My seventeen year old daughter is getting pretty deep into her college search; she’s narrowed it down to a handful of schools that are between 1,000 miles from home and 4,000 miles from home, if that tells you anything. A few weeks ago she told an admissions officer from a really fine school in California that she is “interested in politics,” but that she doesn’t want to be a politician; instead she’s interested in “economics as they relate to public policy, especially tax policy.” I learned this over dinner one night.

I know I should have teared up with pride, but instead I lost my appetite.

Having my creative, funny, yet also quantitatively astute daughter sell her soul not just to the dismal science of economics but in particular Washington’s never ending quest to pervert the dismal science...feels a little like an act of betrayal - like her telling me that her dream car is a Saturn. At least it hasn’t come to that.

For Once, Taxes Are Not Boring

Because we like our readers, the RIA team at Mercer assiduously avoids talking about tax policy in this blog. The Trump tax bill, however, can’t go without mention. We won’t mince words – this tax bill is a blockbuster for the investment management industry. Whatever your politics, you can’t ignore the magnitude of the change that is afoot.

Among the issues presented by the tax bill is that advisor fees are no longer a line-item deduction for clients, an interesting shot at investors by this administration that doesn’t line up very well with the tax treatment of other professional services. While this is peculiar, David Canter recently published an interview with industry leaders Brent Brodeski and Michael Nathanson that cautions against making too much of this.

We’re staying focused on the implications of the tax bill for investment management firm valuations, and there’s much to consider.

The Tax Bill Has Driven Up AUM (for Most)

Investment management revenue is a function of AUM, and the impact of the tax bill on valuations across a spectrum of asset classes is significant. While the impact of this on anyone who derives fee income from managing equities (fixed income shops are a different story) is clear, we don’t think it’s sufficient to just take the increase in market valuations at face; it’s more useful to unpack the issue and consider why.

One of our colleagues here at Mercer, Travis Harms, did some research on the impact of the tax bill on valuation multiples to consider not just the what but also the why. Notably, Travis looked at the impact on pre-tax multiples, such as EBITDA, to interrogate whether or not a dollar of pre-tax cash flow is indeed worth more if it is less burdened with tax liabilities. Travis is interested in the change in multiples because he works heavily in the portfolio valuation space. We saw broad implications to his modeling exercise for the investment management community.

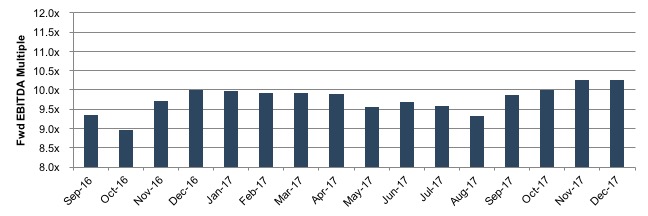

Travis pulled monthly forward EBITDA multiples for the S&P 1000 (ex financials). The S&P 1000 is a combined mid and small cap index, consisting of company #501 through #1500. As shown in the following chart, the median multiple for such firms was approximately 9.0x to 9.5x during the fall of 2016, when a Clinton administration, and tax status quo, seemed inevitable. By late 2017, the median multiple had expanded by almost a full turn, to about 10.3x.

Forward EBITDA multiples for sample equity index (S&P 1000 ex financials) shows movement in multiples that appear to correlate with changes in the outlook for corporate tax reductions.

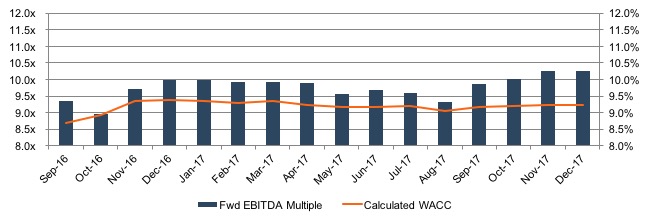

Valuation multiples are, of course, a function of three factors: 1) cash flow, 2) risk, and 3) growth. To determine whether or not the change in multiples is indeed attributable to a change in tax rates, Travis investigated whether or not there had been an effective change in the cost of capital (risk) or an expectation of increased growth in earnings. Travis’s analysis inferred an aggregate cost of capital (supply side weighted average cost of capital, or WACC) for his equity basket in September of 2016 as an anchor point, and then looked at the change in the cost of capital over the same period that resulted from a change in interest rates (holding the assumed equity risk premium constant).

