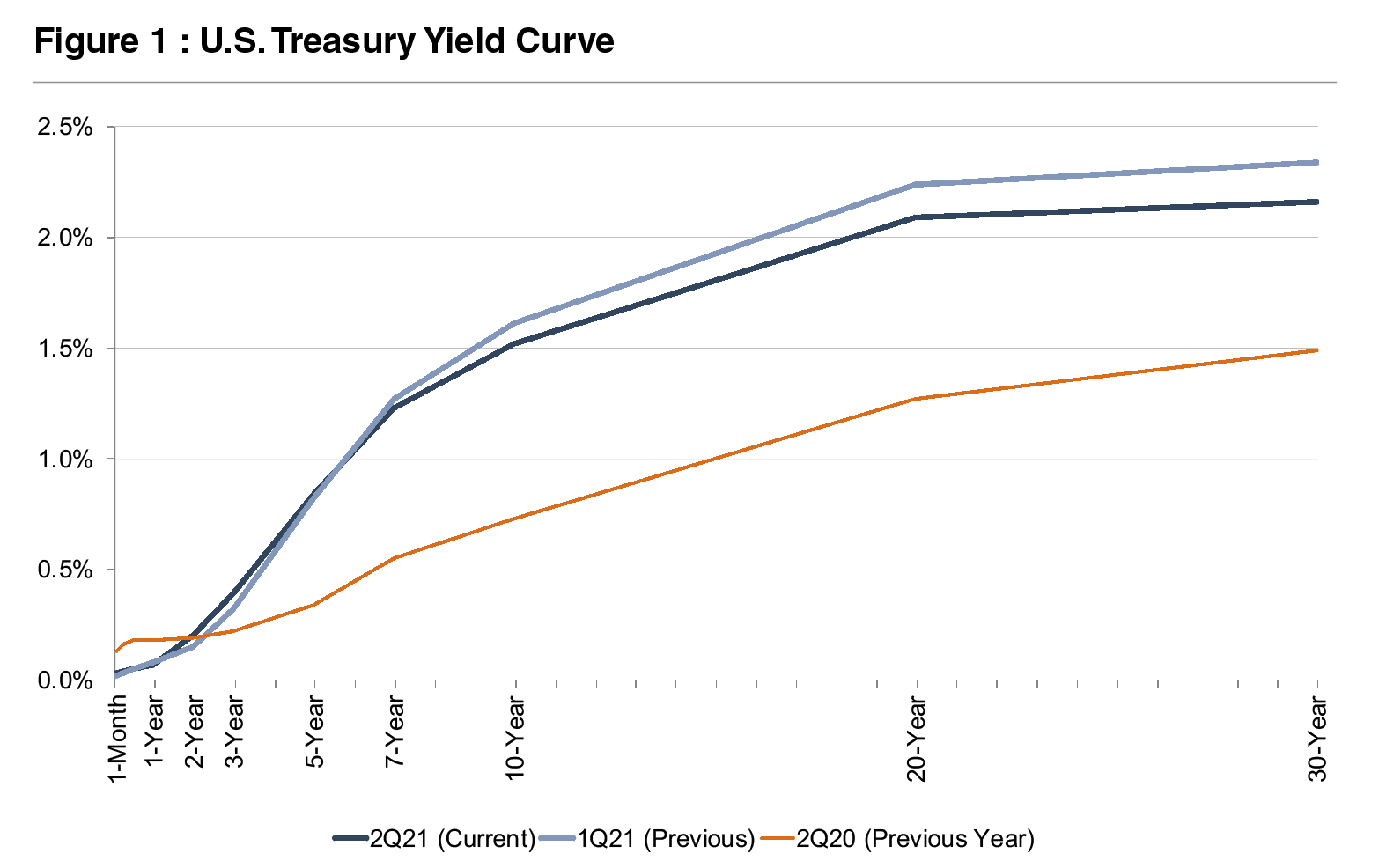

2021 Mid-Year Core Deposit Intangibles Update

In our last update regarding core deposit trends published in August 2020, we described a decreasing trend in core deposit intangible asset values in light of the pandemic. In response to the pandemic, the Fed cut rates to effectively zero, and the yield on the benchmark 10-year Treasury reached a record low. While many factors are pertinent to analyzing a deposit base, a significant driver of value is market interest rates. Although there has been some recovery in longer-term treasury rates since this time last year, shorter-term treasury rates (maturities of two years or less) have eased as investors concluded the Fed will not raise short-term policy rates in the near-term.

