Vulcan Materials’ Acquisition of U.S. Concrete

Is the Price Right?

As participants in and observers of mergers and acquisitions, the 2021 acquisition of U.S. Concrete, Inc. (“U.S. Concrete”) by Vulcan Materials Company (“Vulcan Materials”) (NYSE: VMC) is a terrific opportunity to study the valuation nuances of the construction and building materials industry. In this article, we look at the fairness opinions delivered by Evercore and BNP Paribas rendered to the U.S. Concrete board regarding the transaction and provide some observations on the methodologies utilized by these two investment banks.

First, a little background on the two parties to the transaction before we delve into the analysis. At the time of the acquisition, U.S. Concrete was a publicly traded leading supplier of aggregates and concrete for infrastructure, residential, and commercial projects across the country, holding leading positions in high-growth metropolitan markets. Vulcan Materials, a member of the S&P 500 index, is the largest producer of construction aggregates, such as crushed stone, sand, and gravel in the U.S. and a major producer of aggregates-based construction materials such as asphalt and ready-mix concrete.

U.S. Concrete agreed to be acquired by Vulcan Materials at a price of $74.00 per share, or $1.3 billion, on June 7, 2021. The $74.00 per share offer price represented an approximate 30% premium to U.S. Concrete’s closing stock price of $57.14 on June 4, 2021, the last trading day before the deal was announced. The implied enterprise value of the deal was tallied at $2.1 billion. Deal multiples included 27.5x analysts’ consensus EPS for the next 12 months and 10.3x NTM EBITDA.

This deal was no surprise to industry observers. U.S. Concrete had engaged Evercore for strategic advisement during the onslaught of COVID-19, as the company’s stock price had dropped from $41.25 per share on January 2, 2020 to an intraday low of $6.75 on March 18, 2020. Evercore and U.S. Concrete considered numerous strategic actions, including executing a noncore disposition, growing the aggregates segment, and pursuing additional capital, but ultimately, U.S. Concrete decided the best path forward was to merge with Vulcan Materials.

The Evercore and BNP Paribas Fairness Opinions

The proxy statement dated July 13, 2021 enumerated the reasons the U.S. Concrete board approved the merger agreement, including the fairness opinions that opined the consideration to be received by U.S. Concrete shareholders was fair from a financial point of view. (A link to the proxy statement can be found here).

A fairness opinion provides an analysis of the financial aspects of a proposed transaction from the point of view of one or more parties to the transaction, usually expressing an opinion about the consideration though sometimes the transaction itself. Ideally, the opinion is provided by an independent advisor that does not stand to receive a success fee, especially when the transaction is a close call or involves real or perceived conflicts. In the case of the Vulcan Materials-U.S. Concrete transaction, both U.S. Concrete advisors stood to receive much larger contingent fees if the transaction was consummated compared to the fixed fee fairness opinions. Evercore received a fee of $3 million for the fairness opinion and was to be paid a success fee of $19.75 million. BNP Paribas’ opinion and success fees were $2.0 million and $6.4 million, respectively.

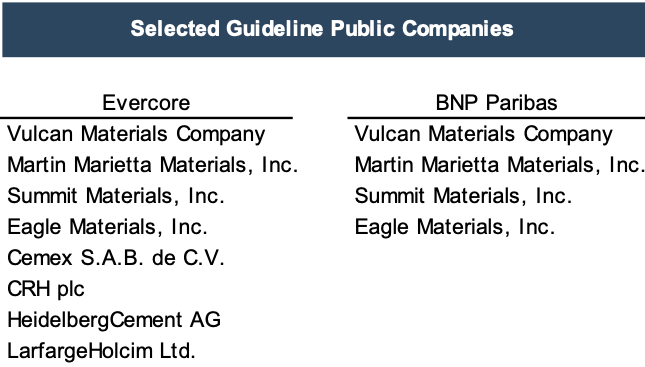

Guideline Public Company (“GPC”) Analysis

Evercore and BNP Paribas reviewed and compared specific financial and operating data relating to U.S. Concrete with selected GPCs deemed comparable to U.S. Concrete. The GPC’s used by each advisor were as follows. We note that Evercore selected four additional GPCs in addition to the four selected by BNP Paribas. We are not privy to Evercore’s reasoning for selecting the four additional GPCs.

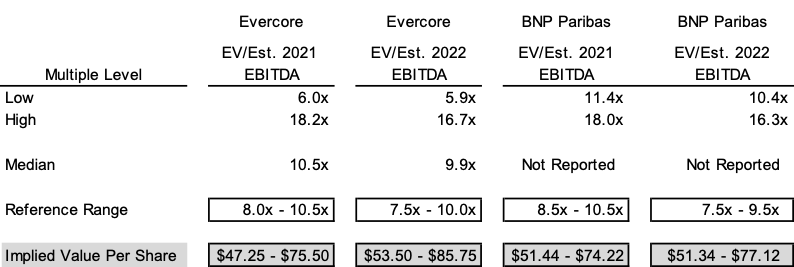

The following table compares the selected GPC’s high, low, and median EV/estimated EBITDA multiples, the reference ranges of multiples selected by Evercore and BNP Paribas, which were based on quantitative and qualitative factors alike, and an implied equity value per share, determined through the relevant ranges of multiples.

Both banks used publicly available market estimates and financial data, including S&P Cap IQ, to estimate EBITDA; however, BNP Paribas also took consensus analyst research estimates into account when determining the figures. When determining the relevant range, both BNP Paribas and Evercore used qualitative factors such as size, market exposure, growth prospects, and profitability levels alongside quantitative factors.

A quick glance at the table above indicates that Evercore’s reference range for both EV/estimated 2021 EBITDA and EV/estimated 2022 EBITDA generally falls above the lowest observed multiple on the low-end and approximates the median observed multiple on the high-end. While BNP Paribas’ respective reference ranges are nearly identical to Evercore’s reference ranges, BNP Paribas’ reference ranges fall below the lowest multiples observed for its selected GPCs. Presumably, Evercore’s selection of four additional GPCs has influenced Evercore’s reference ranges.

Guideline Transaction (M&A) Analysis

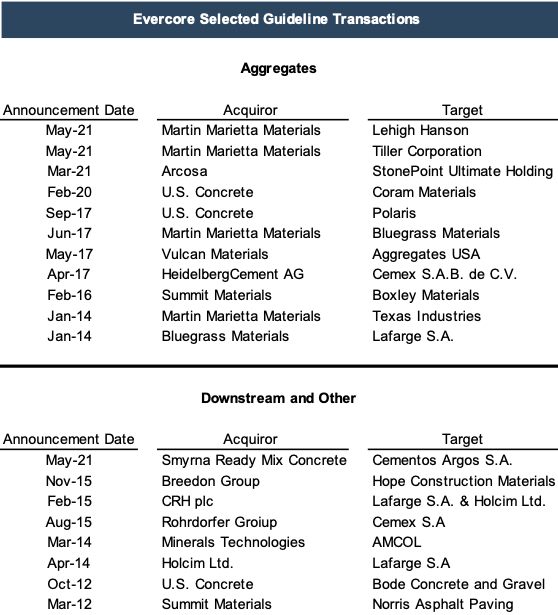

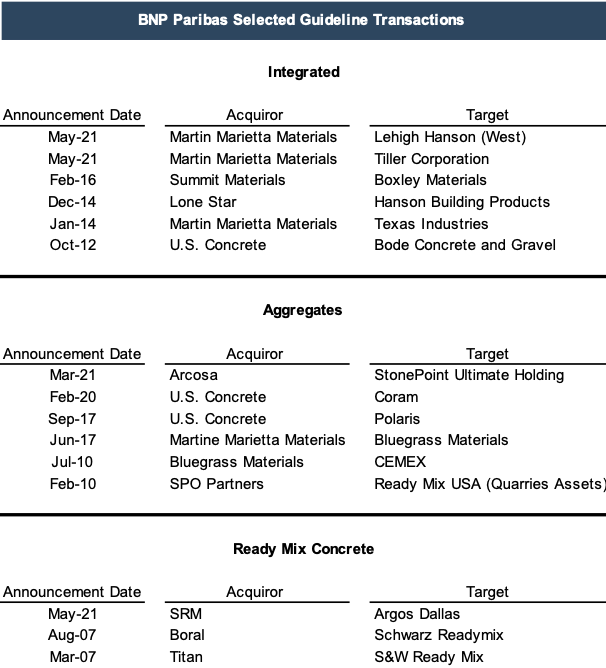

Evercore and BNP Paribas both explored past transactions of controlling interests in companies operating in the same industries as U.S. Concrete and Vulcan Materials to make assumptions about the equity value based on the implied multiples of each transaction. The transactions examined by each company are listed below. Evercore segregated its selected guideline transactions into two groups, Aggregates and Downstream and Other while BNP Paribas segregated its selected guideline transactions into three groups, Integrated, Aggregates, and Ready-Mix Concrete.

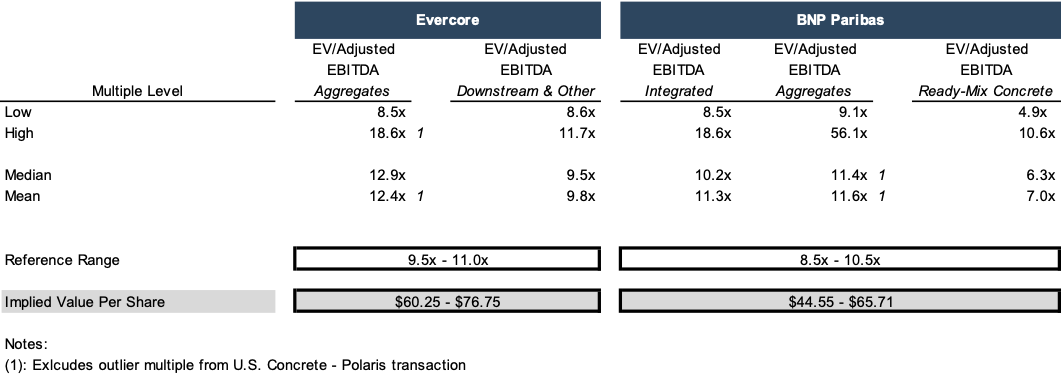

The analyses of both companies’ approaches to transactions are shown below.

Click here to expand the image above

These multiples lead each bank to a very different conclusion in terms of guideline transactions. With a reference range of 9.5x-11.0x, Evercore’s analytics indicate that equity value should range between $60.25 and $76.75 per share. BNP Paribas settled on an 8.5x-10.5x reference range, implying an equity value between $44.55 and $65.71. We note the following observations from the guideline transaction approaches taken by Evercore and BNP Paribas:

- A one turn higher multiple on the low-end (from 8.5x to 9.5x) results in a 35.2% higher value by Evercore

- A half-turn higher multiple on the high-end (from 10.5x to 11.5x) results in a 16.8% higher value by Evercore

- BNP Paribas’ high-end equity value per share of $65.71 is only 9.1% higher than Evercore’s low-end equity value per share of $60.25.

Discounted Cash Flow Analysis

Both Evercore and BNP Paribas performed a discounted cash flow (“DCF”) analysis. The DCF is used universally across business valuation, and especially so in fairness opinions. The gist of the analysis reflects the discounting of unlevered cash flows over a discrete period and the projected debt-free value of the company at the end of the projection period to present values based upon the weighted average cost of capital. Net debt is then subtracted to derive the indicated equity value.

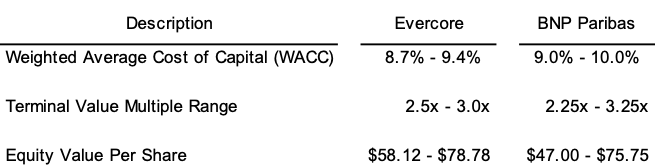

A quick glance at the table below reveals that Evercore’s low-end DCF analysis produced an equity value per share approximately 23.7% higher than BNP Paribas’ low-end DCF analysis, but Evercore’s high-end DCF analysis produced an equity value per share only approximately 4.0% higher than BNP Paribas high-end DCF analysis.

Historical Share Price Analysis

Both banks reviewed the 52-week trading history ending on June 4, 2021 ($20.77-$78.99 per share) for U.S. Concrete and compared this range to both the merger price of $74.00 per share and the closing price on June 4th at $57.14 per share. However, both banks noted that they only used this data for informational purposes and that it was not taken into consideration for the valuation process of U.S. Concrete.

Research Analyst’s Price Targets

Just like the historical share price analysis, the research analyst’s price targets were not considered material for either bank’s valuation. Nevertheless, the range of price targets that both Evercore and BNP Paribas observed spanned from $39.00 to $80.00 with Evercore stating a median target at $65.00.