Forward EBITDA multiples for sample equity index (S&P 1000 ex financials) shows movement in multiples that appear to correlate with changes in the outlook for corporate tax reductions.

Valuation multiples are, of course, a function of three factors: 1) cash flow, 2) risk, and 3) growth. To determine whether or not the change in multiples is indeed attributable to a change in tax rates, Travis investigated whether or not there had been an effective change in the cost of capital (risk) or an expectation of increased growth in earnings. Travis’s analysis inferred an aggregate cost of capital (supply side weighted average cost of capital, or WACC) for his equity basket in September of 2016 as an anchor point, and then looked at the change in the cost of capital over the same period that resulted from a change in interest rates (holding the assumed equity risk premium constant).

The risk-free rate (the interest rate on long dated treasuries) gapped up from close to 2.0% in September of 2016 to something on the order of 2.8% in December of that year, pushing the implied supply side cost of capital up to about 9.2%.

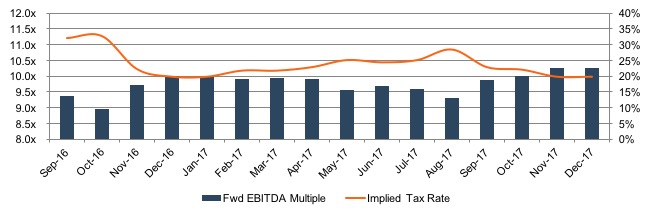

Doing some fancy footwork, Travis ran a DCF model on his equity basket, letting the tax rate float. His DCF model suggests that the market priced in effective tax rates of approximately 20% by the end of 2017. Significantly, the early expectations for rate reduction seem to have waned a bit over the summer months as the Trump administration experienced a series of legislative failures. Also significant is that the model assumes there are no changes in the expected growth outlook for the companies in the sample basket, consistent with statements from the Federal Reserve suggesting no material uptick in GDP growth consequent from the tax bill. Travis didn’t modify expected growth because there is no robust way to review earnings estimates for a broad array of companies on a month by month basis. Of note, Aswath Damodaran, a finance professor at NYU, thinks the tax bill may in fact increase the sustainable growth rate for U.S. companies.

The risk-free rate (the interest rate on long dated treasuries) gapped up from close to 2.0% in September of 2016 to something on the order of 2.8% in December of that year, pushing the implied supply side cost of capital up to about 9.2%.

Doing some fancy footwork, Travis ran a DCF model on his equity basket, letting the tax rate float. His DCF model suggests that the market priced in effective tax rates of approximately 20% by the end of 2017. Significantly, the early expectations for rate reduction seem to have waned a bit over the summer months as the Trump administration experienced a series of legislative failures. Also significant is that the model assumes there are no changes in the expected growth outlook for the companies in the sample basket, consistent with statements from the Federal Reserve suggesting no material uptick in GDP growth consequent from the tax bill. Travis didn’t modify expected growth because there is no robust way to review earnings estimates for a broad array of companies on a month by month basis. Of note, Aswath Damodaran, a finance professor at NYU, thinks the tax bill may in fact increase the sustainable growth rate for U.S. companies.

Using a DCF model framework to evaluate the impact of a change in tax expectations on valuation multiples, we can let the cost of capital float with interest rates and hold growth expectations constant, such that the change in valuation multiples can be attributed to the change in tax rates.

The implication of Travis’s analysis is that the market repriced as a consequence of lower tax rates, and not because of changes in the cost of capital (which, with higher interest rates, would have caused multiples to fall), nor expectations of higher earnings growth (of which there is little evidence).

Put another way, the tax bill appears to have, indeed, inflated equity valuation multiples by reducing the tax burden on corporate profits. On one level, this is obvious, but the implications of this are interesting if it also suggests that current equity valuations are more sustainable than some believe. Perhaps valuation multiples gapped higher, as they should have, and will remain higher than they would otherwise be, so long as corporate tax rates persist at these levels. That would certainly be good news for the asset management community.

Using a DCF model framework to evaluate the impact of a change in tax expectations on valuation multiples, we can let the cost of capital float with interest rates and hold growth expectations constant, such that the change in valuation multiples can be attributed to the change in tax rates.