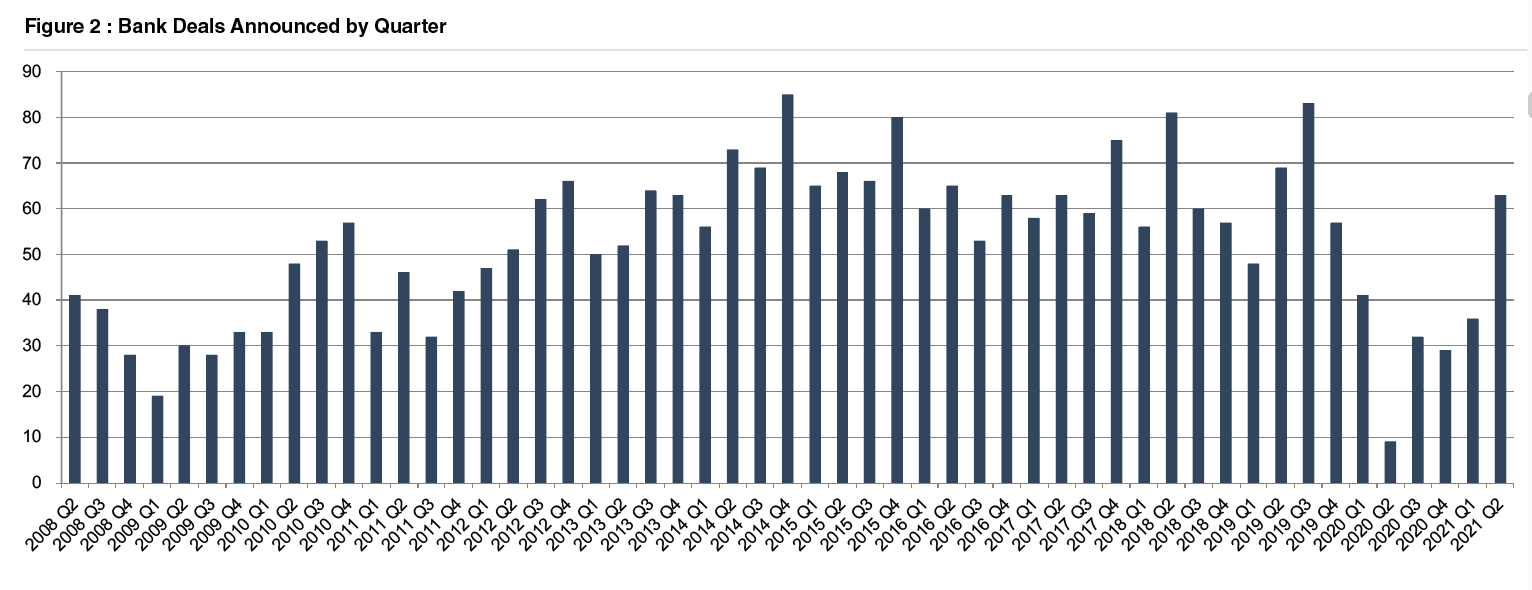

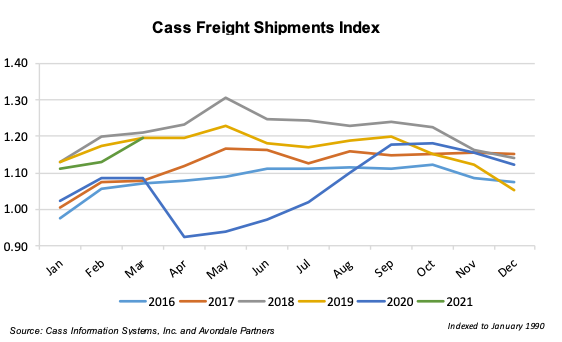

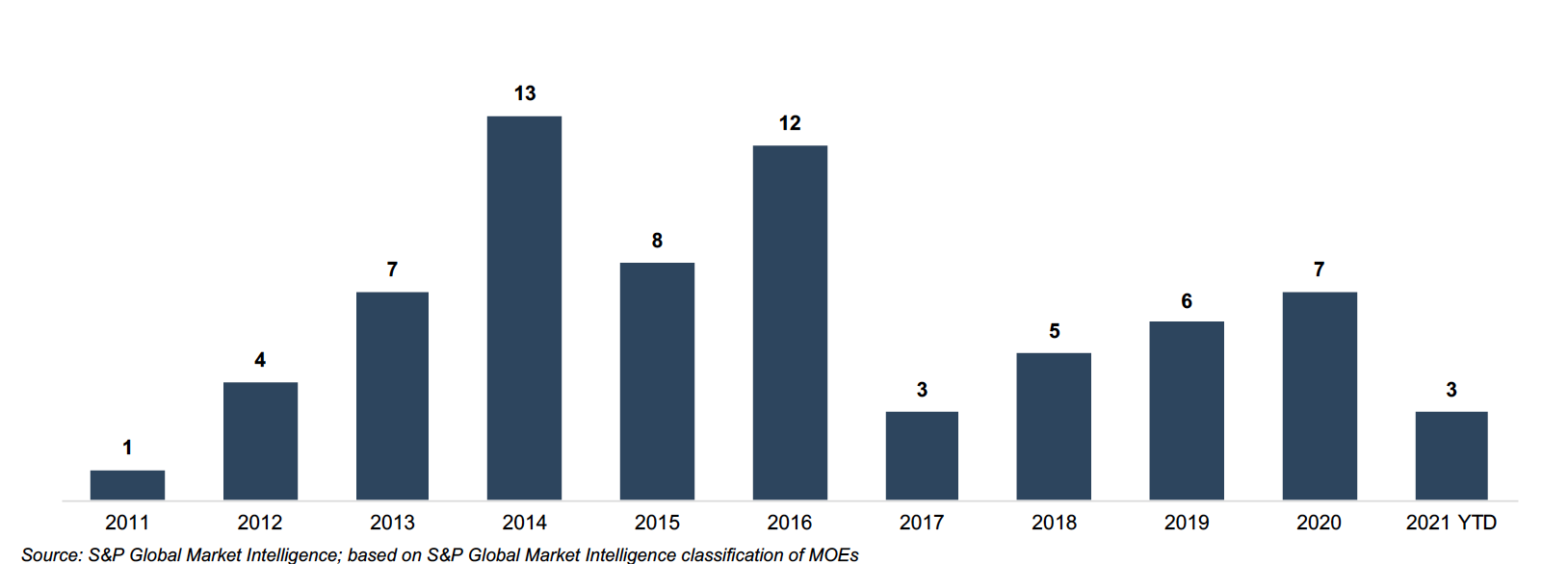

M&A Activity

For the full year of 2020, bank M&A activity fell sharply to 111 announced transactions from approximately 250 to 300 transactions per year during 2014 to 2019. More deals have been announced in the first eight months of 2021 than were announced in all of 2020. As shown in Figure 2, on the next page, the majority of the 2021 announcements occurred in the second quarter.

With 63 announced deals, the second quarter of 2021 represented the highest level of quarterly deal announcements since the third quarter of 2019 (83 deals). For comparison, only nine whole-bank transactions were announced in the second quarter of 2020, representing the fewest deals announced during a quarter over the time period analyzed. At this time last year, there were several factors hindering deal activity. Unknowns surrounding credit quality and the severity of loan deferrals in the midst of the pandemic gave pause to many deal talks in progress prior to the pandemic. Constraints surrounding travel and due diligence also hampered activity.