BNP Paribas’ and Evercore’s Conclusions

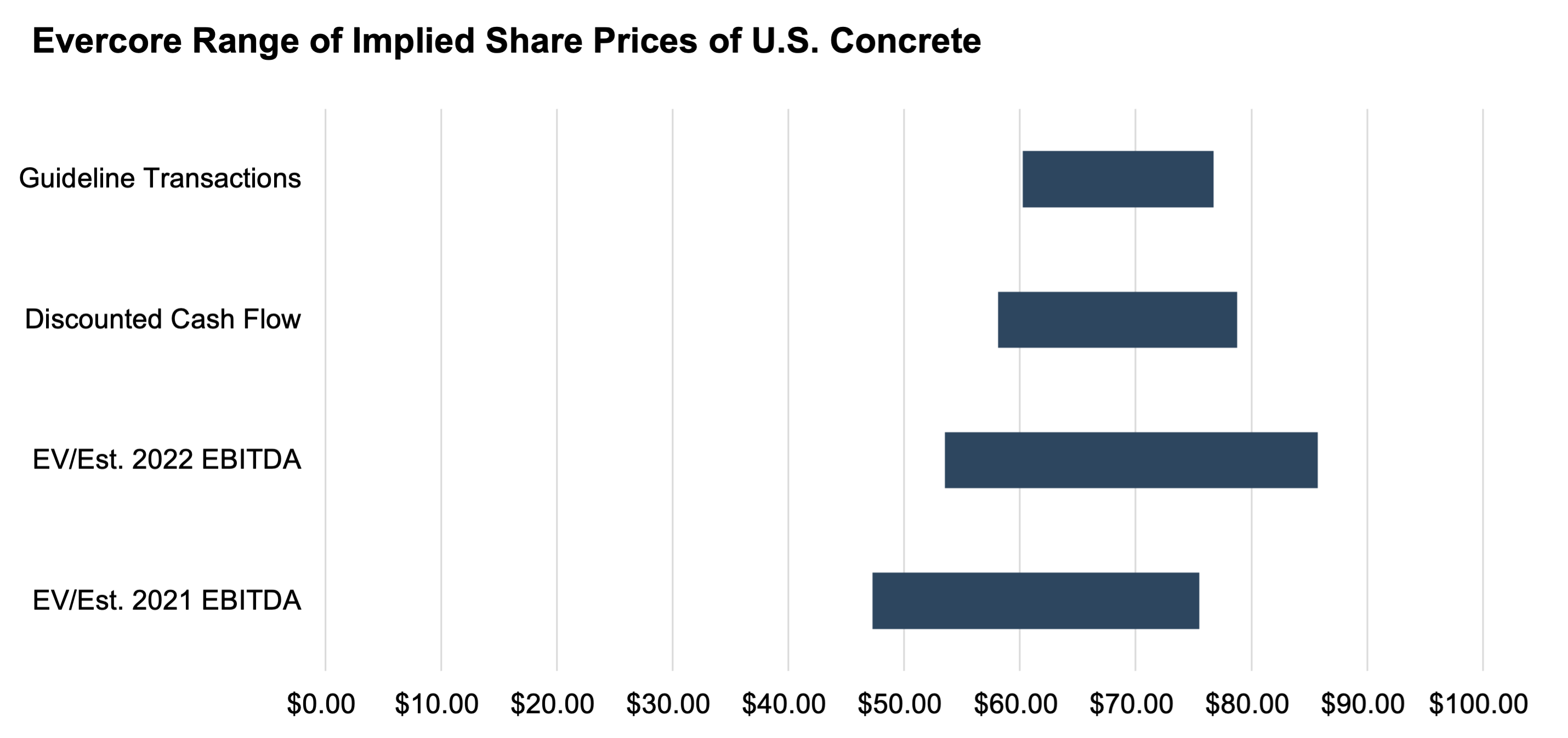

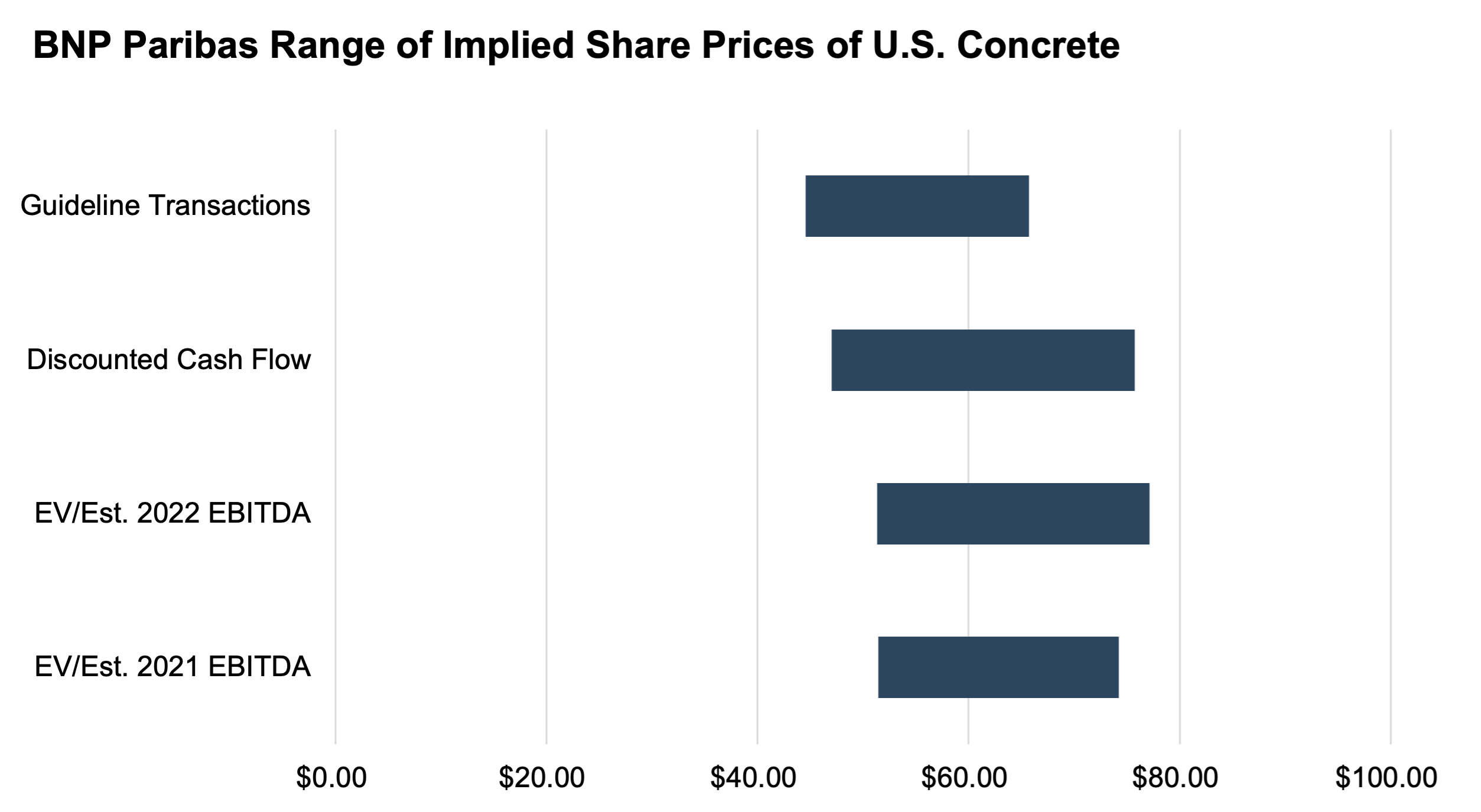

Both banks opined that, from a financial point of view, the consideration to be received by the stockholders of U.S. Concrete in the proposed transaction was fair to such stockholders. As can be seen in the graph below, the $74.00 share price fits into most ranges towards the top end of each range in both banks’ valuations. The deal was officially completed and closed on August 26, 2021.

*All charts and figures in the article are sourced from U.S. Concrete, Inc.’s Schedule 14A Proxy Statement

Connelly v. United States – Considerations in Divorce

Our founder, Chris Mercer, recently wrote a case review regarding the Supreme Court’s decision in the matter of Connelly v. United States. This case involved two brothers, Michael and Thomas Connelly, who were the sole shareholders of a small building supply corporation. They entered into an agreement to ensure that the company would stay in the family if either passed away. Under that agreement, the corporation would be required to redeem (i.e., purchase) the deceased brother’s shares. To fund the possible share redemption, the corporation obtained life insurance on each brother. After Michael died, a dispute arose over how to value his shares for calculating his estate tax. The central question is whether the corporation’s obligation to redeem Michael’s shares was a liability that decreased the value of those shares.

The primary takeaway from that decision is that life insurance received at the death of a shareholder is a corporate asset that adds to the value of the company for federal gift and estate tax purposes.

While the case itself directly addressed tax law, with regard to deferred compensation and taxation of assets, its implications extend beyond tax law alone. This ruling also has relevance in the realm of divorce valuations, where the accurate assessment of assets is crucial. In this article we highlight some specific areas where the Connelly case has relevance for business owner clients going through a divorce.

Tax Implications and Fair Division

In the context of Connelly v. United States, when calculating the federal estate tax, the value of a decedent’s shares in a closely held corporation must reflect the corporation’s fair market value. Life-insurance proceeds payable to a corporation are an asset that increase fair market value. The question in this case is whether the contractual obligation to redeem the decedent’s shares at fair market value offsets the value of life-insurance proceeds committed to funding that redemption.

The Supreme Court concluded no. Because the Court determined a fair-market-value redemption has no effect on any shareholder’s economic interest, and no hypothetical buyer purchasing the decedent’s shares would have treated the life-insurance obligation as a factor that reduced the value of those shares.

However, the decision is a reminder also for family law valuations to consider future tax liabilities when dividing marital assets pursuant to a divorce. The eventual tax obligations should be accounted for in the present value of the settlement. Otherwise, one spouse could potentially receive an asset that appears more valuable but carries a significant tax burden when eventually realized.

Deferred Assets and Equitable Distribution of Risk

The Connelly decision underscores the idea that risk should be considered in asset valuation. In divorce cases, this suggests family law matter should account for potential fluctuations in the value of deferred corporate assets, ensuring that both parties share equally in any future financial risks or rewards. Another element is timing.

Should stock options granted during the marriage but vesting after divorce be valued at the date of divorce assuming the full stock options or considering a coverture fraction on the stock options?

Designed to both reward performance and retain employees, these benefits can be difficult to value, particularly at a random moment for the purpose of marital dissolution. The Connelly decision provides a useful analogy by emphasizing that the timing of valuation has material consequences and can affect how equitable the division appears in hindsight.

The Need for a Financial Expert

Most family law cases that require the use of a financial expert share some combination of the following: a high-dollar marital estate, complex financial issues, business valuation(s) performed, and/or the need for forensic services. In the Connelly case, there were intricate financial issues regarding the life insurance corporate asset as well as the potential corporate liability to repurchase shares upon the death of a shareholder.

Conclusion

Determining the present value for deferred compensation assets like pensions or life-insurance plans can be legally and financially complex. When these types of situations occur in the context of a divorce, an experienced financial expert that can communicate their opinions and conclusions on these issues is a priceless asset for your team.

Buy-Sell Agreements: Valuation Handbook for Attorneys

Published by the American Bar Association, Buy-Sell Agreements: Valuation Handbook for Attorneys is a one-of-a-kind resource for attorneys representing business owners.

Well-prepared buy-sell agreements establish a valuation process to set the price at which a transaction will occur when trigger events happen. Many, if not most, buy-sell agreements in existence today have dated language pertaining to the description of their appraisal processes and the definitions of the price to be set by these processes.

The book, penned by Mercer Capital’s Z. Christopher Mercer, FASA, CFA, ASA, a business appraiser and veteran of many buy-sell agreement disputes, scrutinizes common issues in current agreements and suggests improvements.

The book also provides seven elements that should be clearly defined in every agreement, including:

- Standard of value (like fair market value)

-

Level of value (like financial control)

-

Going concern requirement

-

“As-of” date

-

Qualifications of appraisers

-

Appraisal standards to be followed

-

Consideration of life insurance proceeds

The importance of this last element has been heightened by the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Connelly, which affects buy-sell agreements involving life insurance, as discussed in the book’s appendix.

Importantly, the book provides example language for consideration by attorneys when drafting buy-sell agreements that contain language important to the valuation process.

Attorneys will find that Buy-Sell Agreements: Valuation Handbook for Attorneys will be an invaluable resource for reviewing existing agreements or drafting new ones.

** NOTE ** : Clicking the “Add to Cart” button takes you to the ABA’s website where you can order.

2024 Core Deposit Intangibles Update

Since Mercer Capital’s most recently published article on core deposit trends in September 2023, deal activity in the banking industry has continued to be rather anemic, but could be showing signs of recovery. Although deal activity has been slow, we have seen a marginal uptick in core deposit intangible values relative to this time last year.

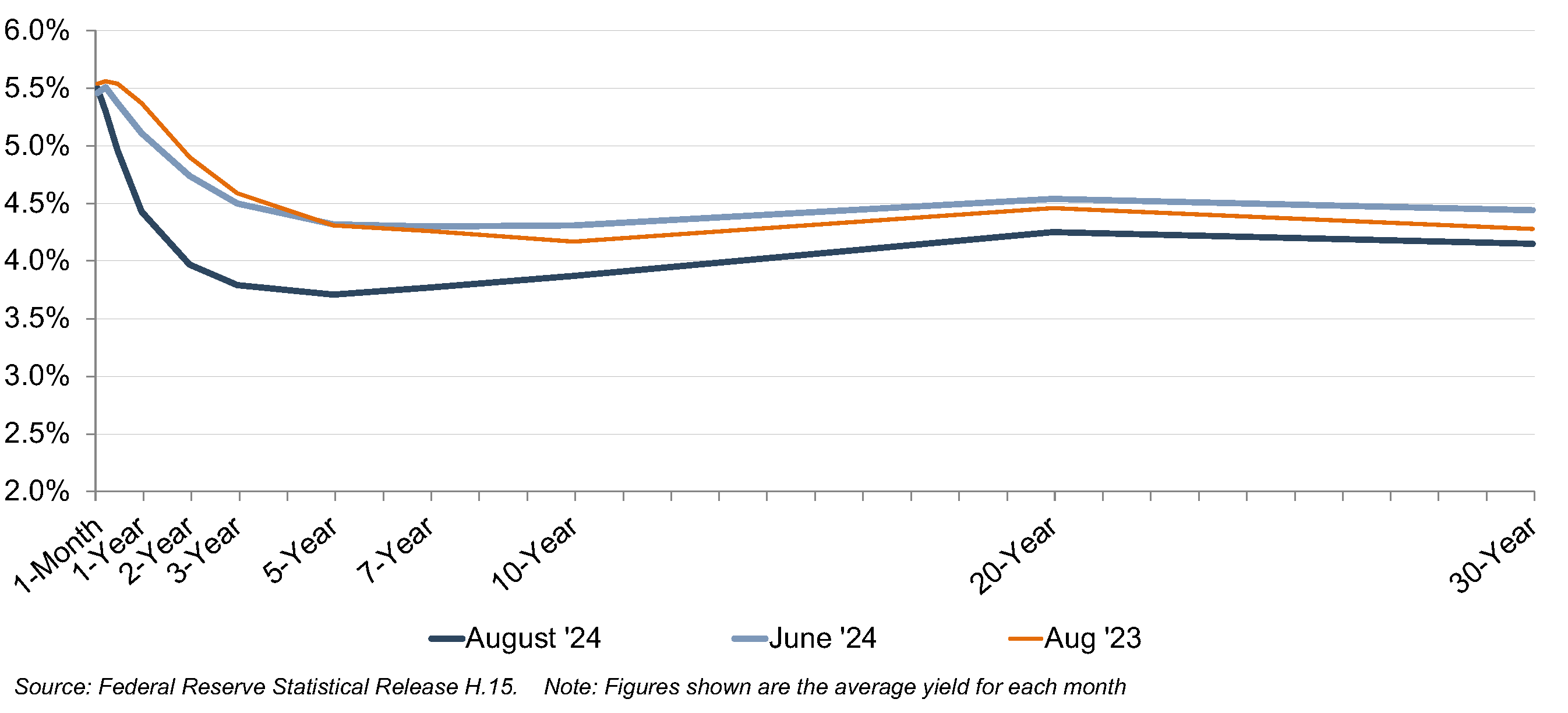

On July 26, 2023, the Federal Reserve increased the target federal funds rate by 25 basis points, capping off a collective increase of 525 basis points since March 2022. Although cuts to the fed funds target rate were anticipated several times over the past year, no changes materialized until the Federal Reserve’s September 2024 meeting. While many factors are pertinent to analyzing a deposit base, a significant driver of value is market interest rates. All else equal, lower market rates lead to lower core deposit values. As shown below, the yield curve for U.S. Treasuries has shifted downward relative to last year at this time, and the market expects further downward movement in short-term rates in the near term.

Figure 1: U.S. Treasury Yield Curve

Trends in CDI Values

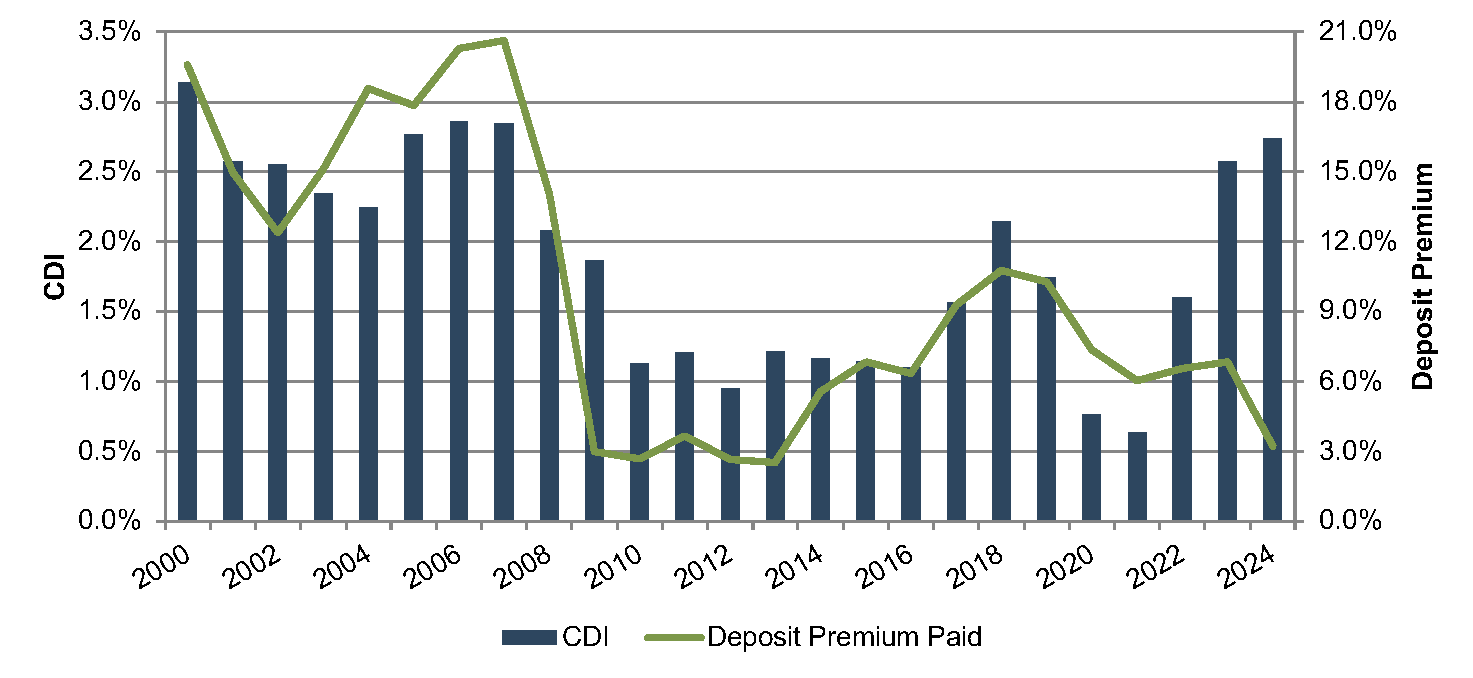

Using data compiled by S&P Capital IQ Pro, we analyzed trends in core deposit intangible (CDI) assets recorded in whole bank acquisitions completed from 2000 through mid-September 2024. CDI values represent the value of the depository customer relationships obtained in a bank acquisition. CDI values are driven by many factors, including the “stickiness” of a customer base, the types of deposit accounts assumed, the level of noninterest income generated, and the cost of the acquired deposit base compared to alternative sources of funding. For our analysis of industry trends in CDI values, we relied on S&P Capital IQ Pro’s definition of core deposits.1 In analyzing core deposit intangible assets for individual acquisitions, however, a more detailed analysis of the deposit base would consider the relative stability of various account types. In general, CDI assets derive most of their value from lower-cost demand deposit accounts, while often significantly less (if not zero) value is ascribed to more rate-sensitive time deposits and public funds. Non-retail funding sources such as listing service or brokered deposits are excluded from core deposits when determining the value of a CDI.