The implication of Travis’s analysis is that the market repriced as a consequence of lower tax rates, and not because of changes in the cost of capital (which, with higher interest rates, would have caused multiples to fall), nor expectations of higher earnings growth (of which there is little evidence).

Put another way, the tax bill appears to have, indeed, inflated equity valuation multiples by reducing the tax burden on corporate profits. On one level, this is obvious, but the implications of this are interesting if it also suggests that current equity valuations are more sustainable than some believe. Perhaps valuation multiples gapped higher, as they should have, and will remain higher than they would otherwise be, so long as corporate tax rates persist at these levels. That would certainly be good news for the asset management community.

The Tax Bill Has Improved RIA Economics (for Many)

Taking this one step further, the tax bill would seem to have improved returns for many subsectors of the investment management industry. If public market valuations gapped up 10% or so, would we expect to see nearly a 10% increase in assets under management across the equity space in the industry? More AUM means more revenue and more profitability? In short, yes, as we can show in the example below.

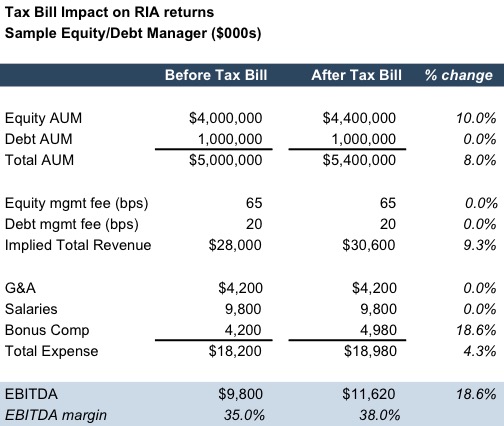

This table is fairly self-explanatory. Assuming an RIA with $5 billion under management, of which 80% is managed equities and 20% is fixed income, a 10% increase in equity valuations would have a corresponding 8% increase in overall AUM, ceteris paribus.

If the same investment management firm realized fees of 65 basis points on equities and 20 basis points on fixed income, the leverage on the higher AUM attributable to equities would increase revenue a bit more than total AUM, or 9.3%. One potential problem with this aspect of the model is the assumption that clients with higher AUM balances won’t pass through breakpoints that will lower overall realized fees. For purposes of this example, however, we have assumed that the fee schedule isn’t progressive with the increase in AUM.

When we consider the leverage on operating expenses, however, things really get interesting. Higher AUM balances can lead to a correspondingly higher expense base if the increase comes from more accounts or assets that are more expensive to manage. In this instance, however, AUM is simply inflated because of market activity. We might not assume G&A costs would rise at all, nor would, necessarily, salaries. Incentive compensation, however, would probably increase. Assuming bonus compensation to be 30% of pre-bonus EBITDA, we see an almost 20% increase in incentive compensation resulting from higher assets under management. Even with higher bonuses, however, total expenses only increase about 4%. The consequence of this is an increase in earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization of almost 20%, and a cash flow margin increase of three percentage points.

If you’re an asset manager, your reality may (will) be different than our example. If interest rates continue to rise, our sample RIA might experience some diminution in income from managing fixed income portfolios. Clients may rebalance to maintain the same allocation between stocks and bonds. Clients are, on the whole, more fee sensitive than they once were, and may want some betterment of their fee schedule as a consequence of this moment of good fortune. And your staff will probably notice that there is more cash flow available for compensation. The market may bid up the cost of talent, or at least salaries and bonuses will increase more than we show here in an effort to “keep a good thing going.” In any event, if your AUM increases nearly 10% and margins don’t widen, it would be worth looking through your numbers some to assess why. The opportunity for a significant increase in profitability at many RIAs appears to be on offer.

This table is fairly self-explanatory. Assuming an RIA with $5 billion under management, of which 80% is managed equities and 20% is fixed income, a 10% increase in equity valuations would have a corresponding 8% increase in overall AUM, ceteris paribus.

If the same investment management firm realized fees of 65 basis points on equities and 20 basis points on fixed income, the leverage on the higher AUM attributable to equities would increase revenue a bit more than total AUM, or 9.3%. One potential problem with this aspect of the model is the assumption that clients with higher AUM balances won’t pass through breakpoints that will lower overall realized fees. For purposes of this example, however, we have assumed that the fee schedule isn’t progressive with the increase in AUM.