Ultimately, credit losses were not as significant as were feared initially, and travel has begun to normalize in the wake of widespread vaccine distribution. As a result, there appears to be a degree of pent-up demand in the bank M&A market. Moreover, many of the factors driving acquisitions have intensified over the past year.

Revenue pressure is causing institutions to seek operational efficiencies via synergies, as loan growth (excluding PPP loans) has been exceptionally weak over the past year, deposit growth has been unprecedented, and interest rates remain near historic lows. Additionally, as more consumers adopted digital banking in a socially-distancing society, banks lacking capability in this arena saw a more acute need to seek partnerships with more technologically advanced institutions.

Click here to expand the chart above

Trends In CDI Values

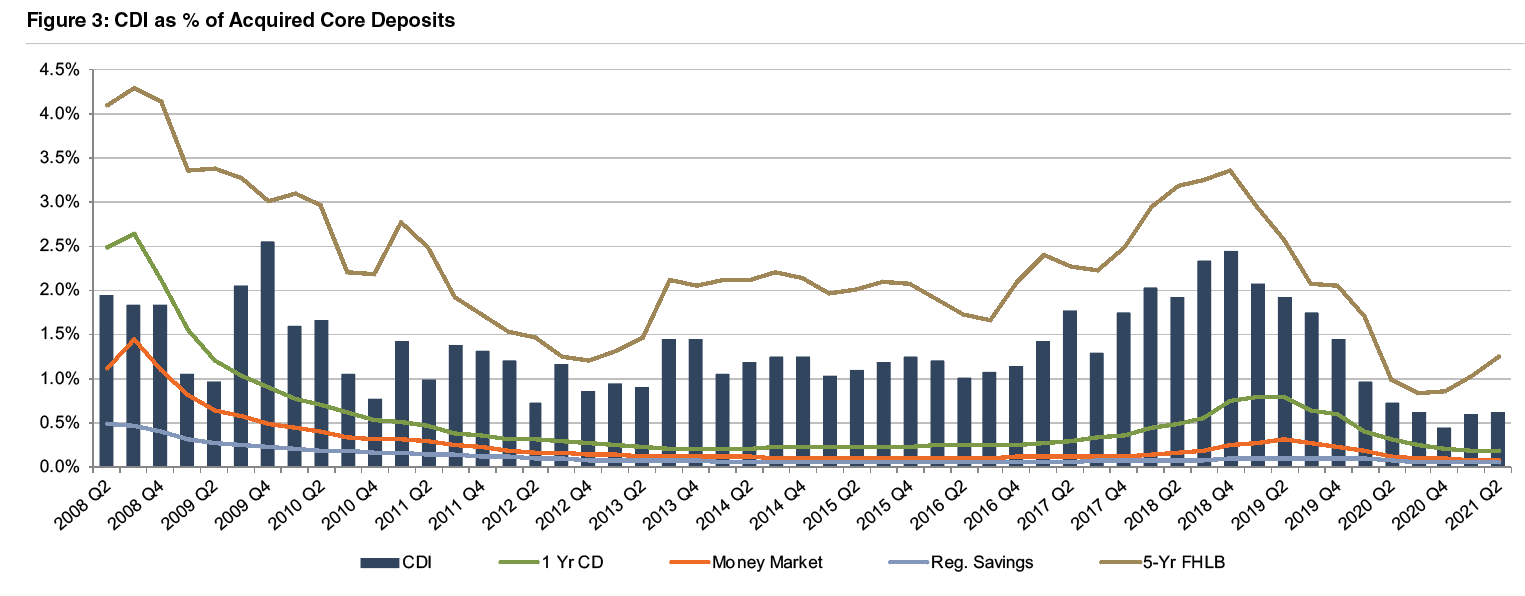

Using data compiled by S&P Capital IQ Pro, we analyzed trends in core deposit intangible (CDI) assets recorded in whole bank acquisitions completed from 2000 through June 30, 2021. CDI values represent the value of the depository customer relationships obtained in a bank acquisition. CDI values are driven by many factors, including the “stickiness” of a customer base, the types of deposit accounts assumed, and the cost of the acquired deposit base compared to alternative sources of funding. For our analysis of industry trends in CDI values, we relied on S&P Capital IQ Pro’s definition of core deposits.1 In analyzing core deposit intangible assets for individual acquisitions, however, a more detailed analysis of the deposit base would consider the relative stability of various account types.

In general, CDI assets derive most of their value from lower-cost demand deposit accounts, while often significantly less (if not zero) value is ascribed to more rate-sensitive time deposits and public funds, or to non-retail funding sources such as listing service or brokered deposits which are excluded from core deposits when determining the value of a CDI.

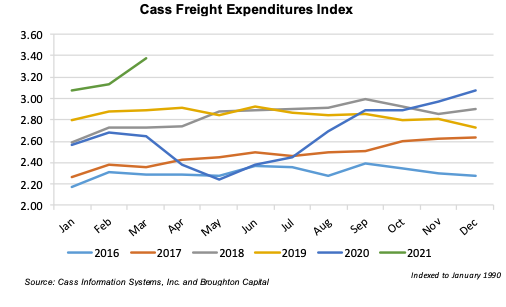

Figure 3, below, summarizes the trend in CDI values since the start of the 2008 recession, compared with rates on 5-year FHLB advances. Over the post-recession period, CDI values have largely followed the general trend in interest rates—as alternative funding became more costly in 2017 and 2018, CDI values generally ticked up as well, relative to post-recession average levels.

Click here to expand the chart above

Throughout 2019, CDI values exhibited a declining trend in light of yield curve inversion and Fed cuts to the target federal funds rate during the back half of 2019. This trend accelerated in March 2020 when rates were effectively cut to zero. CDI values have shown some recovery in the past two quarters (average of 60 basis points for the first half of 2021 as compared to 50 basis points in the second half of 2020). Despite the recent uptick, CDI values remain below the post-recession average of 1.33% in the period presented in the chart and meaningfully lower than long-term historical levels which averaged closer to 2.5-3.0% in the early 2000s.