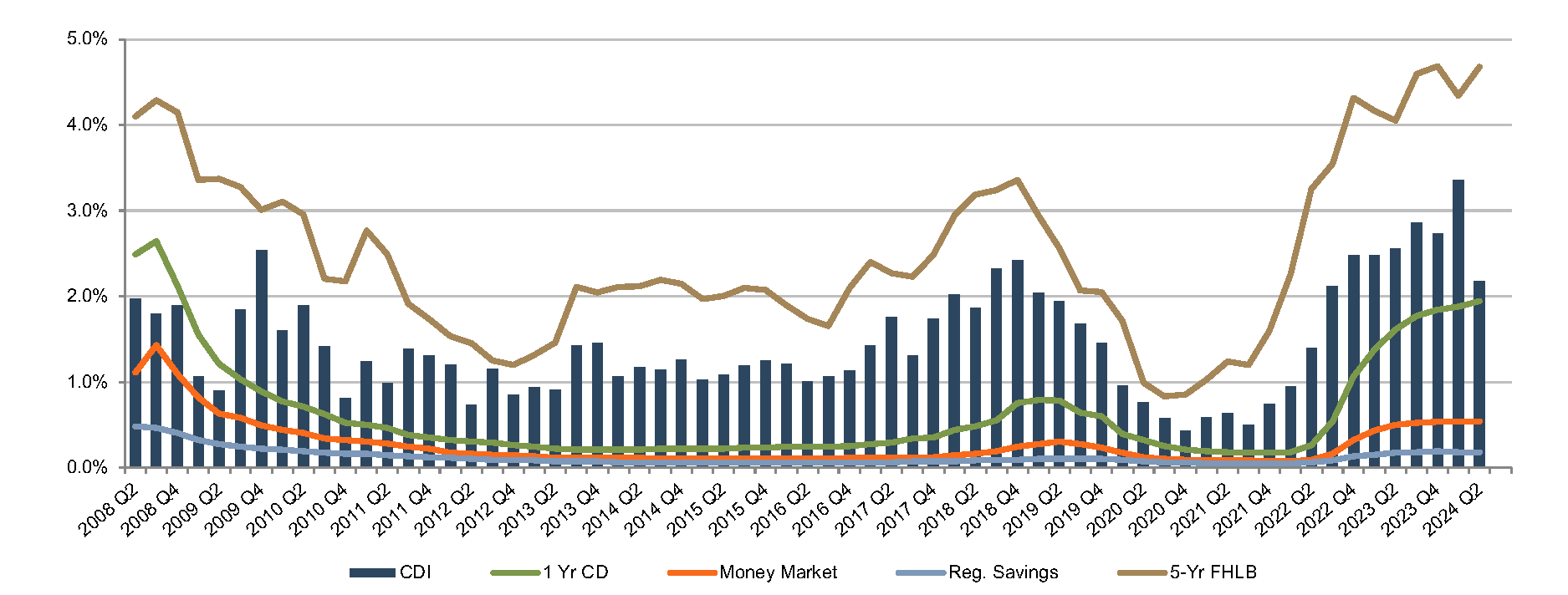

Figure 2, on the next page, summarizes the trend in CDI values since the start of the 2008 recession, compared with rates on 5-year FHLB advances. Over the post-recession period, CDI values have largely followed the general trend in interest rates—as alternative funding became more costly in 2017 and 2018, CDI values generally ticked up as well, relative to post-recession average levels. Throughout 2019, CDI values exhibited a declining trend in light of yield curve inversion and Fed cuts to the target federal funds rate during the back half of 2019. This trend accelerated in March 2020 when rates were effectively cut to zero.

Figure 2: CDI as % of Acquired Core Deposits

Source: S&P Capital IQ Pro

Click here to expand the image above

CDI values have increased meaningfully in the past few years (averaging 2.74% through mid-September 2024). This compares to 2.58% all of 2023, 1.61% all of 2022 and 0.63% for all of 2021. Recent values are above the post-recession average of 1.47%, and on par with longer-term historical levels which averaged closer to 2.5% to 3.0% in the early 2000s.

As shown in Figure 2, reported CDI values have followed the general trend of the increase in FHLB rates. However, the averages should be taken with a grain of salt. The chart is provided to illustrate the general directional trend in value as opposed to being predictive of specific indications of CDI value due the following factors:

- Last week’s Federal Reserve rate cuts are not reflected in the data above. While the impact on CDI values of one 50 basis point reduction in the fed funds target rate may not be highly material—given that the forward rate curve has anticipated falling short-term interest rates for some time—continued reductions in the fed funds target rate or downward shifts in the yield curve may result in a larger decline in CDI values.

- General market averages do not reflect the individual characteristics of a particular subject’s deposit base.

- Some of the values presented above reflect the estimated core deposit intangible value at deal announcement, rather than the final core deposit intangible value as determined post-closing.

Twenty-three deals were announced in July, August, and the first half of September, and ten of those deals provided either investor presentations or earnings calls containing CDI estimates. Excluding one outlier with a 1.06% estimated CDI value, these CDI estimates ranged from 2.7% to 4.1%. However, the CDI premiums cited in investor presentations can be somewhat difficult to compare, as acquirers may use different definitions of core deposits when calculating the CDI premiums reported to investors. For example, some acquirers may include CDs in the calculation, while other buyers may exclude CDs or include only certain types of CDs.

Generally, we expect CDI values to fall in concert with falling market interest rates. How fast they decline could depend several factors:

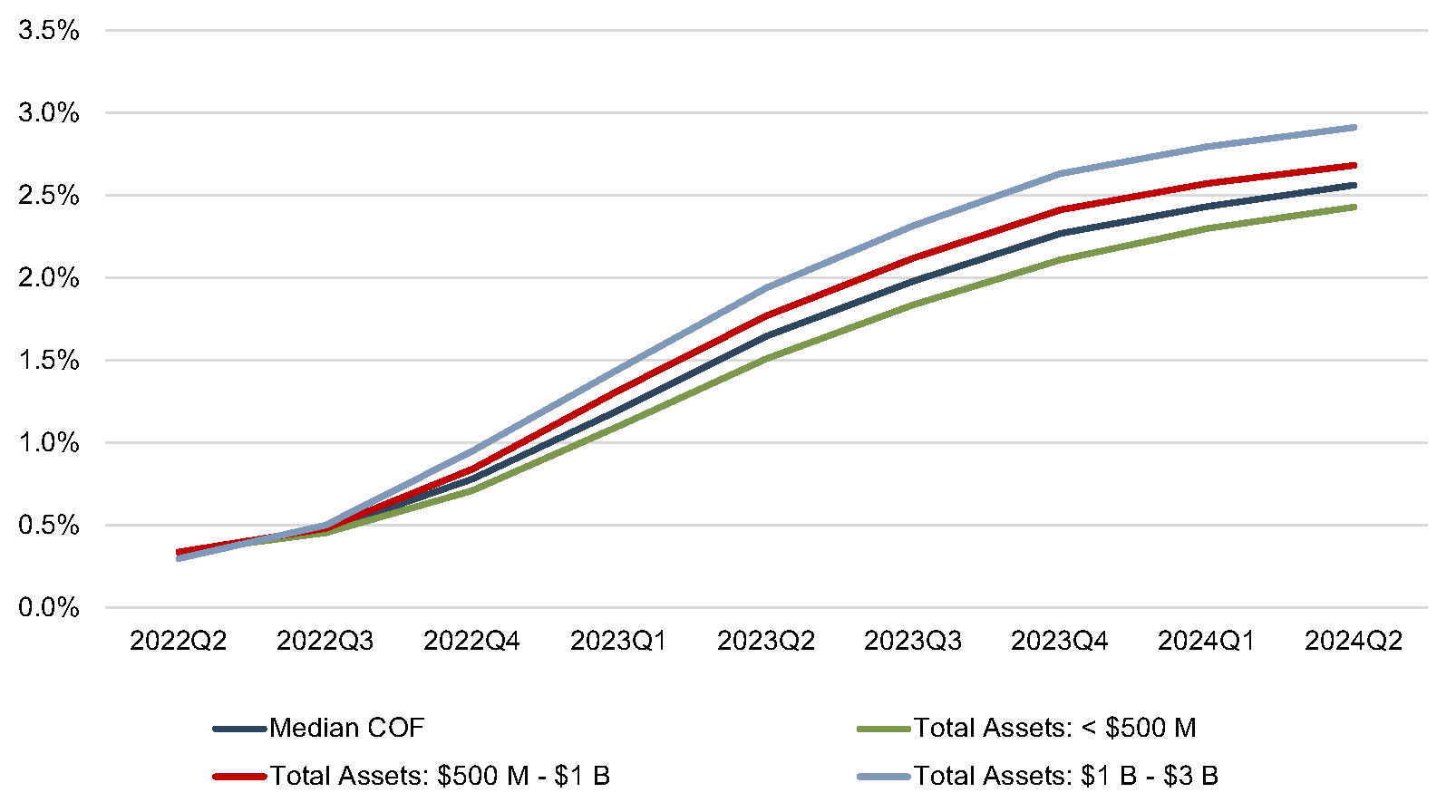

- Cost of Funds. Although many believe deposit rates have peaked, a possibility remains that deposit rates will not be as flexible on the way down. For example, notifications of lower rates may trigger some depositors, now accustomed to higher rates, to seek alternatives. Banks may need to weigh their desire to reduce deposit rates against the need to preserve deposit balances. As shown on Figure 3, in falling rate environments, the median cost of funds has tended to decrease at a slower rate than the fed funds target rate. However, interest rate beta is in part determined by the size of the financial institution, as evidenced by Figure 4.

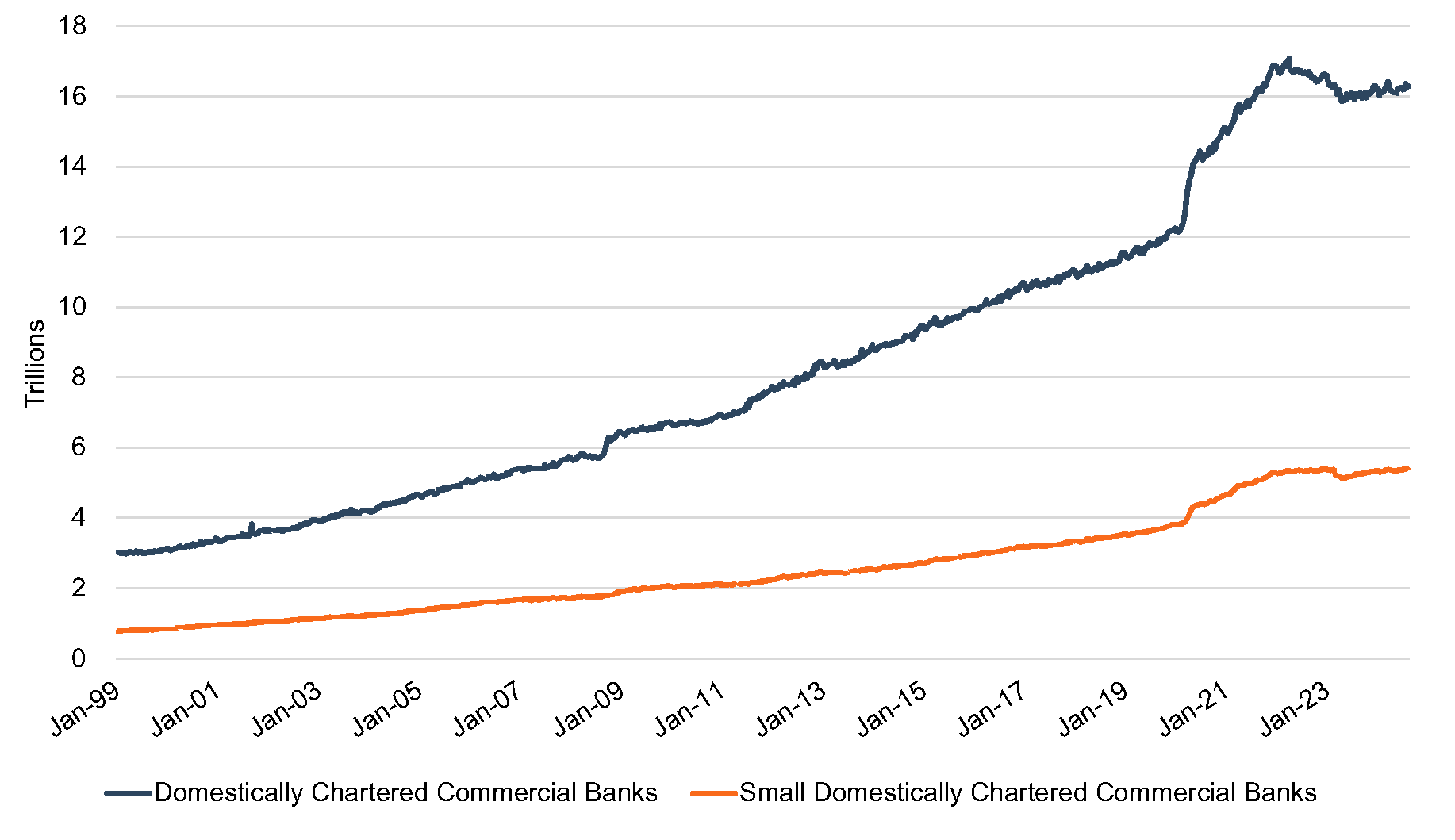

- Deposit Levels. In 2022, total industry deposits fell 1.1%, the largest annual decline on record.2 Last year at this time, less than half of respondents expected deposits to increase at their organization over the next 12 months. However, deposits have been relatively flat since this time last year. In the same survey for the second quarter of 2024, three out of five bankers expect deposits to grow over the next twelve months.3 All else equal, lower deposit runoff assumptions lead to higher indications of CDI value.

