In 1973 Ford Motor Company committed brand espionage by replacing its reigning muscle car, the Mustang, with a slow and cramped economy box as an alleged successor: the Mustang II. Whereas earlier versions of the Mustang were fitted with a reasonably powerful V-6 and much more powerful V-8 motors, the best the “II” could boast was a smallish V-6 from the Capri. With all of 105 horsepower, the V-6 enabled Mustang II could meander to 60 miles per hour in about 13 seconds (given level pavement and favorable winds).

We covered much of what we think the new tax bill will mean to RIA valuations in last week’s blogpost – and it’s mostly good news. The “rest of the story” involves the bill’s impact on shareholder returns for RIAs structured as tax pass-thru entities (S corporations, LLCs, Partnerships), for which the news is not so buoyant.

As with the Mustang II, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act took a good thing and made it not so good. The S corporation was a fairly brilliant innovation from the 1950s, allowing certain small businesses to benefit from the limited liability of a being a corporation yet file their taxes as partnerships. S corporations (and LLCs) “pass-through” the tax liability on profits to their shareholders rather than pay one layer of tax at the corporate level on company profits and another at the shareholder level on dividends.

Why Many RIAs are Structured as Tax Pass-Through Entities

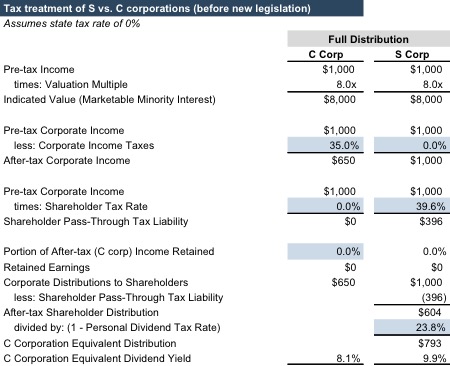

Before the Trump Tax Bill, it often made sense to structure investment management firms as tax pass through entities – usually S corporations or LLCs. As shown in the table below, given taxable income of, say, $1 million, a C corporation would only have $650 thousand to distribute after paying federal corporate taxes at a rate of 35%. Even though the same $1 million of taxable income would be taxed at a higher personal rate for S corporation shareholders, the after-tax distribution of $604 thousand would have a higher economic value when you consider S corp shareholders skip the dividend tax (paid at 23.8%) that would accrue to the C corporation shareholder. After grossing up the after-tax dividend to the S corp shareholder at the C corporation dividend tax rate, the S corporation shareholder earns a C corporation equivalent dividend of nearly $800 thousand. Assuming the RIA in this example is valued at 8x pre-tax income, the S corp shareholder experiences a distribution yield that is 180 basis points higher than if his or her RIA were structured as a C (all else equal).

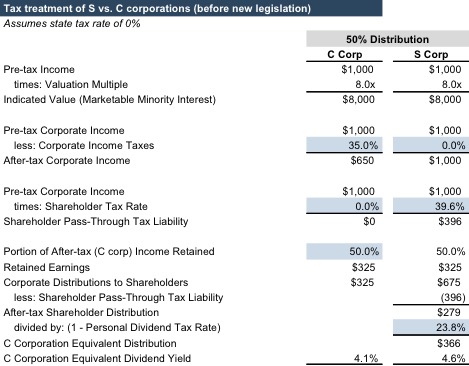

The example above assumes a fully distributing RIA, since many if not most RIA clients we’ve encountered over the years dividend out something close to 100% of their net income. But the S corporation yield advantage also exists if, say, an RIA only distributes half of the C corp equivalent after-tax income (or, conversely, retains half of net income).

The example above assumes a fully distributing RIA, since many if not most RIA clients we’ve encountered over the years dividend out something close to 100% of their net income. But the S corporation yield advantage also exists if, say, an RIA only distributes half of the C corp equivalent after-tax income (or, conversely, retains half of net income).

Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Mutes S Corp Advantage

The new tax legislation has a big impact on C corporation taxes, a more modest impact on personal income taxes, and no effect on capital gains taxes. As a consequence, the economic advantage of organizing as an S corporation or LLC has been whittled away to almost nothing in some cases, and is arguably disadvantageous in other cases.

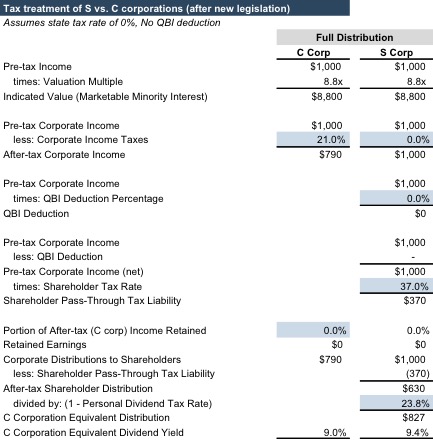

The table below depicts the comparative consequences of the new tax bill on RIAs organized as C corporations and S corporations. For C corporations, the fourteen percentage point drop in corporate tax rates improves the after tax income available for distribution considerably. In our example, a fully distributing C corporation with $1 million in pre-tax income would have $790 thousand in after-tax income to distribute to shareholders – a substantial improvement over the $650 thousand available under the old tax rates.