The average CDI value declined 11 basis points from June 2020 to June 2021, while the five year FHLB advance increased 25 basis points over the same period. Although the five year FHLB advance rate has increased year-over-year, rates on FHLB advances with terms of less than two years have declined an average of 11 basis points since this time last year.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, banks have been burdened with an excess of deposits. It was initially expected that the increase in deposits would be transient in nature as the economy re-opened, PPP funds were spent or invested, and consumer confidence improved. However, the glut of deposits has endured, and deposits at US commercial banks were at a record level of $17.3 trillion at the end of July despite earning historically low deposit rates. Weak loan demand has aggravated the issue for banks, and margin pressure remains a very real concern for financial institutions.

In past cycles, when interest rates declined, the change in the CDI/core deposit ratio was mostly caused by lower CDI values (the numerator in the ratio). In the pandemic, though, CDI values declined (due to lower rates) while core deposits increased (due to the governmental response to the pandemic among other factors). With market participants unwilling to pay a premium for potentially transient deposits, the CDI/core deposit ratio was squeezed by both lower CDI values (the numerator) and higher core deposits (the denominator). Time will tell how stable deposits will be after the deposit influx experienced in 2020 and the first half of 2021, which will affect CDI values going forward.

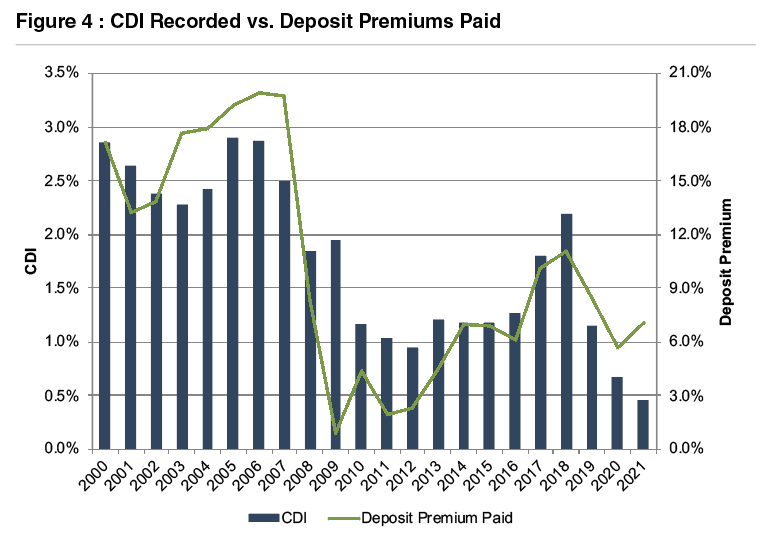

Trends In Deposit Premiums Relative To CDI Asset Values

Core deposit intangible assets are related to, but not identical to, deposit premiums paid in acquisitions. While CDI assets are an intangible asset recorded in acquisitions to capture the value of the customer relationships the deposits represent, deposit premiums paid are a function of the purchase price of an acquisition. Deposit premiums in whole bank acquisitions are computed based on the excess of the purchase price over the target’s tangible book value, as a percentage of the core deposit base.

While deposit premiums often capture the value to the acquirer of assuming the established funding source of the core deposit base (that is, the value of the deposit franchise), the purchase price also reflects factors unrelated to the deposit base, such as the quality of the acquired loan portfolio, unique synergy opportunities anticipated by the acquirer, etc.

Additional factors may influence the purchase price to an extent that the calculated deposit premium doesn’t necessarily bear a strong relationship to the value of the core deposit base to the acquirer. This influence is often less relevant in branch transactions where the deposit base is the primary driver of the transaction and the relationship between the purchase price and the deposit base is more direct. Figure 4 presents deposit premiums paid in whole bank acquisitions as compared to premiums paid in branch transactions.

As shown in Figure 4, deposit premiums paid in whole bank acquisitions have shown more volatility than CDI values. Deposit premiums in the rangeof 6% to 10% remain well below the pre-Great Recession levels when premiums for whole bank acquisitions averaged closer to 20%.

Deposit premiums paid in branch transactions have generally been less volatile than tangible book value premiums paid in whole bank acquisitions. Branch transaction deposit premiums averaged in the 4.5% to 7.5% range during 2019 and 3.0% to 7.5% during 2020, up from the 2.0% to 4.0% range observed in the financial crisis. Only eight branch transactions were completed in the first half of 2021, but the range of their implied premiums is in line with 2019 and 2020 levels.

Some disconnect appears to exist between the prices paid in branch transactions and the CDI values recorded in bank M&A transactions. Beyond the relatively small sample size of branch transactions, one explanation might be the excess capital that continues to accumulate in the banking industry, resulting in strong bidding activity for the M&A opportunities that arise–even in situations where the potential buyers have ample deposits.