Figure 3: Median Cost of Funds as Compared to Target Fed Funds Rate

Source: S&P Capital IQ Pro

Figure 4: Cost of Funds by Asset Size – 2Q22 to 2Q24

Source: S&P Capital IQ Pro

Source: S&P Capital IQ Pro

Figure 5: Total Industry Deposits Per Federal Reserve H.8 Release

Source: S&P Capital IQ Pro

Source: S&P Capital IQ Pro

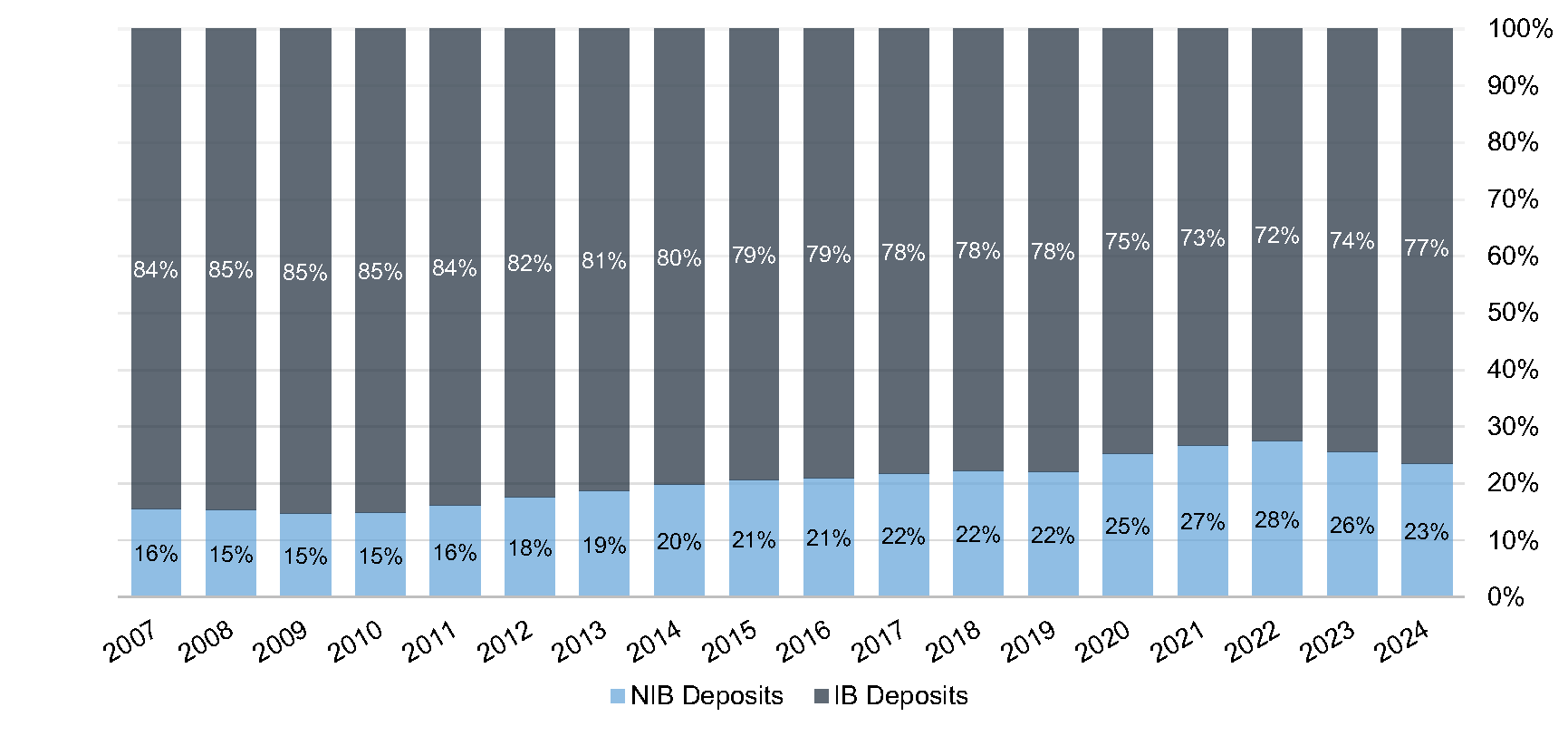

- Deposit Mix and Deposit Beta. Over the past decade, nationwide average deposit mix has shifted in favor of noninterest bearing deposits. In 2023 and 2024, this trend began to reverse in a higher interest rate environment. However, the deposit mix shift toward interest bearing deposits might not continue in a falling interest rate environment. As noninterest-bearing deposits have higher CDI values, this could be a mitigating factor for the anticipated decline in CDI values.

- Uncertain Rate Outlook. At present, the upside risks to inflation have diminished. Should recent positive inflation trends reverse, the Federal Reserve is likely to pause interest rate cuts or even increase rates again. Seven of the FOMC participants expect a further 25 basis point cut in 2024, while nine predict 50 basis points of additional cuts. Two predict no additional cuts, and one predicts a total of 75 basis points of cuts.

Figure 6: Deposit Mix Over Time

Source: S&P Capital IQ Pro

Source: S&P Capital IQ Pro

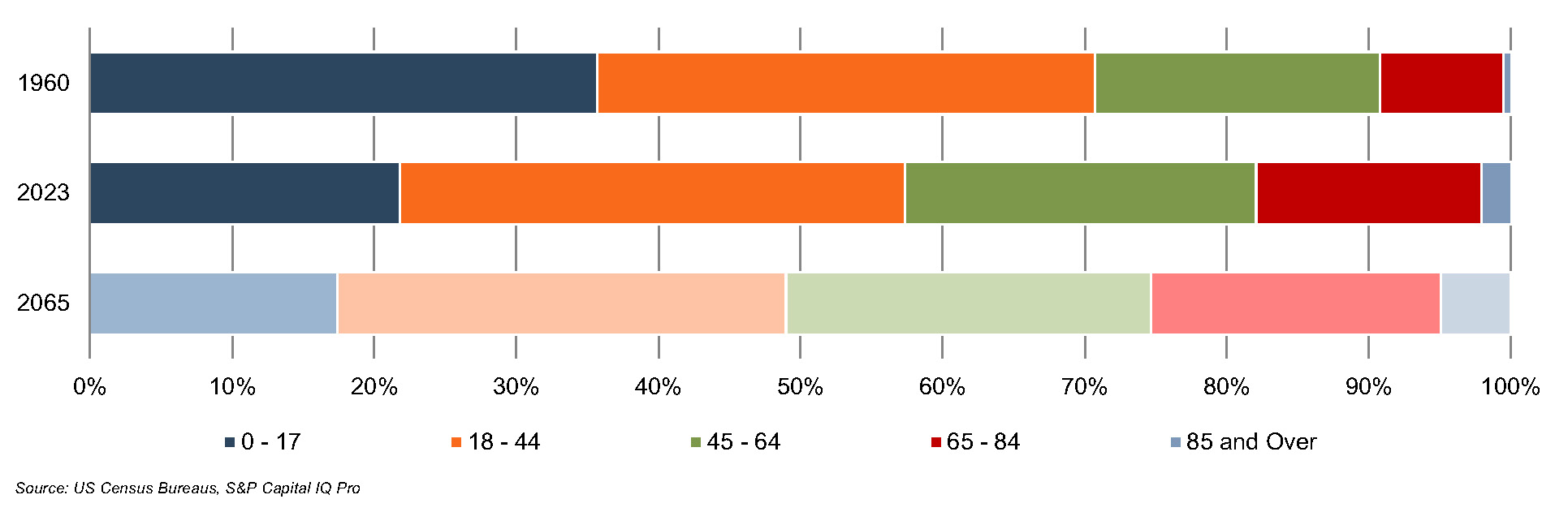

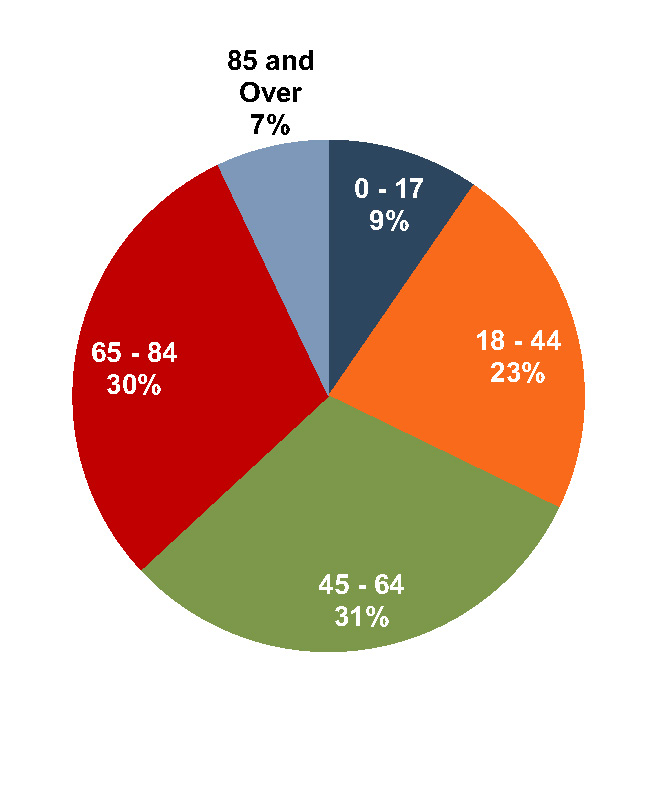

- Other Factors. More details within the deposit trial balance tend to provide more meaningful indications of depositor value – and this is especially important to consider on the front end of a deal. When possible, we like to see a customer relationship identifier, information on industry concentrations, more granular detail on account types, several years of deposit history, demographic details surrounding customer age and location, and average account balances over time.

Admittedly, this level of detail is not always feasible due to data limitations, but more detail contributes to a more comprehensive “story” of the deposit base. Before you can value the core deposit intangible asset, you need to begin by ascertaining which accounts and balances are “core”. Furthermore, sometimes a particular relationship might be core, but some or most of its balances at a particular point in time might not be.

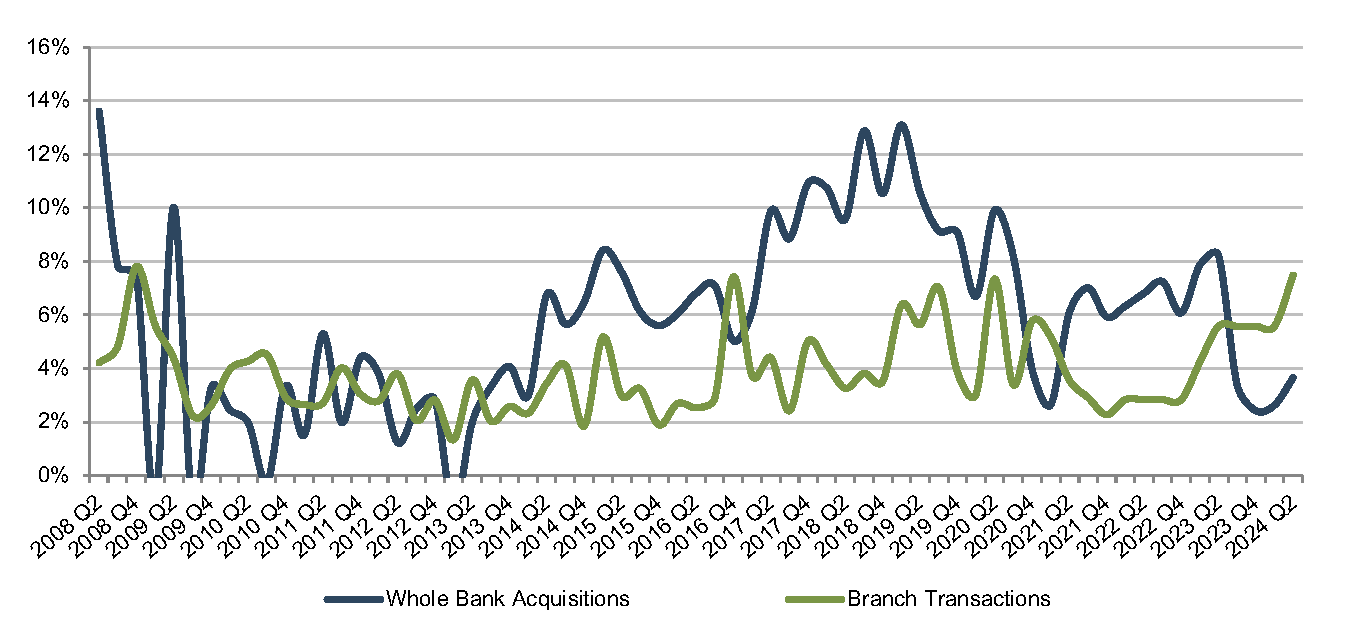

Trends In Deposit Premiums Relative To CDI Asset Values

Core deposit intangible assets are related to, but not identical to, deposit premiums paid in acquisitions. While CDI assets are an intangible asset recorded in acquisitions to capture the value of the customer relationships the deposits represent, deposit premiums paid are a function of the purchase price of an acquisition. Deposit premiums in whole bank acquisitions are computed based on the excess of the purchase price over the target’s tangible book value, as a percentage of the core deposit base.

While deposit premiums often capture the value to the acquirer of assuming the established funding source of the core deposit base (that is, the value of the deposit franchise), the purchase price also reflects factors unrelated to the deposit base, such as the quality of the acquired loan portfolio, unique synergy opportunities anticipated by the acquirer, etc. As shown in Figure 7, deposit premiums paid in whole bank acquisitions have shown more volatility than CDI values. Deposit premiums were in the range of 6% to 10% from 2015 to 2022, although this remained well below the pre-Great Recession levels when premiums for whole bank acquisitions averaged closer to 20%. Net interest margin pressure—caused by assets originated at low rates during the pandemic and deposits that proved more rate sensitive than expected—resulted in deposit premiums in 2024 falling to levels last seen in the Great Financial Crisis.

Additional factors may influence the purchase price to an extent that the calculated deposit premium doesn’t necessarily bear a strong relationship to the value of the core deposit base to the acquirer. This influence is often less relevant in branch transactions where the deposit base is the primary driver of the transaction and the relationship between the purchase price and the deposit base is more direct. Figure 8 presents deposit premiums paid in whole bank acquisitions as compared to premiums paid in branch transactions.

Deposit premiums paid in branch transactions have generally been less volatile than tangible book value premiums paid in whole bank acquisitions. Only two branch transactions with reported premium data have occurred year-to-date in 2024. For those transactions, the deposit premiums were 7.5% and 4.0%. The lack of branch transactions, though, is indictive of their value. With high short-term funding costs and tight liquidity, few banks have been willing to part with stable, low-cost core deposits.

Figure 7: CDI Recorded vs. Deposit Premium

Source: S&P Capital IQ Pro

Source: S&P Capital IQ Pro

Figure 8: Average Deposit Premiums Paid

Source: S&P Capital IQ Pro

Source: S&P Capital IQ Pro

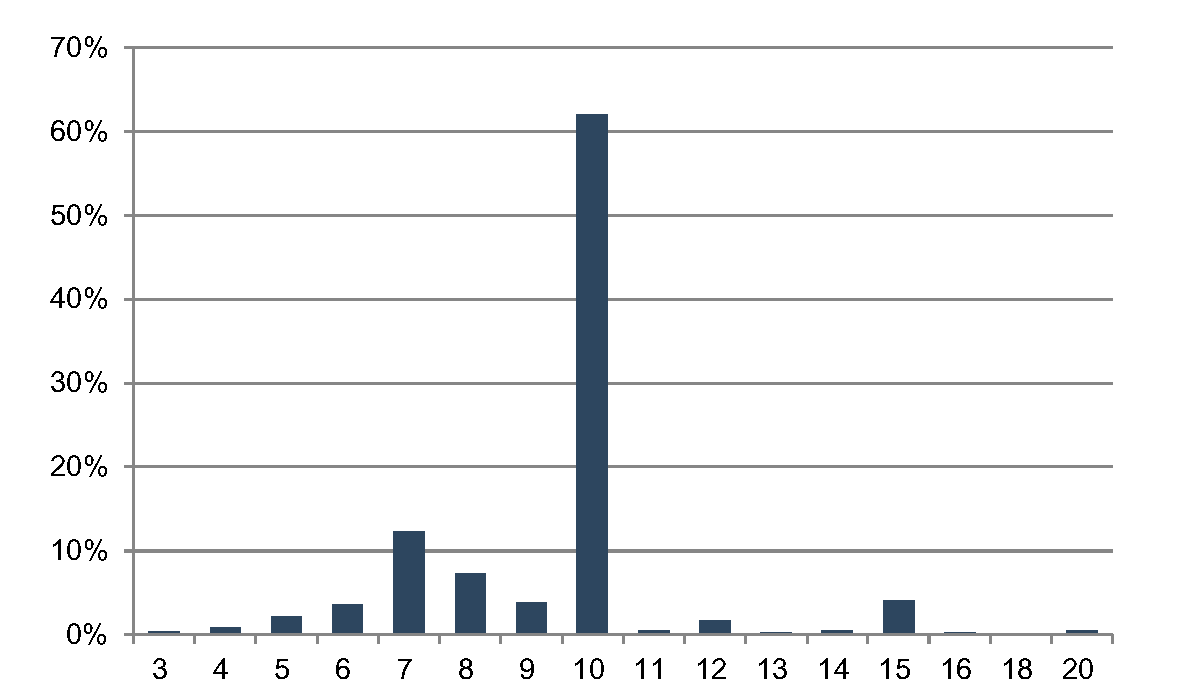

Accounting For CDI Assets

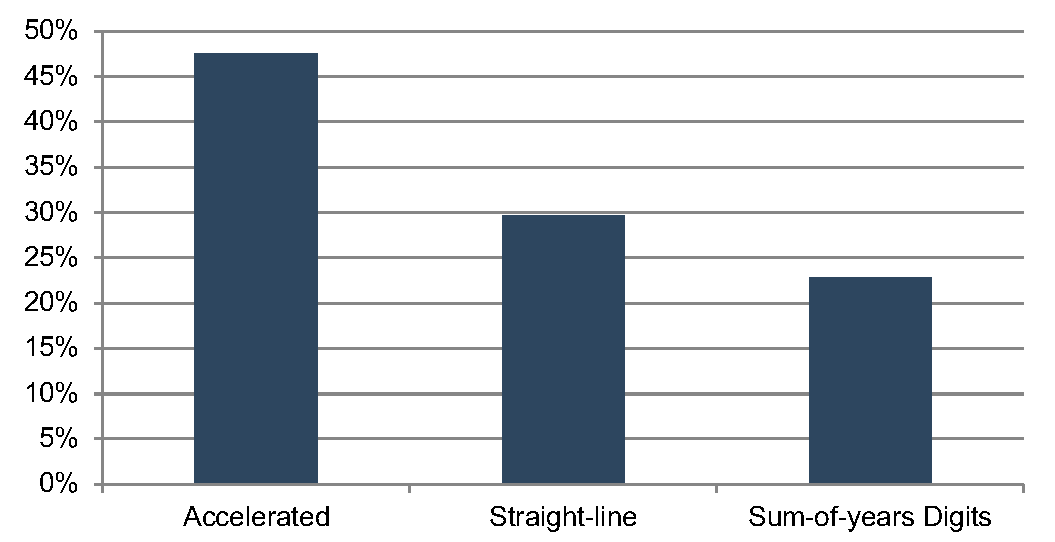

Based on the data for acquisitions for which core deposit intangible detail was reported, a majority of banks selected a ten-year amortization term for the CDI values booked. Less than 10% of transactions for which data was available selected amortization terms longer than ten years. Amortization methods were somewhat more varied, but an accelerated amortization method, including the sum-of-the-years digits method, was selected in approximately two-thirds of these transactions.