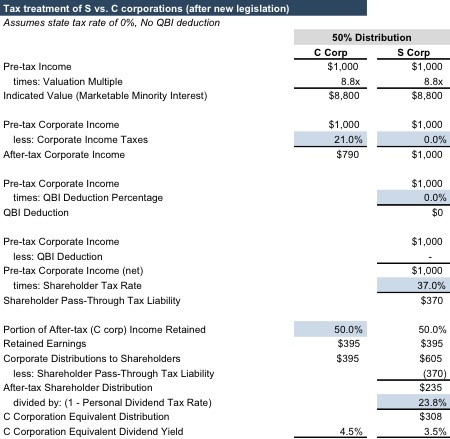

For S corporations and LLCs, however, the taxes on pass-through income are still substantial, as the after-tax distribution only improves from $604 thousand to $630 thousand (yes, it still improves). If you gross this up for taxes that would be owed on the C corporation dividend, you arrive at a C corporation equivalent dividend of $827 thousand, or not much more than the $790 thousand dividend available for the C corporation. The dividend yield advantage narrows from 180 basis points before the tax legislation to 40 basis points after the tax legislation (assuming some improvement in the valuation multiple – as discussed in last week’s blogpost). The comparison is even worse for investment management firms structured as tax pass-through entities but don’t distribute all of their net income. Going back to the example of the firms that distribute half of their after tax earnings (on a C corp equivalent basis), the dividend yield for the C corporation improves under the new legislation from 4.1% to 4.5%, even with a higher valuation. The S corp yield drops, however, assuming the same earnings retention as the C, from 4.6% to 3.5%, notably lower than the dollar amount and percentage distribution yield for the C corporation.

For S corporations and LLCs, however, the taxes on pass-through income are still substantial, as the after-tax distribution only improves from $604 thousand to $630 thousand (yes, it still improves). If you gross this up for taxes that would be owed on the C corporation dividend, you arrive at a C corporation equivalent dividend of $827 thousand, or not much more than the $790 thousand dividend available for the C corporation. The dividend yield advantage narrows from 180 basis points before the tax legislation to 40 basis points after the tax legislation (assuming some improvement in the valuation multiple – as discussed in last week’s blogpost). The comparison is even worse for investment management firms structured as tax pass-through entities but don’t distribute all of their net income. Going back to the example of the firms that distribute half of their after tax earnings (on a C corp equivalent basis), the dividend yield for the C corporation improves under the new legislation from 4.1% to 4.5%, even with a higher valuation. The S corp yield drops, however, assuming the same earnings retention as the C, from 4.6% to 3.5%, notably lower than the dollar amount and percentage distribution yield for the C corporation.

(Probably) No QBI Deduction for You

Knowing that they were trimming back the S corporation advantage, the tax bill introduced a new concept, the Qualified Business Income deduction, that allows certain S shareholders to deduct 20% of their pass-through income and, therefore, maintain more of the S corporation differential in tax rates. However, in a very interesting and possibly more revealing move, the QBI deduction is NOT available for investment management firms.

Congress decided to exclude certain “specified service trade or business” income from qualifying for the deduction. One excluded business is investment management: “The term ‘specified trade or business’ means any trade or business – (B) which involves the performance of services that consist of investing and investment management, trading, or dealing in securities (as defined in section 475(c)(2)), partnership interests, or commodities (as defined in section 475(e)(2)).” Of note, Congress had never, to our knowledge, previously singled out investment management for specific treatment as a “specified service trade or business.” Like the limitation on the deductibility of financial planning fees mentioned last week, it appears this administration is taking aim at the RIA community (while inexplicably allowing QBI deductions for architects and engineers).

Despite the exclusion, the QBI deduction remains available to RIA shareholders for whom total income is less than $315 thousand; the deduction phases out until it is completely unavailable at incomes greater than $415 thousand. As a result, many RIA shareholders will not get the benefit of the Qualified Business Income deduction.

Final Thoughts and Parting Shots

So, like the Mustang II, the tax bill is new but not necessarily improved for owners of RIAs structured as S corporations or LLCs (excluding the impact of generally higher AUM balances discussed in last week’s post). The Trump administration didn’t aim its product at the investment management community any more than Ford was looking after driving enthusiasts in the early 1970s. It could be worse, though. In the mid-1980s Ford tried to ruin the Mustang’s reputation again with a version that was also underpowered and, this time, front wheel drive. Mustang fans balked, and Ford released the car as an entirely separate product: the Probe, a name that may suggest how some RIA partners feel about the new tax law after they file their 2018 return.