Accounting For CDI Assets

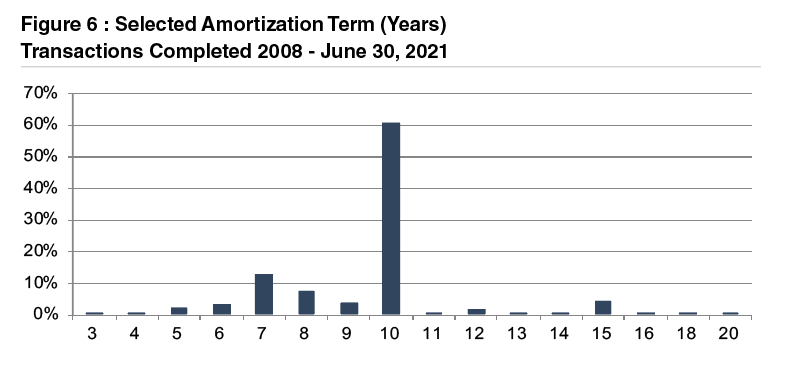

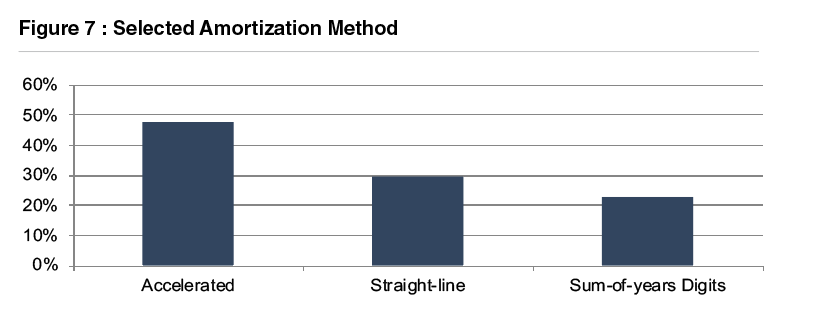

Based on the data for acquisitions for which core deposit intangible detail was reported, a majority of banks selected a ten-year amortization term for the CDI values booked. Less than 10% of transactions for which data was available selected amortization terms longer than ten years. Amortization methods were somewhat more varied, but an accelerated amortization method was selected in approximately half of these transactions.

For more information about Mercer Capital’s core deposit valuation services, please contact one of our professionals.

1 S&P Global Market Intelligence defines core deposits as, “Deposits, less time deposit accounts with balances over $100,000, foreign deposits and unclassified deposits”

Meet the Team – Scott A. Womack, ASA, MAFF

In each “Meet the Team” segment, we highlight a different professional on our Family Law team. The experience and expertise of our professionals allow us to bring a full suite of valuation and forensics services to our clients. We hope you enjoy getting to know us a bit better.

What attracted you to a career in litigation?

Scott Womack: I started doing divorce work about 13 years ago. Personally, I have found this work to be very rewarding. Divorce clients are very appreciative and I feel like I am making a difference as their Trusted Advisor throughout the process, but especially in mediation or during the trial. Often the non-business or out-spouse is not directly involved in the couple’s business and doesn’t know the value of the business or understand the process of valuation. These clients look to us to educate them and guide them through the process. Business owners or the in-spouse also see us as a value-add to the process, as they may have not gone through the business valuation process during their ownership of their company.

What type of cases give rise to your involvement in litigation matters?

Scott Womack: More often than not, I am involved in family law/divorce cases. The cases generally involve high wealth individuals and those that own businesses or business interests. In addition to the valuation and forensic work, I also participate in mediation to assist the client in an attempted settlement. If mediation is not successful, I generally submit a formal report to the Court and do testimony work at trial. Other litigation projects include breach of contract or shareholder disputes.

What drew you to financial forensics?

Scott Womack: A forensic credential allowed me to better analyze financial statements in divorce. Credentials help to frame your expertise and demonstrate your general ability to do your work. In a lot of divorce cases, especially if you are valuing a business, there can be forensic work. One example would be discretionary or personal expenses being paid through the business, which can have an impact on the value of the business as well as implications in the divorce such as possible dissipation or income available for support.

How has the valuation industry evolved since you started?

Scott Womack: Early in my career, the industry was comprised mostly of valuation generalists. In the early 2000s, financial statement reporting and valuations took on a whole new life of their own with purchase price allocations and stock based compensation. At this point, the valuation profession kind of exploded to become more specialized. We have people that now specialize in a specific service, be it divorce, financial statement reporting, or a particular industry. That is really what I have seen change. The movement from generalization to specialization. Especially for growth in your career, specialization is a great avenue for advancement by being able to be an expert in a field.