For more information about Mercer Capital’s core deposit valuation services, please contact a member of our Depository Institutions team.

Figure 9: Selected Amortization Term (Years)

Source: S&P Capital IQ Pro

Figure 10: Selected Amortization Method

Source: S&P Capital IQ Pro

Source: S&P Capital IQ Pro

1 S&P Capital IQ Pro defines core deposits as, “Deposits in U.S. offices excluding time deposits over $250,000 and brokered deposits of $250,000 or less.”

2 Defined by the Federal Reserve as domestically chartered commercial banks.

3 According to S&P Capital IQ Pro’s US Bank Outlook Survey

Real Estate and the Family Business in Divorce

Travis Harms recently wrote a piece for our Family Business Director Blog about the family business’ investment in real estate. Below, we have adapted his piece for business owner clients going through a divorce.

As the pandemic recedes further into the rearview mirror, long-term business consequences continue to reverberate through the economy. In addition to recalibrating expectations among domestic manufacturers, foreclosures on distressed commercial real estate are accelerating.

For many business owners and their spouses, the marital net worth may be concentrated in the value of the business. Furthermore, the company’s real estate can be a significant portion of this value or may represent additional value. The lingering pandemic-induced weakness in commercial real estate values may encourage families to re-evaluate their real estate strategies, though this varies by asset class, use, and geography among many other considerations. Re-evaluating real estate strategies is particularly necessary for couples seeking to equitably divide assets in a marital estate pursuant to a divorce.

Below we highlight three real estate strategies we often see for those who own and operate a business.

Real estate strategy #1 – Operating business owns real estate needed for operations

This strategy is often the default strategy for enterprising families.

- This approach has the virtue of simplicity. When additional productive assets are needed to take advantage of growth opportunities, the company acquires them, whether those assets consist of machinery & equipment or real estate.

- Owned real estate provides the operating business with leverage capacity. Lenders take comfort in real estate as collateral, so businesses that accumulate operating real estate on their balance sheets will likely have greater borrowing capacity when attractive investment opportunities arise.

- All else equal, an operating business that owns real estate is probably less risky than one that does not. Real estate holdings are likely to have alternative future uses outside the business and carry less risk than intangible assets, goodwill, and other assets that are specific to an operating business.

- Real estate offers the prospect of capital appreciation. Rolling stock, production equipment, and other operating assets depreciate and lose value over the long term. In contrast, investments in operating real estate can provide opportunities for capital appreciation in addition to the value created through operating the business.

Real estate strategy #2 – Operating business leases real estate needed for operations from a third party

Instead of purchasing real estate for operations, some family businesses elect to lease facilities needed for operations from unrelated third parties.

- This strategy preserves the greatest flexibility for the operating business. Beyond the remaining term of the lease agreement, the operating business is not committed to the real estate from which it operates. As strategies and market opportunities evolve, the operating business’s real estate needs are likely to evolve as well.

- Leasing real estate from a third party allows management of the operating business to focus on running the business. Call it “core competency” or what have you: developing & managing real estate well requires a different skill set than running an operating business. Leasing the real estate needed for operations rather than owning allows the management team to focus on what they do best.

- Leasing can boost return on invested capital and shareholder returns. By reducing the amount of capital committed to the business, lessees can realize higher returns on invested capital. Of course, return follows risk, so the higher expected returns come from bearing greater risk.

- This strategy avoids the risk of falling property values weighing on business returns. While real estate values do often go up, appreciation is not guaranteed. As noted in the second article linked in the introduction, commercial real estate values are currently under pressure in many sectors and markets. For lessees, that is someone else’s problem.

Real estate strategy #3 – Operating business leases real estate needed for operations from a related party

This strategy represents a “hybrid” of the other two strategies. Under this approach, the operating real estate is owned by a related family entity and leased to the operating business.

- This approach can add governing complexity. The real estate entity will need its own governance mechanism, specifically a lease agreement defining the arrangement.

- Separating ownership of operating real estate from the business can allow families to offer a more tailored risk and return profile to family members. Not all family members have identical return objectives and risk tolerances, and housing operating real estate in a separate entity can accommodate a wider range of shareholder preferences.

- While most divorcing couples prefer not to be economically tied to their spouse post-divorce, this is not always attainable. Splitting the operating business and the real estate can potentially represent an amicable solution for both parties. In this case, significant post-marital efforts increasing the value of the core operating business accrue to the “in-spouse”, while the current rental income and passive capital appreciation of the real estate accrue to the “out-spouse” who is not able to meaningfully improve the value of the operating business post-divorce.

Intentional or not, all small business owners have a real estate strategy. An outside perspective can be helpful if your real estate strategy is due for a simple refresh or a wholesale reconsideration, in the context of a divorce or not. Give one of our senior professionals a call today to discuss your situation in confidence.

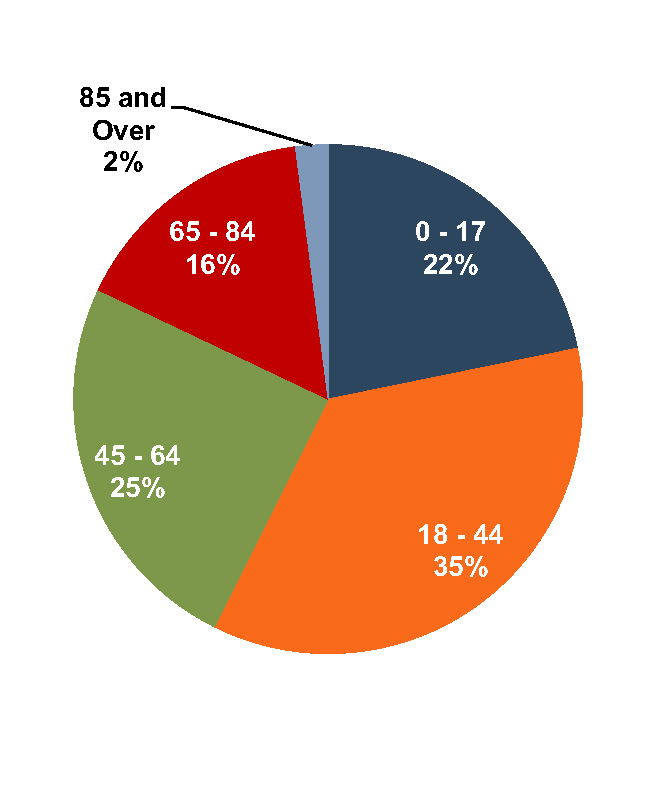

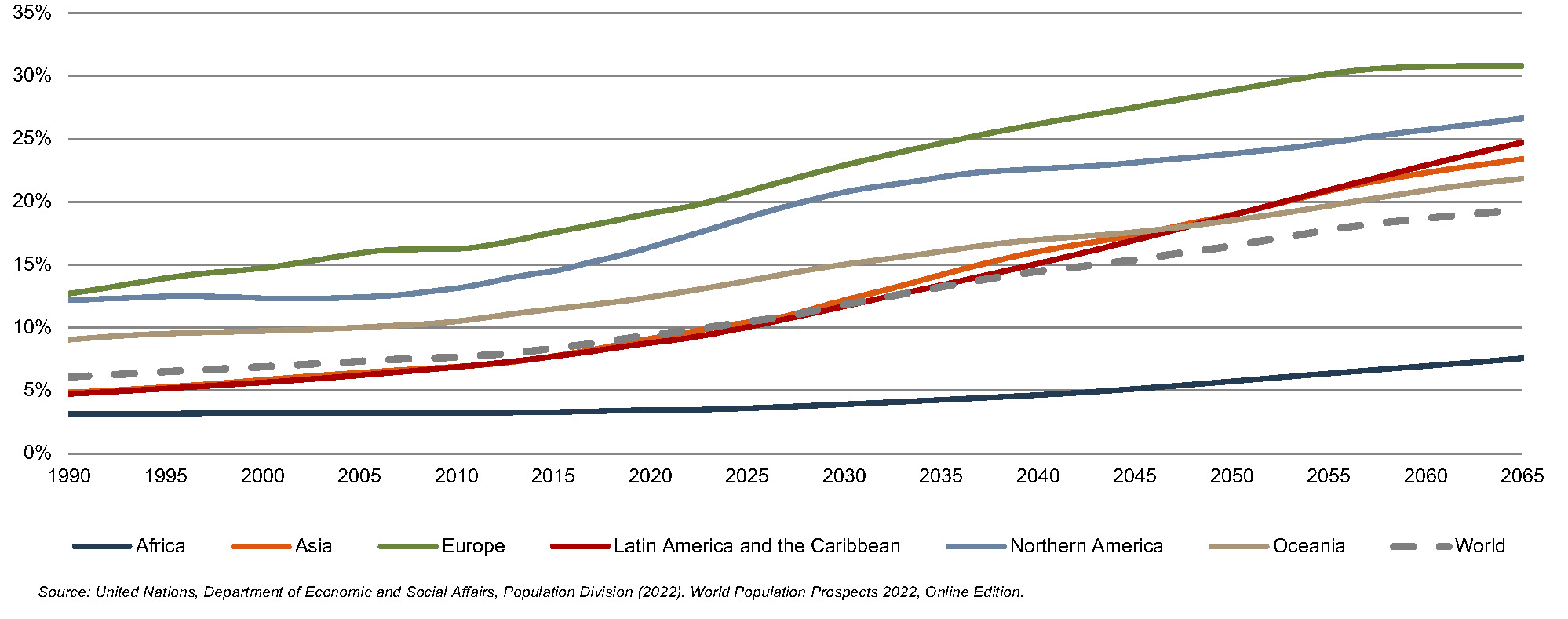

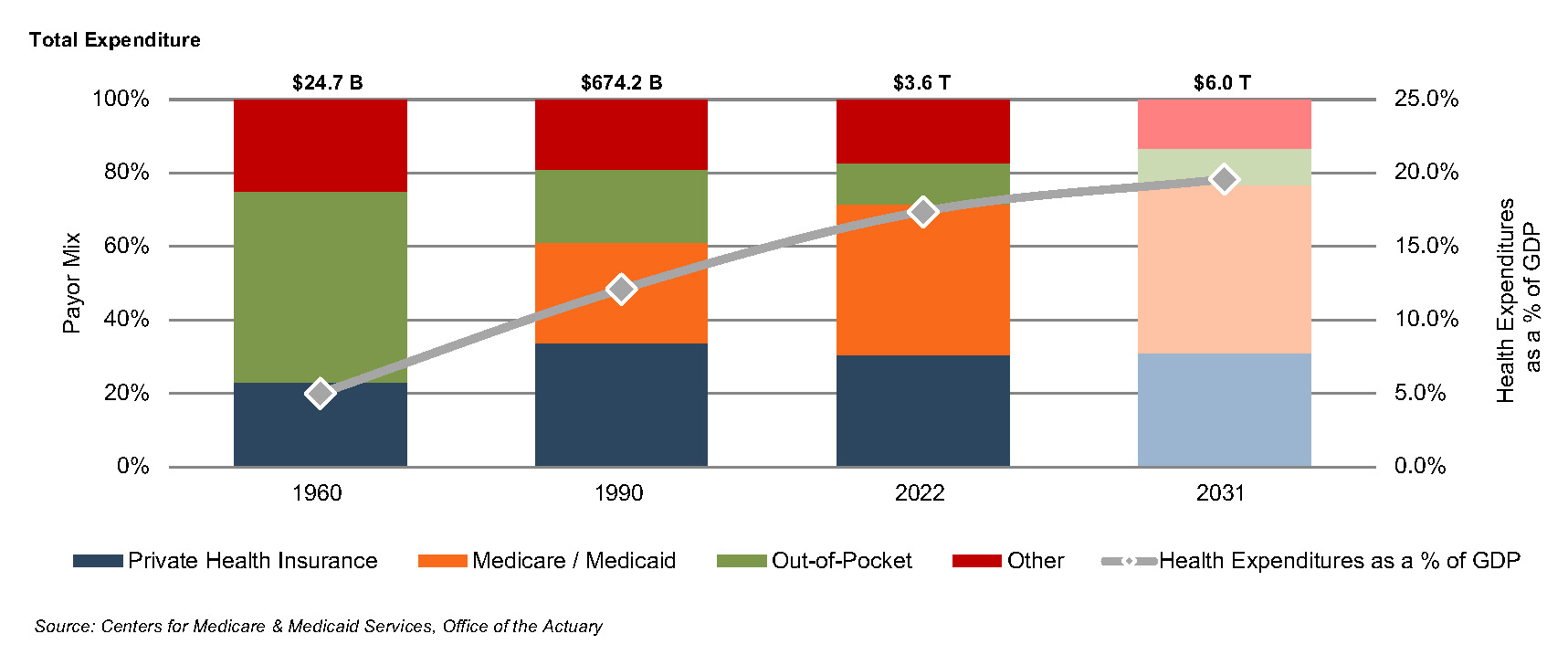

Are Retirement Plans an Underappreciated Growth Opportunity for RIAs?

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (“ERISA”) of 1974, which established minimum standards for the protection of retirement plan participants and laid the groundwork for the development of the 401k plan a few years later. These events set in motion a multi-decade shift in the nature of retirement assets. Fifty years ago, defined benefit (DB) plans were the norm; now, DB plans have been largely superseded in the private sector by defined contribution (DC) plans, of which the 401(k) plan is the most prominent vehicle.

Scale of Retirement Market

Today, there’s about $7.4 trillion in assets held in 401(k)s across some 700 thousand plans and 70 million participants. There’s an additional $3.1 trillion held in other (non-401(k)) DC plans, and an additional $13.6 trillion held in IRAs (which are often funded by rolled-over 401(k)s). Big numbers, but they’re only a small portion of the roughly $128 trillion in aggregate AUM managed by some ~15,000 RIAs across the U.S.

Defined contribution plan assets are an increasingly relevant part of the financial picture for clients

While the retirement market remains small relative to total wealth managed by RIAs, 401(k) assets and other DC plan assets are an increasingly relevant part of the financial picture for clients. The long transition from DB to DC plans has generated higher growth in DC plan assets than other assets. The Pension Protection Act of 2006 further amplified this trend by increasing uptake through endorsement of automatic enrollment, automatic contribution escalation, and default investments. As a result, the share of total household net worth held in DC plans like 401(k)s has doubled from about 5% in 1990 to about 10% today—a trend which is likely to continue given the current legislative backdrop.