When we consider the leverage on operating expenses, however, things really get interesting. Higher AUM balances can lead to a correspondingly higher expense base if the increase comes from more accounts or assets that are more expensive to manage. In this instance, however, AUM is simply inflated because of market activity. We might not assume G&A costs would rise at all, nor would, necessarily, salaries. Incentive compensation, however, would probably increase. Assuming bonus compensation to be 30% of pre-bonus EBITDA, we see an almost 20% increase in incentive compensation resulting from higher assets under management. Even with higher bonuses, however, total expenses only increase about 4%. The consequence of this is an increase in earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization of almost 20%, and a cash flow margin increase of three percentage points.

If you’re an asset manager, your reality may (will) be different than our example. If interest rates continue to rise, our sample RIA might experience some diminution in income from managing fixed income portfolios. Clients may rebalance to maintain the same allocation between stocks and bonds. Clients are, on the whole, more fee sensitive than they once were, and may want some betterment of their fee schedule as a consequence of this moment of good fortune. And your staff will probably notice that there is more cash flow available for compensation. The market may bid up the cost of talent, or at least salaries and bonuses will increase more than we show here in an effort to “keep a good thing going.” In any event, if your AUM increases nearly 10% and margins don’t widen, it would be worth looking through your numbers some to assess why. The opportunity for a significant increase in profitability at many RIAs appears to be on offer.

The Tax Bill Has Improved RIA valuations (for Some)

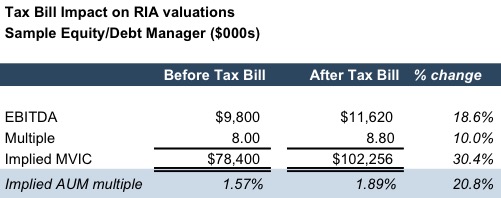

Taking this one step further, RIAs may not only benefit from a repricing of market multiples of their clients’ assets, but also of the value of their own returns. In our example firm, EBITDA increases 18.6% as a direct consequence of the tax bill. Valuations of RIAs would be expected to increase similarly, if there were no change in the valuation multiples for the RIAs themselves.

If, however, appropriate multiples for RIAs gap-up 10% like Travis Harms observed happened in the public equity market, then the combination of that plus improved profitability produces a 30% increase in enterprise values for RIAs, and a corresponding 20% expansion in the implied AUM multiple. The reason for the increase in RIA multiples is the same as the increase in the market basket of equities Travis studied: a dollar of pre-tax cash flow is worth more when the tax burden on that dollar is less (assuming no change in the cost of capital or earnings growth).

If, however, appropriate multiples for RIAs gap-up 10% like Travis Harms observed happened in the public equity market, then the combination of that plus improved profitability produces a 30% increase in enterprise values for RIAs, and a corresponding 20% expansion in the implied AUM multiple. The reason for the increase in RIA multiples is the same as the increase in the market basket of equities Travis studied: a dollar of pre-tax cash flow is worth more when the tax burden on that dollar is less (assuming no change in the cost of capital or earnings growth).

Your Results May (Will) Differ

Whatever you do, don’t run out of your office and tell your partners that I’ve just proven your firm is worth 30% more than it was two months ago. There are many variables that affect firm valuation – some discussed in this post, some I’ve left out, and some I probably haven’t thought of yet. One issue in comparing movement in the public market multiples and private RIAs is that public companies are C-corporations whereas many, if not most, private RIAs are some kind of tax pass-through entity like an S corporation or an LLC. I’ll be back next week to talk about how the tax bill treats tax pass through enterprises, and it’s not nearly as generous as conferred upon C corps.

In any event, the tax bill is bullish for the RIA community. There may not be a Saturn in my driveway, but a friend of mine who, like me, was born under the astrological sign of Capricorn says that Saturn is in our house this year (cosmologically, a favorable thing). I don’t know what the “Saturn” effect is for the markets, but for now it appears that the stars are aligned for the RIA community, an augur of good things to come.

If you have questions as you wrestle with the valuation implications of the new tax bill on your RIA, give us a call to discuss your situation in confidence and/or register for our upcoming webinar addressing the matter.