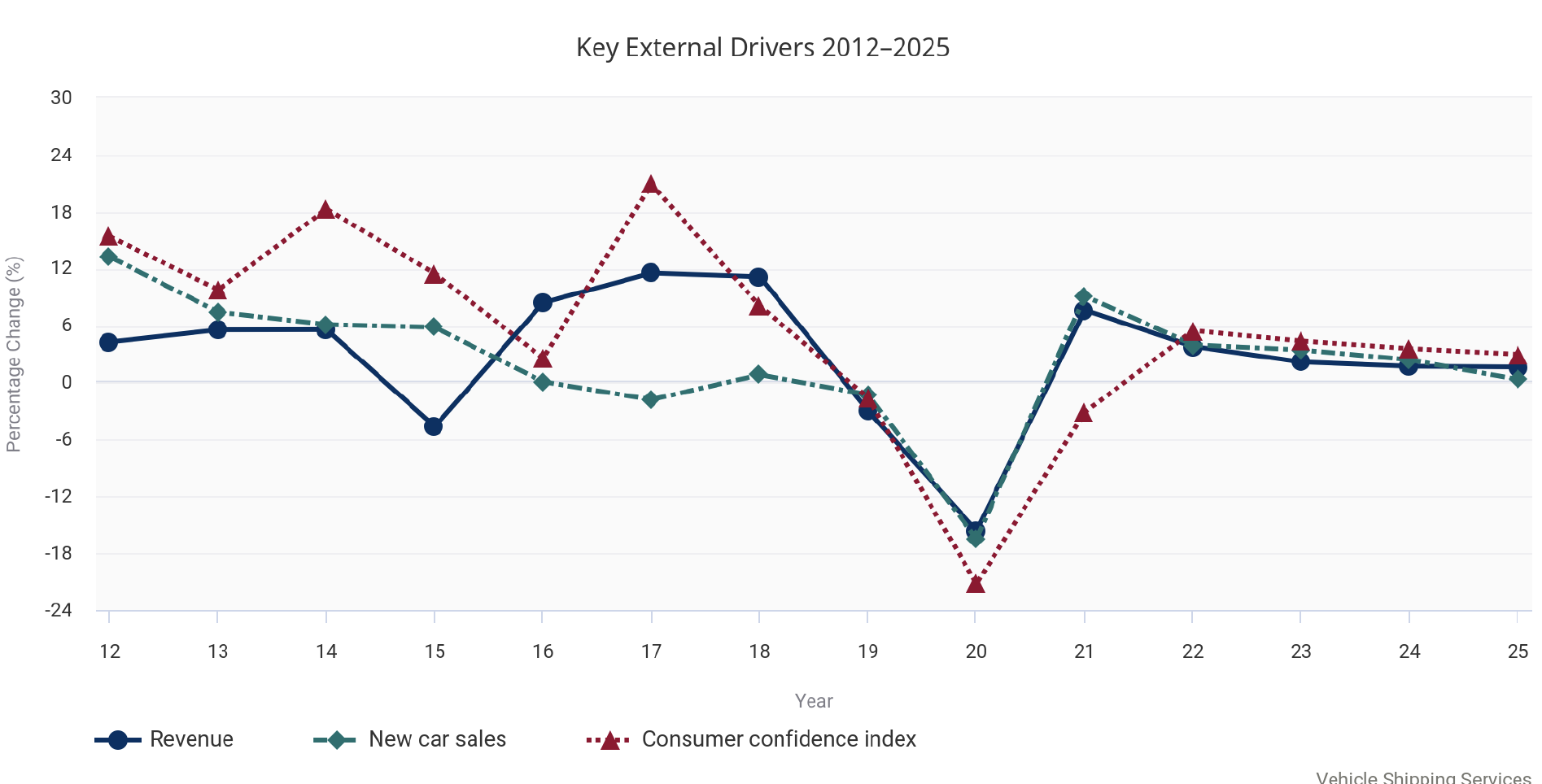

What influenced your concentration in the Auto Dealership Industry?

Scott Womack: I had a partner at my old firm who had several auto clients and I often got to work on those engagements. Some of these cases were related to divorce so I was able to see the litigation side as well. The Auto Dealership industry has some unique characteristics in its financial statements and operations. After being exposed to these differences I saw an opportunity to make an impact in this industry. I would be able to specialize in this area in order to provide the best valuation services possible.

What are a few unique characteristics of the Auto Dealership Industry?

Scott Womack: The financial statements are pretty unique in the Auto Dealership industry. Dealers have to submit monthly financials to manufacturers, and each manufacturer statement looks a little different, almost like trying to solve a puzzle. Due to the specialization and profit centers of the various departments, these statements have a lot of detail. They are very informative with not only the major categories like assets, liabilities, and revenues, but you can determine the size the service department or how many used vehicles they sold, what they’re selling them for, or how much inventory they have on the lot.

Not only do auto dealerships have to submit monthly statements, but some also report a thirteenth month statement. The thirteenth month takes the twelfth month with added year-end tax adjustments, normalization adjustments, etc. Furthermore, there is unique terminology in this industry. An example would be, “Blue-Sky”, which is the goodwill value of the dealership. It can encompass a number of factors and the Blue Sky value is often very meaningful to a dealer requesting a valuation.

There are also nuances in ownership and management that are important to know, as well as different valuation techniques and methodologies that are preferred. Someone specialized in this industry is better equipped to know what a client is looking for. I have found that my experience valuing auto dealerships has given me an advantage in knowing what to look for and what questions to ask.

What is one thing about your job that gets you excited to work every day?

Scott Womack: I have always enjoyed that the valuation and consulting business is project-based. On a project basis, you are able to work with different owners and different industries all across the board. One of my favorite parts of a project is conducting the management interviews and site visits. While the financial statements paint a picture and supply the quantitative results of operations, the management interviews provide much of the qualitative factors and allow you to gain an understanding of the company, the industry and the risk factors that they face. I enjoy meeting different business owners and learning about their successful companies and history.

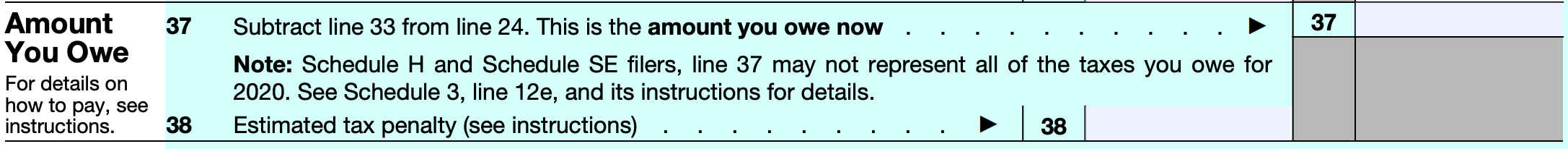

Understanding Transaction Advisory Fees

Real Expertise Is an Investment, and the Benefits in Return Should Well Exceed the Costs