Convergence of Retirement and Wealth

The growth in 401(k) assets and rollovers into IRAs is a multi-decade bullish tailwind for RIAs that can take advantage of it, either by advising plans directly or by advising individuals on their 401(k) assets. Recently, Envestnet highlighted retirement as an underappreciated growth opportunity for advisors in its Trends to Watch in 2024 report, citing challenges in accessing workplace retirement plans for many SMBs, regulatory tailwinds such as SECURE Act 2.0, and technology innovations that are making it easier for non-retirement-expert advisors to offer retirement solutions.

Offering defined contribution services allows advisors to expand their suite of offerings and access a client segment with an attractive growth profile

Offering DC services allows advisors to expand their suite of offerings and access a client segment with an attractive growth profile. Relative to a “typical” wealth management client that is withdrawing assets to fund their lifestyle, 401(k) assets have a number of built-in growth levers that can fuel growth for RIAs: new plans continue to be established, clients continue to contribute assets, contributions grow with wage growth or with escalating contribution percentages, and underlying assets grow with the market.

Additionally, there’s an increasing focus in the industry on holistic financial planning, which necessitates taking into account a client’s retirement assets and consideration of the asset allocation, tax attributes, and other features like RMDs associated with those accounts. Thus, DC service offerings allow advisors to offer more comprehensive advice to clients by addressing an increasingly relevant component to the client’s financial picture.

Beyond deepening relationships with existing clients, offering DC services opens doors to developing connections with SMB business owners (often HNW individuals) and HNW plan participants. The connections formed through DC services can create a valuable pipeline to mine for new HNW advisory clients.

This is not to say that all RIAs should set out to become retirement plan advisors. There are potential downsides as well, like fees that are often lower and more exposure to fiduciary liability. But a growing wealth segment in an industry that often struggles with organic growth is a trend worth watching closely.

About Mercer Capital

We are a valuation firm that is organized according to industry specialization. Our Investment Management Team provides valuation, transaction, litigation, and consulting services to a client base consisting of asset managers, wealth managers, independent trust companies, broker-dealers, PE firms and alternative managers, and related investment consultancies.

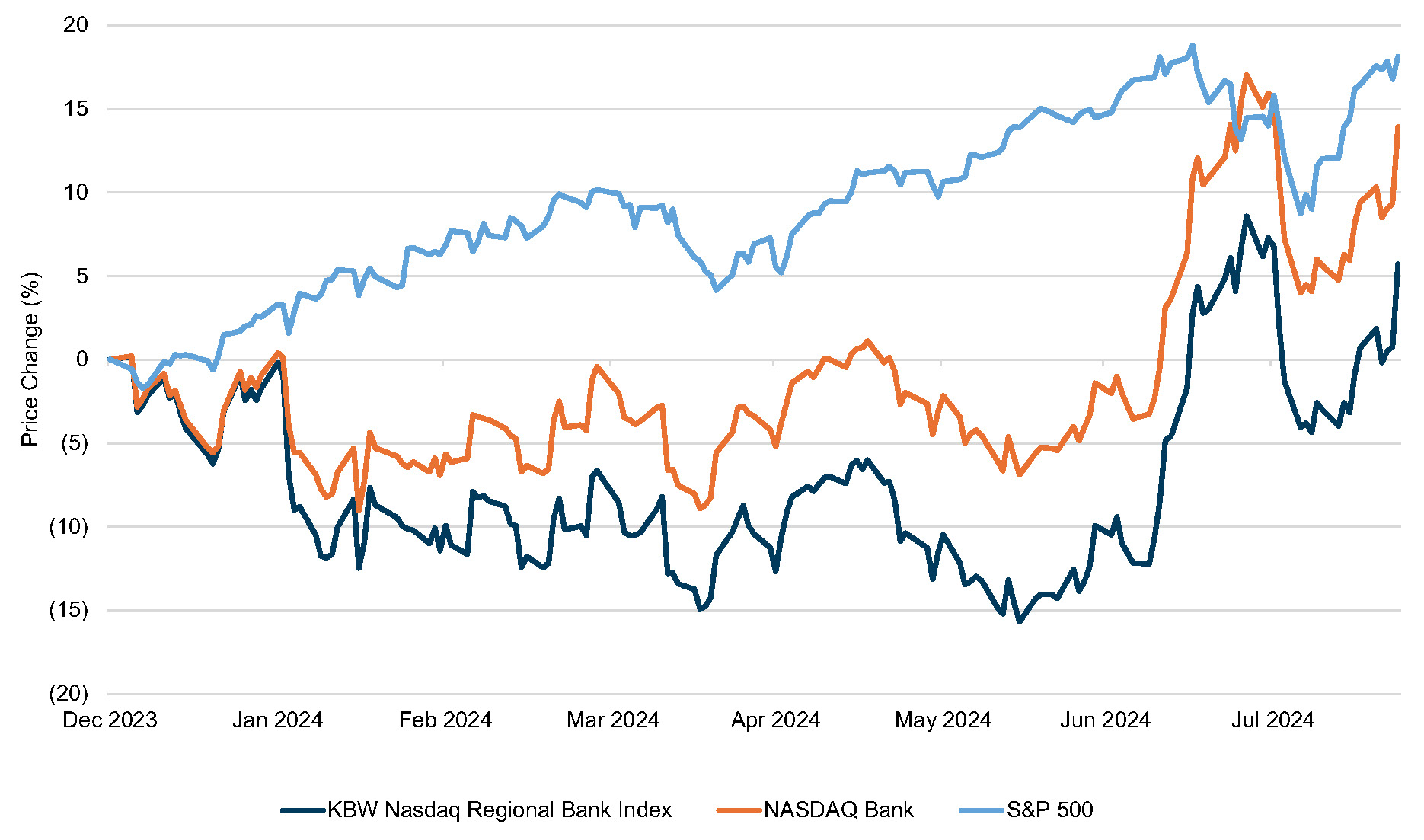

Equity Capital Raises

The banking zeitgeist is evolving: 2023 was about a liquidity crisis that claimed three banks who were members of the S&P 500; 2024 is shaping up as the year of capital raises by a handful of regionals to deal with the aftermath of the Fed’s ultra-low-rate environment.

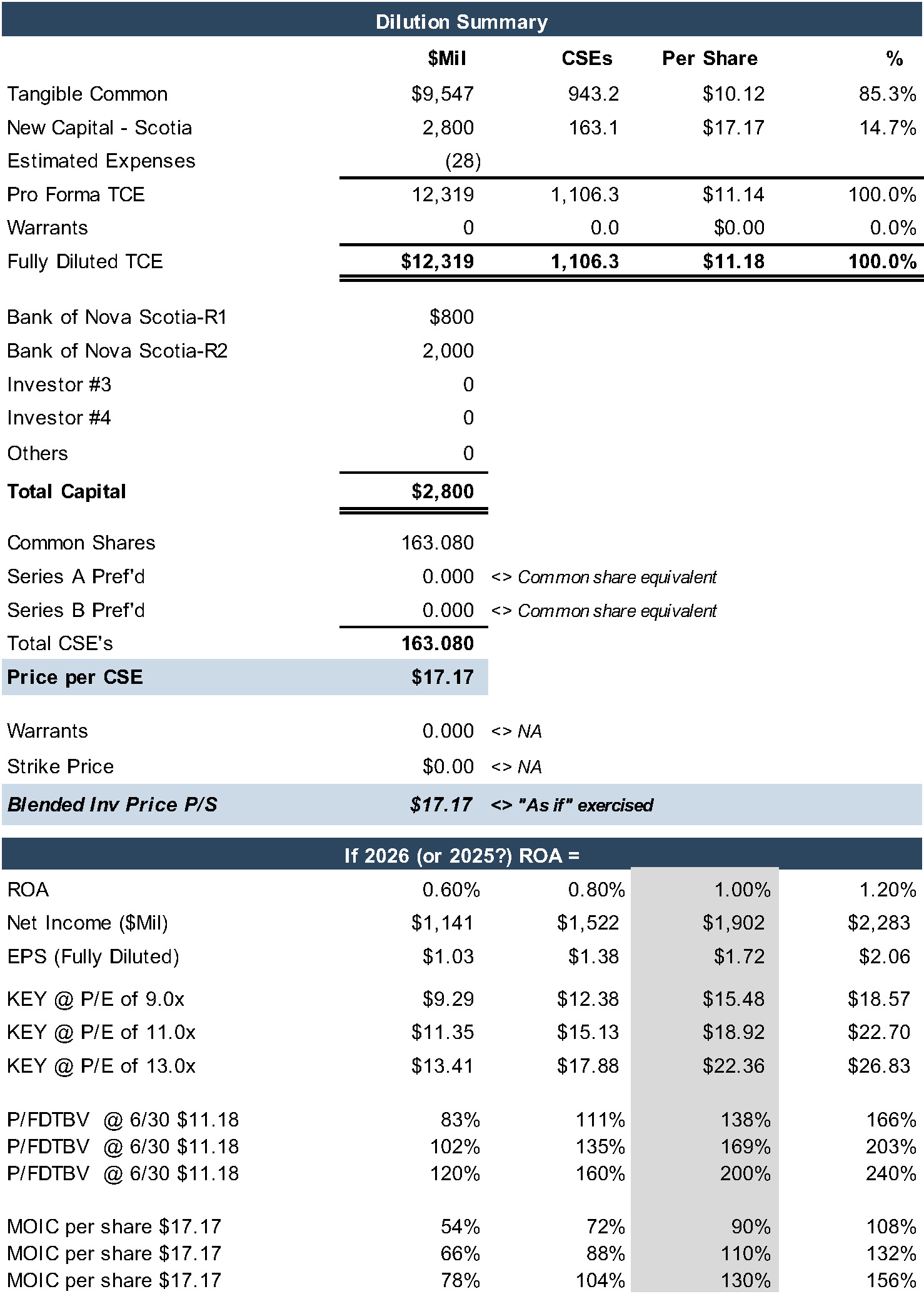

KeyCorp (NYSE:KEY) was the latest bank to raise capital. The Bank of Nova Scotia (TSX:BNS) will purchase ~163 million newly issued common shares in a two-step transaction that once consummated will result in Scotia owning 14.9% of the common shares.

The $17.17 per share issue price equates to:

- 15% premium to the ten-day volume weighted average price through August 9;

- ~1.50x pro forma tangible book value; and

- 10.8x consensus 2025 EPS estimate.

The market was surprised by the investment because KEY’s and KeyBank’s common equity tier 1 ratios were 10.5% and 12.6% respectively as of June 30, 2024. However, the respective tangible common equity ratios were 5.2% and 6.9% given sizable unrealized losses in the AFS bond portfolio and receive fix/pay variable swaps book. KEY has earmarked about one-half the capital to absorb losses from restructuring the balance sheet.

Unlike the New York Community Bancorp (NYSE:NYCB) and First Foundation (NASDAQ:FFWM) capital raises that occurred at significant discounts to the market and tangible BVPS, KEY’s shares traded up on the announcement. Investors took the investment price as a form of validation of KEY’s credit marks, plus there is the potential for the “strategic minority” investment to become a control position via acquiring the remaining common shares one day.

Figure 1: Bank of Nova Scotia Equity Investment in KeyCorp

Figure 2: KEYCORP Pro Forma Balance Sheet

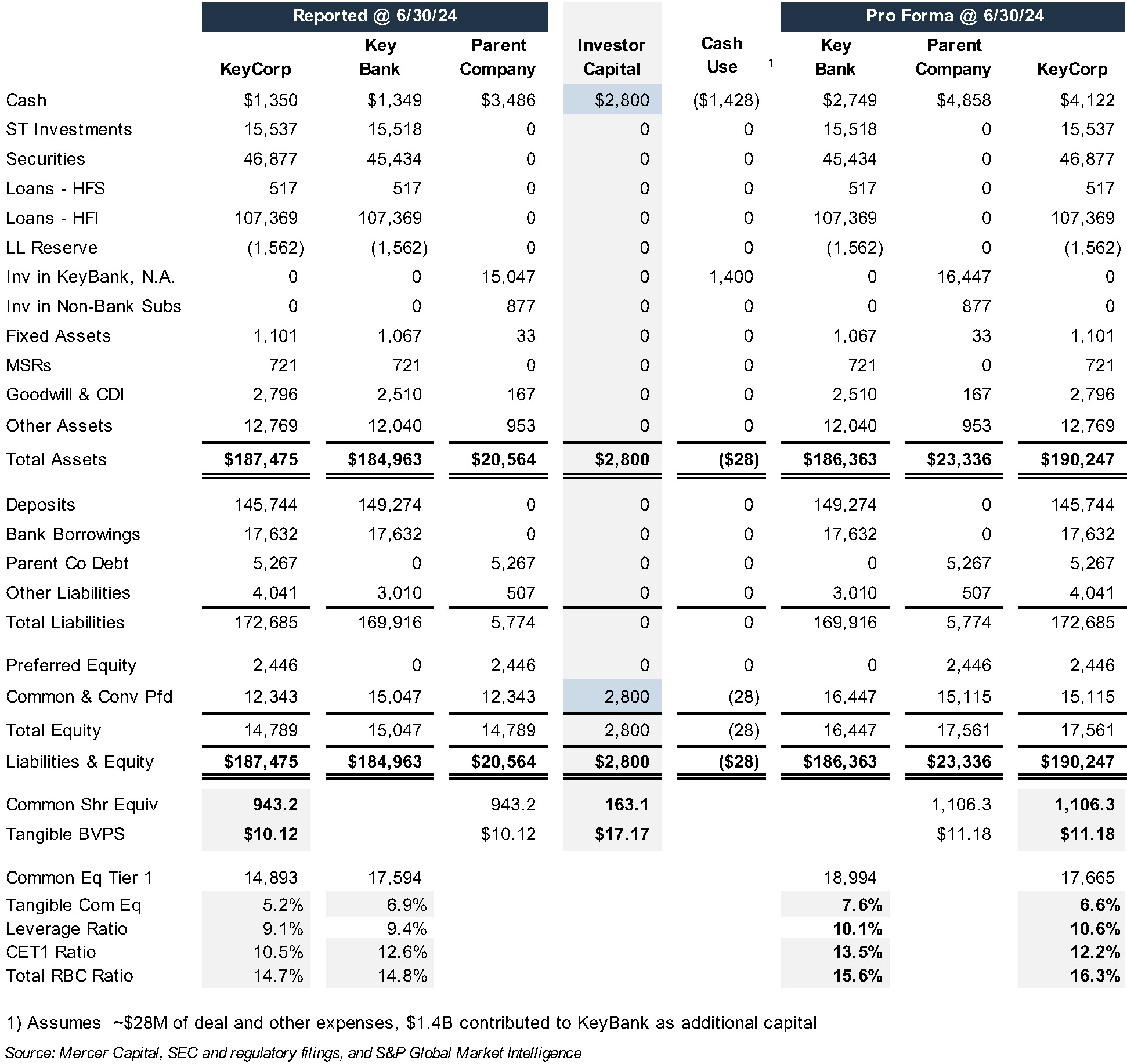

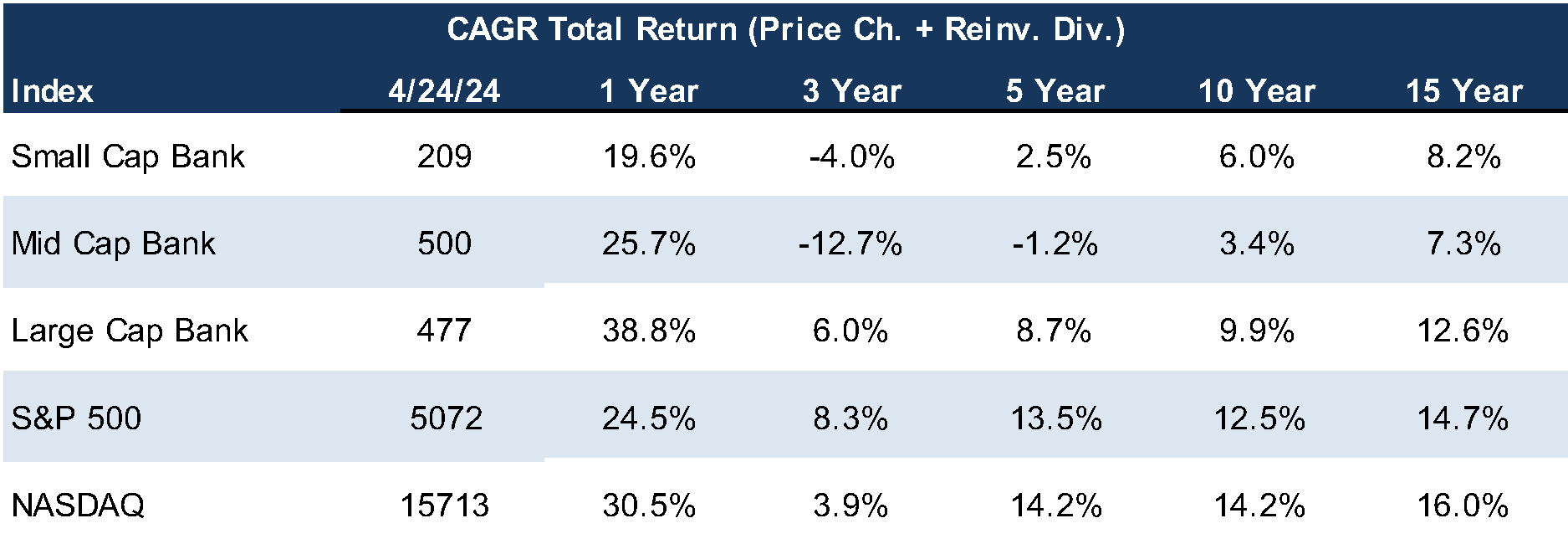

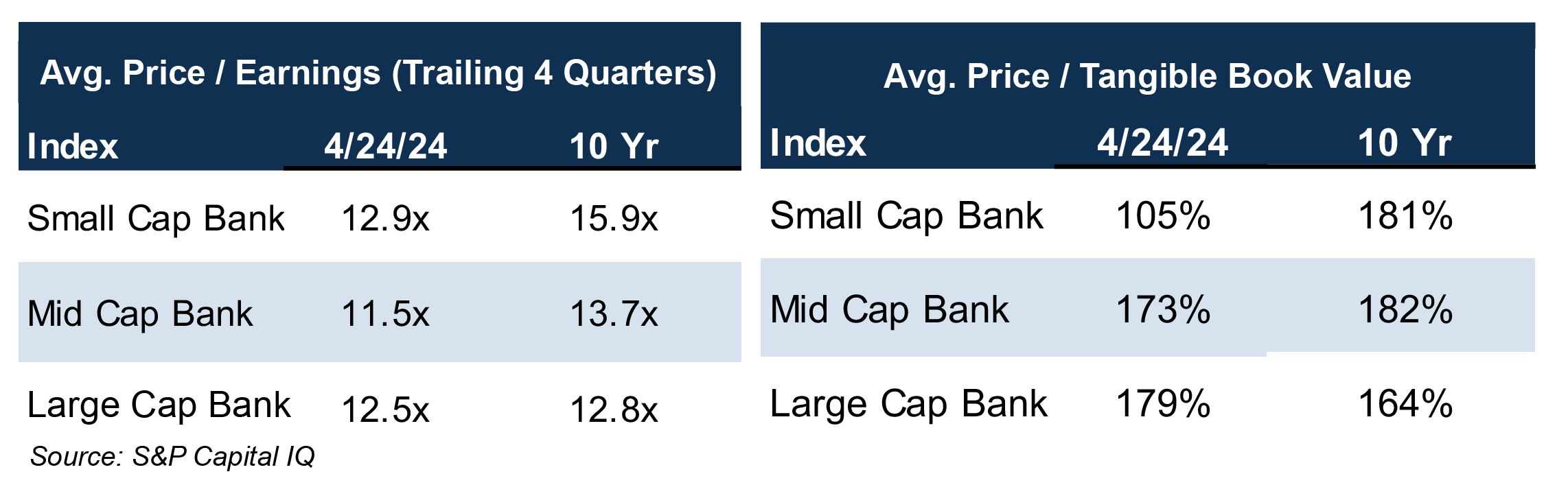

2024 Mid-Year Market Update

Year-to-date through August 23, the Nasdaq Bank Index and the KBW Nasdaq Regional Bank Index appreciated by 14% and 6%, respectively, compared to 18% appreciation by the S&P (see Figure 1). Through June, bank stocks were flat to down from year-end 2023 but rallied in July to outperform the broader market with the Nasdaq Bank Index and the KBW Regional Bank Index appreciating by 17% and 19%, respectively, compared to 1% appreciation for the S&P in the month of July.

After a period of underperformance due to earnings pressure from rising rates and falling margins, banks rallied strongly during the reporting of 2Q24 earnings in July as it became apparent NIMs for most banks had or soon would stabilize and prospectively widen as the Fed moves to reduce short-term policy rates.

Figure 1: Index Performance (12/31/2023 – 8/23/2024) Source: S&P Capital IQ Pro

Source: S&P Capital IQ Pro

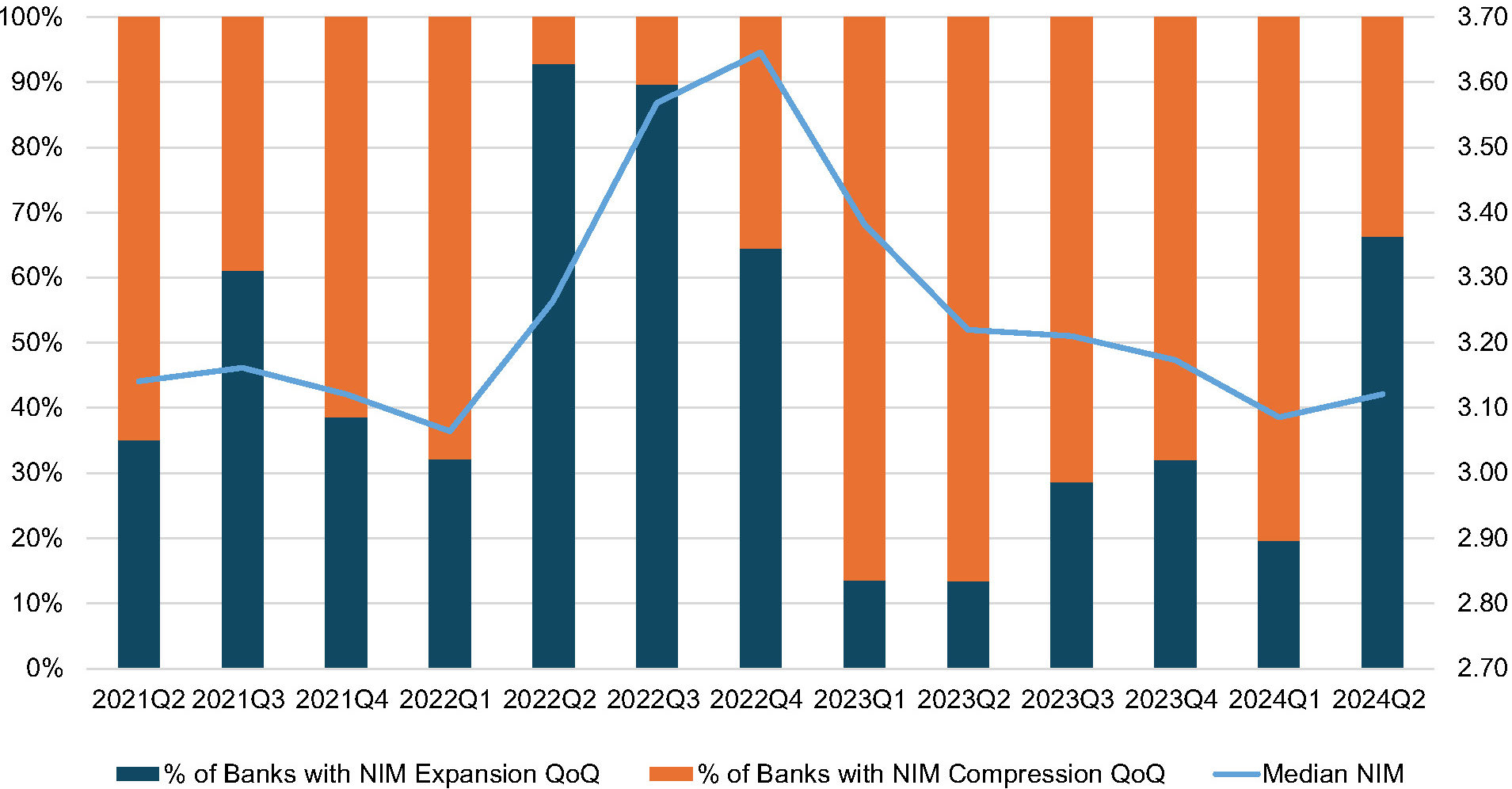

After steadily declining from a peak of 3.65% in the last quarter of 2022, the median net interest margin for all banks traded on the NYSE and Nasdaq widened by 3 bps in 2Q24 compared to 1Q24. Furthermore, as shown in Figure 2, 66% of all banks reported net interest margin expansion quarter-over-quarter, compared to just 20% in the first quarter of the year. Margin improvement was less prevalent for the biggest banks as only 32% of banks with assets over $100 billion reported net interest margin expansion in 2Q24, and the group as a whole reported median net interest margin compression of 3 bps (see Figure 3).

Figure 2: Trend in Median Net Interest Margin & QoQ Change in NIM

Source: S&P Capital IQ Pro, Mercer Capital Research

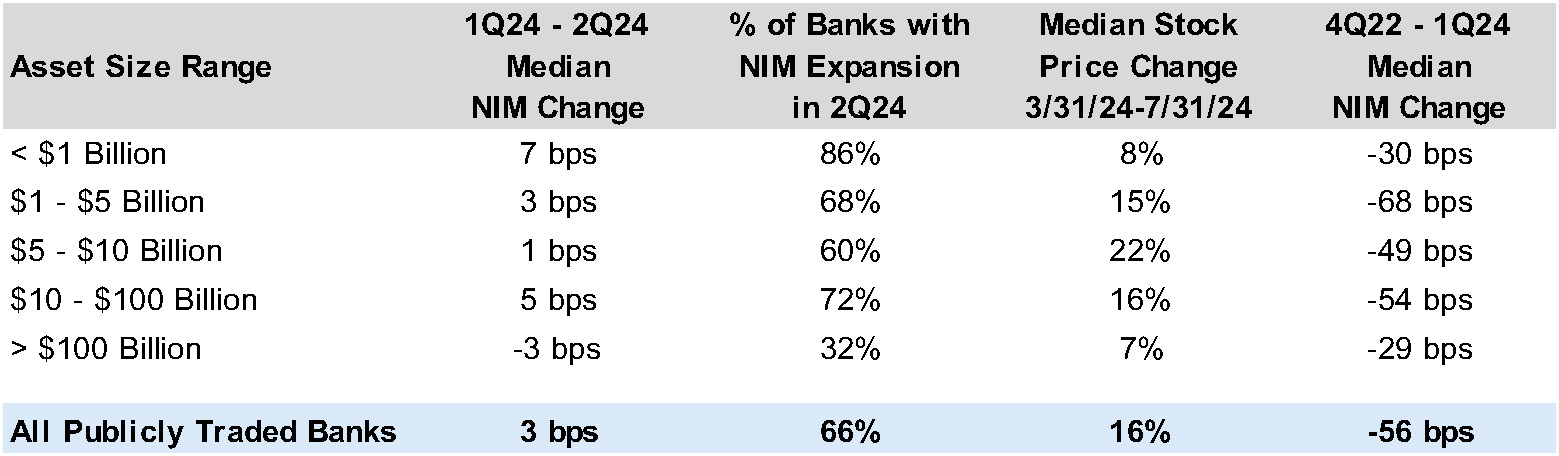

Stock price appreciation was greatest for the banks with total assets between $1 billion and $100 billion, in part reflecting investor optimism for earnings improvement for banks that faced the most margin compression from 4Q22 to 1Q24.

As shown in Figure 3, banks with assets less than $1 billion or greater than $100 billion reported stock price appreciation of 7%-8% from March 31, 2024 to July 31, 2024 compared to a 16% median increase for all banks.

Figure 3: Change in Net Interest Margin by Asset Size Range Source: S&P Capital IQ Pro

Source: S&P Capital IQ Pro

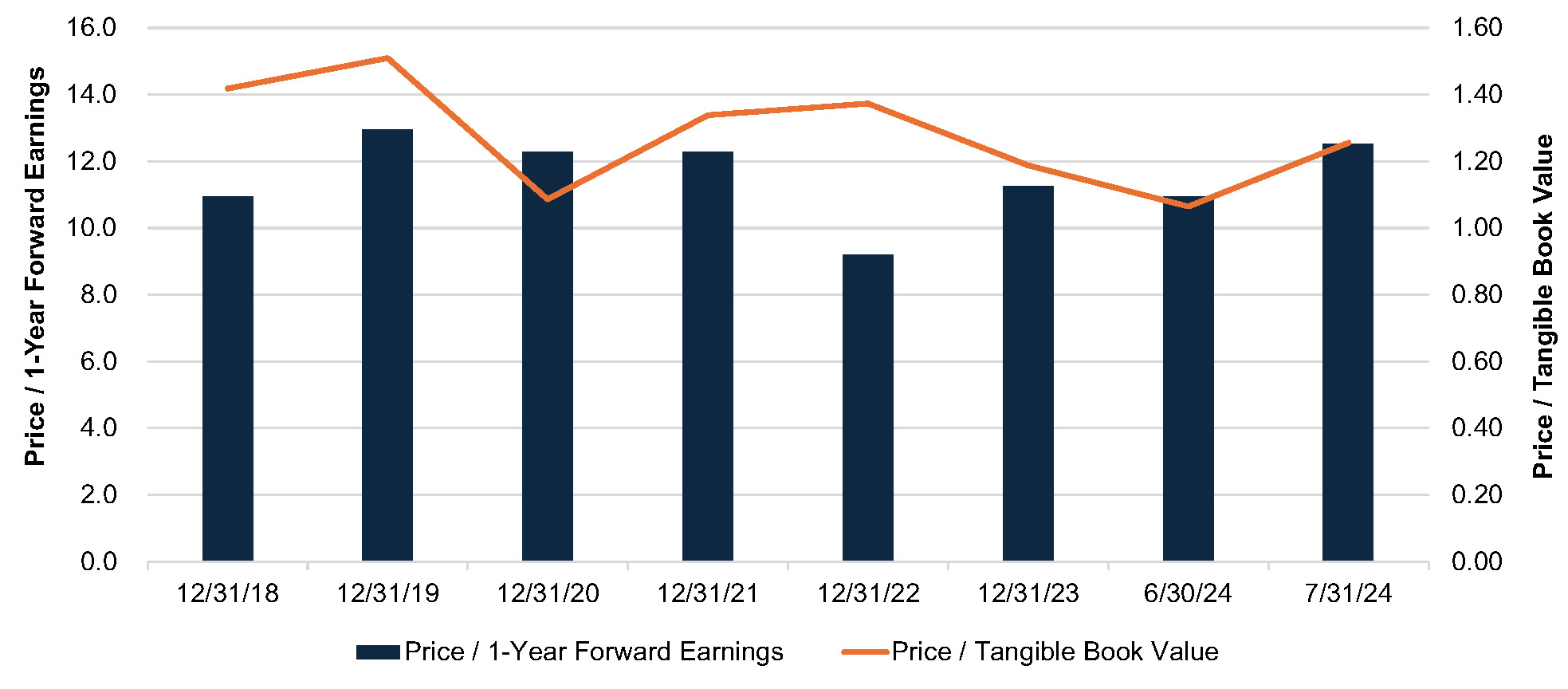

As illustrated in Figure 4, valuation multiples increased significantly with the rally in stock prices in July. Publicly traded banks with assets between $1 and $15 billion reported a median price/one year forward earnings multiple of 12.5x and a price/tangible book value multiple of 1.26x as of July 31, 2024, up from 10.9x and 1.06x as of June 30. In addition to higher forward P/Es, Analysts’ estimates for 2024 EPS were 12% higher as of July 31 compared to estimates for 2024 EPS available as of year-end 2023.