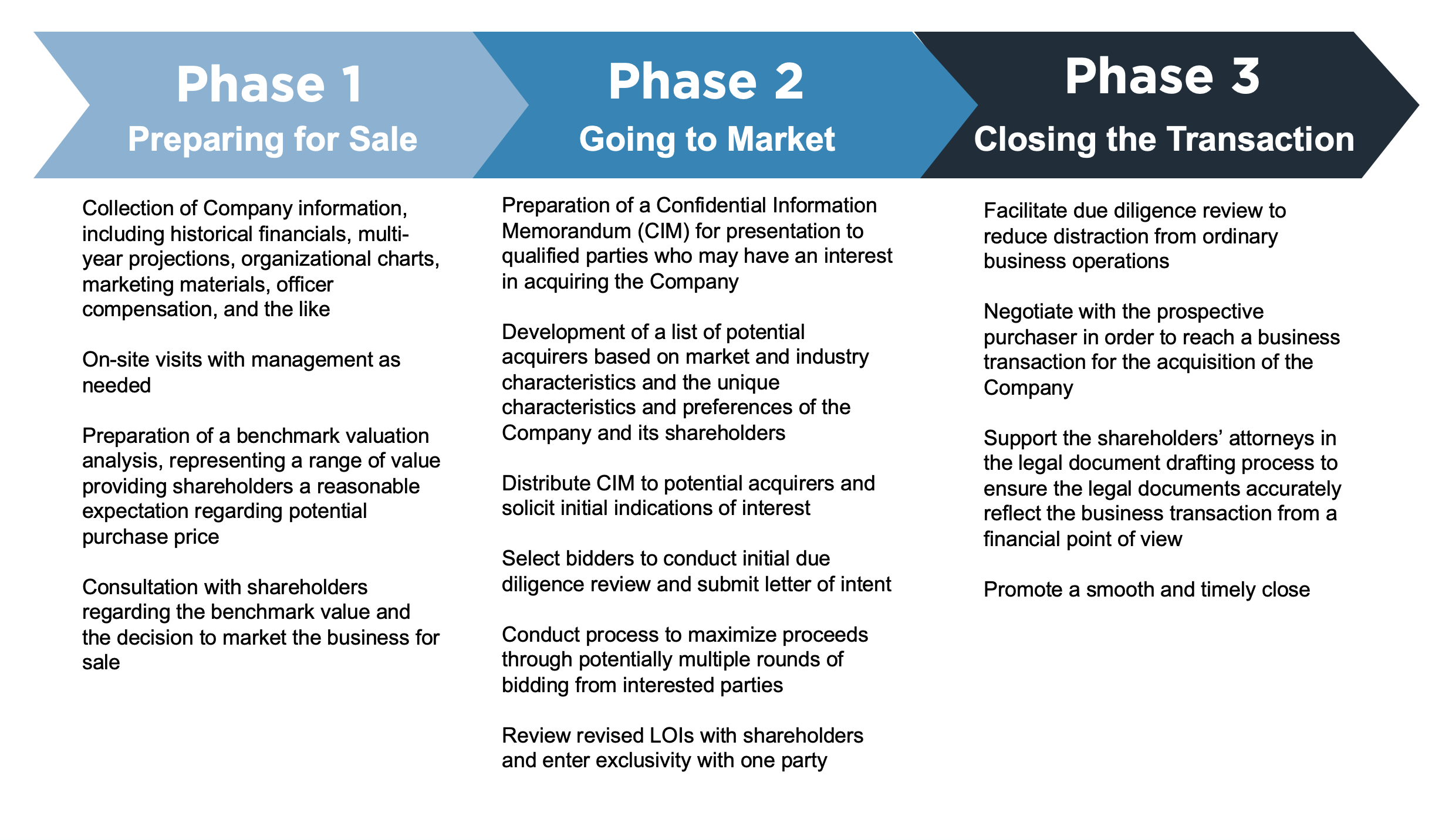

In the previous article, we highlighted the various benefits of hiring a financial advisor when investigating the potential sale of a business.

In a transaction with an outside party, the buyer will almost always be far more experienced in “deal-making” relative to the seller, who often will be undertaking the process for the first (and likely only) time. With such an imbalance, it is important for sellers to level the playing field by securing competent legal, tax and financial expertise.

A qualified sell-side advisor will help ensure an efficient process while also pushing to optimize the terms and proceeds of the transaction for the sellers.

As with anything in this world, favorable transaction processes and outcomes require an investment. Fee structures for transaction advisory services can vary widely based on the type and/or size of the business, the specific transaction situation, and the varying roles and responsibilities of the advisor in the transaction process.

Even with this variance, most fee structures fall within a common general framework and include two primary components: 1) Project Fees and 2) Success Fees.

Project Fees

Project fees are paid to advisors throughout an engagement for the various activities performed on the project. Such activities include the initial valuation assessment, development of the Confidential Information Memorandum, development of the potential buyer list, and other activities. These fees generally include an upfront “retainer” fee paid at the beginning of the engagement.

Retainer fees serve to ensure that a seller is serious about considering the sale of their business. For lower middle market transactions, the upfront retainer fee is typically in the $10,000 to $20,000 range.

Often times, a fixed monthly project fee will be charged throughout the term of the engagement. These fees are meant to cover some, but not all, of an advisor’s costs associated with the project.

For lower middle market transactions, monthly fees are typically $5,000 to $10,000. In certain situations, the engagement will include hourly fees paid throughout the engagement for the hourly time billed by the advisor. Such hourly fees are billed in place of a fixed monthly project fee.

Hourly fees are typically appropriate when the project is more advisory-oriented versus being focused on turn-key transaction execution. Hourly fees serve to emphasize the objective needs of the client by counter-balancing the incentive for an advisor to “push a deal through” that may not be in the best long-term interests of the client.

An hourly fee structure typically front loads the fees paid throughout the transaction process and is paired with a reduced success fee structure at closing which brings total fees back in line with market norms.

Mercer Capital has had favorable outcomes with numerous clients when fee structures are well-tailored to the facts and circumstances of the seller and the seller’s options in the marketplace.

Success Fee

A success fee is paid to a transaction advisor upon the successful closing of a transaction. Typically, success fees are paid as part of the disbursement of funds on the day of closing. As with project fees, success fees can be structured in a number of different ways.

A simple approach is to apply a flat percentage to the aggregate purchase price to calculate the success fee. The use of a flat percentage fee seems to have increased in recent years, and makes a fair bit of sense as it allows the client to clearly understand what the fees will look like on the back-end of a transaction.

Traditionally, the most used success fee structure employs a waterfall of rates and deal valuation referred to as the Lehman Formula. This formula calculates the success fee based on declining fee percentages applied to set increments (“tranches”) of the total transaction purchase price.

For lower middle market transactions, the simplest Lehman approach is a 5-4-3-2-1 structure: 5% on the first million dollars, 4% on the next million, and so on down to 1% on any amount above $4 million. The Lehman Formula, which can be applied using different percentages and varying tranche amounts, pays lower percentages in fee as the purchase price gets higher. Smaller deals may include a modified rate structure (for example 6-5-4-3-2) or may alter the tranche increments from $1 million to $2 million.

The Lehman Formula, in its varying forms, has been utilized to calculate transaction advisory fees for decades. While the formula may add some unnecessary complexities to the calculation (versus say a flat percentage), it has proven over time to provide reasonable fee levels from the perspective of both sell-side advisors and their clients.

A success fee can also be structured on a tiered basis, with a higher percentage being paid on transaction consideration above a certain benchmark. If base-level pricing expectations on a transaction are $15 million, the success fee might be set at 2.5% of the consideration up to $15 million and 5% of the transaction consideration above this level. If the business were sold for $18 million, the fee would be 2.5% of $15 million plus 5% of $3 million. The blended fee in this case would total $525,000, a little under 3% of the total consideration.

Escalating success fees are often favored by clients because they provide an incentive for advisors to push for maximized deal pricing rather than settling for an easier deal at a lower price.

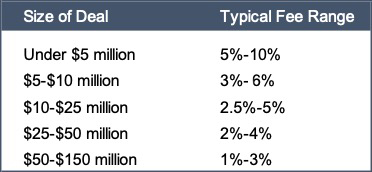

Typical Total Fees

Transaction advisory fees, on a percentage basis, tend to be higher for smaller transactions and decline as the dollars of transaction consideration increases. Various surveys of transaction advisors are available online that suggest typical fee ranges.

Consensus figures from these sources are outlined below. Based on our experience, these “typical” ranges (or at least the upper end of each range) appear to be somewhat inflated relative to what most business owners should expect in an actual transaction advisory engagement.

Mercer Capital’s View on Fees

At Mercer Capital, we tailor fees in every transaction engagement to fit both the transaction situation at hand and our client’s objectives and alternatives.

In situations where a client has an identified buyer, we understand that our role will likely be focused on valuation and negotiation. Many sellers are unaware that price is only one aspect of the deal, and terms are another. Altering the terms of a definitive agreement can move the needle by 5%-10% and can potentially accelerate end-game liquidity by 6 to 12 months.

Accordingly, we design each fee structure to recognize what we are bringing to the process, typically utilizing some combination of hourly billings and a tiered success fee structure on the portions of the deal where our services are making a difference in the total outcome.

If we are assisting a client through a full auction process, it may be appropriate to utilize a more traditional Lehman Formula or a flat percentage calculation. A primary focus of our initial conversations with a potential client is to understand the situation in detail so that we can develop a fee structure that ensures that the client receives a favorable return from their investment in our services.

Mercer Capital provides transaction advisory services to a broad range of public and private companies and financial institutions. We have worked on hundreds of consummated and potential transactions since Mercer Capital was founded in 1982.

Mercer Capital leverages its historical valuation and investment banking experience to help clients navigate critical transactions, providing timely, accurate, and reliable results. We have significant experience advising shareholders, boards of directors, management, and other fiduciaries of middle-market public and private companies in a wide range of industries.

Rather than pushing solely for the execution of any transaction, Mercer Capital positions itself as an advisor, encouraging the right decision to be made by its clients. We recommend to clients to accept the right deal or no deal at all.

Our dedicated and responsive team is available to manage your transaction process. To discuss your situation in confidence, give us a call.

The SEC Adopts New Rule 2a-5 for Valuation of Fund Portfolio Investments

Summary

In December 2020, the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) adopted a new rule 2a-5 to update the regulatory framework around valuations of investments held by a registered investment company or business development company (“fund”). Boards of directors of funds are obligated to determine fair value of investments without readily available market quotations in good faith under the Investment Company Act of 1940 (“Act”).

Rule 2a-5 specifies requirements to fulfill these obligations. Concurrently, the SEC also adopted rule 31a-4, which provides recordkeeping requirements related to fair value determinations. Rule 2a-5 was effective as of March 2021, and funds are required to be compliant upon the conclusion of an 18-month transition period following the effective date (voluntary early compliance allowed).

Valuation Framework

Prior to adopting rule 2a-5, the SEC last addressed valuation practices under the Act more than 50 years ago. Over the intervening period, the variety of securities and other instruments held by investment funds has proliferated. The volume and type of data used in valuations have also increased. Funds increasingly use third-party services to provide pricing information, especially for relatively illiquid or otherwise complex assets. In addition, accounting standards and regulatory requirements have advanced including developments related to ASC 820, Fair Value Measurement.

Against this backdrop, rule 2a-5 establishes a framework consisting of four primary functions required to determine fair value in good faith. A fund board may choose to determine fair value by executing the functions. Rule 2a-5 also allows a fund board to designate these functions to a “valuation designee.” The required functions are:

- Periodically assess and manage valuation risks, including conflicts of interest. The rule does not prescribe a required minimum frequency for re-assessing valuation risks, instead stating that different frequencies may be appropriate for different funds or risks. Re-assessment of valuation risks should generally consider changes in fund investments, significant changes in investment strategies or policies, market events, and other relevant factors.

- Establish and apply fair value methodologies. Satisfying this function will require selecting and applying appropriate valuation methodologies, periodically reviewing the appropriateness and accuracy of the methodologies (and making any necessary changes or adjustments), and monitoring for circumstances that may necessitate the use of fair value. A fund board or the valuation designee is required to specify key inputs and assumptions used in the valuation of particular asset classes or portfolio holdings. Appropriate valuation methodologies for investments may vary, even within the same asset class. However, these methodologies are expected to be applied consistently to minimize the risks of selecting methodologies to achieve a specific outcome. Further, the rule states that appropriate methodologies must be consistent with the principles outlined in ASC 820.

- Test fair value methodologies for appropriateness and accuracy. This function is intended to ensure the selected valuation methodologies are appropriate and adjustments are made as necessary. The fund board or the valuation designee should identify the testing methods and the minimum frequency with which such methods will be used. However, the rule does not prescribe any particular testing method or specific minimum testing frequency. Examples of testing methods include calibration and back-testing against valuations obtained from observed transactions.