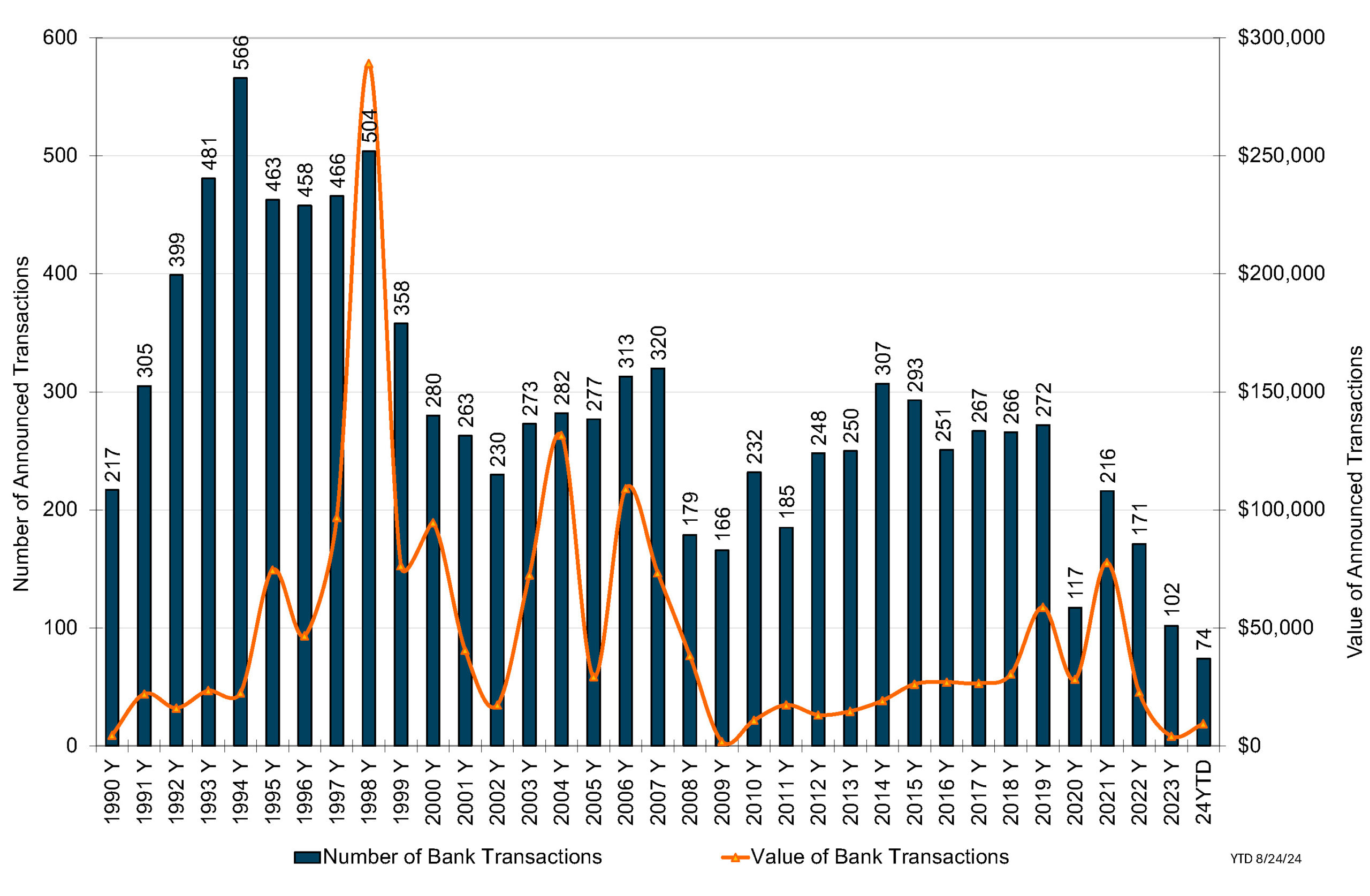

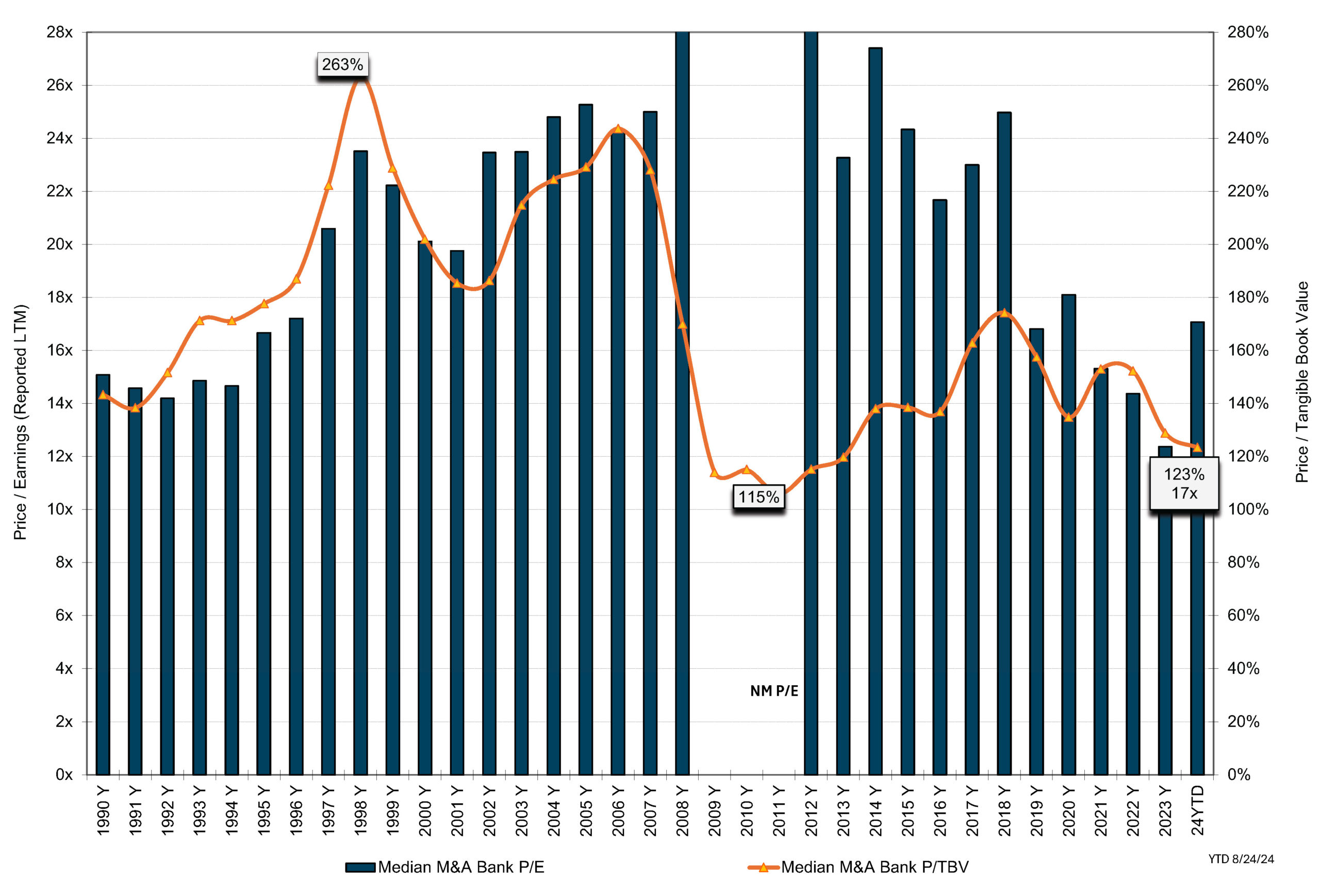

According to data provided by S&P Capital IQ Pro, there were 74 announced M&A transactions through August 24, compared to 102 announced transactions for the entirety of 2023. Notably, aggregate deal volume reached $9.4 billion, which exceeds the $4.2 billion in announced deals in all of 2023 as shown in Figure 5. After a period of subdued activity, the bank M&A market is showing signs of recovery. Three deals valued at over $1 billion have been announced in 2024 compared to just one in 2022 and 2023, and the median P/E multiple increased from 12.4x in 2023 to 17.1x in 2024.

Figure 4: Pricing Multiples (Banks with Assets between $1-$15 Billion) Source: S&P Capital IQ Pro, Mercer Capital Research

Source: S&P Capital IQ Pro, Mercer Capital Research

Figure 5: Deal Value and Volume Source: S&P Capital IQ Pro

Source: S&P Capital IQ Pro

Figure 6: Long-Term Trend in Pricing Multiples Source: S&P Capital IQ Pro

Source: S&P Capital IQ Pro

After a tumultuous period for the banking industry marked by bank failures, liquidity concerns, margin pressure, depressed valuations, and subdued M&A activity, the outlook for the remainder of 2024 is cautiously optimistic. EPS estimates are trending higher, M&A activity is showing signs of improving, and net interest margins are poised to expand. Potential deterioration in asset quality remains the dark cloud on the horizon for the banking industry as margin pressures ease alongside weakening economic conditions.

After a tumultuous period for the banking industry marked by bank failures, liquidity concerns, margin pressure, depressed valuations, and subdued M&A activity, the outlook for the remainder of 2024 is cautiously optimistic. EPS estimates are trending higher, M&A activity is showing signs of improving, and net interest margins are poised to expand. Potential deterioration in asset quality remains the dark cloud on the horizon for the banking industry as margin pressures ease alongside weakening economic conditions.

Personal Goodwill and Valuation Issues in Marital Dissolution Cases

What is personal goodwill and why is personal vs. enterprise goodwill such an important topic? How is case law relevant, and is it always relevant? We discuss practical approaches, best practices and the impact from facts and circumstances.

Economic Pressure on Commercial Real Estate Sector

Commercial real estate loans totaled ~$3 trillion across all U.S. commercial banks as of March 2024, which represents a 0.34% increase from February of 2024 and a 3% increase from March of 2023. As seen in the graph below, U.S. banks have continued to expand their CRE loan portfolio over the last ~20 years.

Due to the slowing economy as well as strong preferences for remote and hybrid-working schedules, U.S. commercial property prices decreased by 7% in the past year and 21% since their peak in March of 2022, per Green Street’s Commercial Property Price Index. The increasing number of delinquent loans surrounding commercial properties continues to be a concern for banks, increasing from $11.2 billion in 2022 to $24.3 billion in 2023. Additionally, data from MSCI notes that over $38 billion of U.S. office buildings are pressured by potential defaults and foreclosures, which represents the largest amount since the fourth quarter of 2012.

Six of the largest U.S. banks (JPMorgan Chases, Bank of America, Wells Fargo, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, and Morgan Stanley) have experienced increases in delinquent CRE loans ($9.3 billion in 2023). CRE loans make up ~11% of the average loan portfolio at large U.S. banks, so most large banks have set aside reserves for this sector. Smaller banks, on the other hand, are further exposed as CRE loans account for ~22% of their average loan portfolios.

CRE has long been a hot topic of conversation and CRE regulatory guidance to address elevated concentrations of CRE loans and help institutions manage risk accordingly was released all the way back in 2006. Investors and potential acquirers increasingly focus on CRE concentration levels in assessing valuation and potential riskiness of an institution in today’s environment. For example, an article on S&P Cap IQ noted that investors are increasingly focused on CRE concentrations and those public banks with higher CRE concentrations (those whose CRE loan balances exceeded the 2006 CRE regulatory guidance threshold and had CRE loans above 300% of risk based capital) are experiencing lower returns and pricing multiples relative to their peers in the current environment despite having higher profitability (as measured by ROAA and ROAE and NIMs).

CRE Stress Test – Severely Adverse Scenario

For those banks with a CRE concentration, stress testing can be an important piece of risk management, and the results from the U.S. Federal Reserve’s stress test of the 31 largest U.S. banks in June of 2024 could be of interest. The stress test aimed to assess the exposure levels of large U.S. lenders during a post-pandemic era of record-high vacancy rates in commercial properties (~20%). Balance sheets of these large banks were tested with severe economic scenarios that included the following economic variables : ~36% decrease in U.S. home prices, ~55% decrease in equity prices, a ~40% decline in CRE prices, and a 10% peak unemployment rate.

On June 26, 2024, the Fed released its stress test results examining banks’ ability to continue lending to both businesses and households should a severe global recession occur. The 2024 stress test showed that the 31 largest banks in the U.S. had sufficient capital to absorb ~$685 billion in losses and continue lending to households and business under stressful conditions. These results helped to soothe many qualms surrounding the financial health of the banking industry in relation to CRE loans. While the post-stress CET1 capital ratios remained above required minimum regulatory levels throughout the projection horizon—both in the aggregate and for each bank tested—the aggregate maximum decline in the stressed CET1 capital ratio was 2.8%. This was larger than the decline in 2023 (2.5%) but within the range observed between 2018 and 2022.

For CRE loans, the projected aggregate loan losses under the severely adverse scenario for the three year stressed forecast period (2024-2026) was 8.8% of average loan balances (~2.9% annually). This was above the projected loss rate for the total loan portfolio of 7.1% (~2.4% annually) but comparable to the aggregate loan loss rate for the CRE segment in the 2023 stress test of the largest banks (which was also 8.8%).

Conclusion

It is important when performing a valuation or a stress test of a CRE portfolio to understand that CRE is a diverse asset class that ranges from office to multifamily to retail to hotel/hospitality and industrial/warehouse loans and the potential risk of loss can vary markedly from one type of CRE loan to another. Many factors such as a bank’s underwriting criteria, the property’s type and location, owner and nonowner occupied, guarantor support, historical loan performance, vintage, and occupancy rates can be important. For example, the size of the underlying property alone can impact the expected default rate of an office loan significantly. An article from the Kansas City Fed noted that expected default rates on a sample of office loans in Q4 2023 were ~25% for the largest office properties (those with more than 500,000 square feet) versus under 5% for those with less than 50,000 square feet. Thus, diligence must be taken when performing a valuation or stress test of a bank or its CRE loan portfolio.

Valuing financial institutions and stress testing can be a complex exercise, particularly for those financial institutions with a relatively high proportion of commercial real estate in their loan mix. At Mercer Capital, we have over 40 years of experience in valuing financial institutions through a variety of market and economic cycles. Please call if we can be of assistance in providing valuation or stress testing services to your financial institution.

Supreme Court Upholds Connelly

Life Insurance Proceeds and Redemption Obligations in Buy-Sell Agreements

The United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh Circuit, rendered a decision in the matter of Estate of Blount v Commissioner of Internal Revenue in October 2005.1 The primary takeaway from that decision was that life insurance used as a funding vehicle to pay a company’s liability to repurchase shares upon the death of a shareholder does not add to the value of the company for federal gift and estate tax purposes.

The United States Court of Appeals, Eighth Circuit, rendered a decision in the matter of Thomas Connelly v. United States in June 2023.2 The primary takeaway from that decision is that life insurance received at the death of a shareholder is a corporate asset that adds to the value of the company for federal gift and estate tax purposes.

Given this apparent split in the decisions of the Eighth and Eleventh circuits, the Eighth circuit’s case was offered to the Supreme Court of the United States on writ of certiorari. The Supreme Court of the United States (“SCOTUS”) rendered its decision in the matter of Connelly, as Executor of the Estate of Connelly v. United States (602 U. S. _____(2024), decision rendered June 6, 2024). The unanimous decision of the Supreme Court was rendered by Justice Thomas, who wrote in summary:

Michael and Thomas Connelly owned a building supply corporation. The brothers entered into an agreement to ensure that the company would stay in the family if either brother died. Under that agreement, the corporation could be required to redeem (i.e., purchase) the deceased brother’s shares. To fund the possible share redemption, the corporation obtained life insurance on each brother. After Michael died, a narrow dispute arose over how to value his shares for calculating the estate tax. The central question is whether the corporation’s obligation to redeem Michael’s shares was a liability that decreased the value of those shares. We conclude that it was not and therefore affirm.

I am not a lawyer and am careful when analyzing cases. However, it appears that SCOTUS wrote its decision in a very narrow fashion. It did not, for example, appear to reject the Eleventh Circuit’s decision in Blount, but affirmed the Eighth Circuit’s decision in Connelly.

At the very least, in light of the Supreme Court’s ruling, every buy-sell agreement funded by life insurance should be reviewed by competent legal and tax counsel to ensure that the agreements operate as planned when triggered.

Basic Facts of Connelly

The basic facts can be summarized as follows:

- Michael and Thomas Connelly, brothers, were the owners of Crown C Supply (“Crown” or “the Company”), a company located in St. Louis, Missouri.

- Michael owned 385.9 shares representing 77.18% of the shares outstanding.

- Thomas owned 114.1 shares representing 22.82% of the shares outstanding.

- On August 29, 2001, Michael and Thomas entered into a stock purchase agreement to ensure that Crown would stay in the family if either brother died. The agreed upon value (certificate of value) at that time was $10,000 per share, or $5 million. Under the agreement, the surviving brother had an option to purchase the deceased brother’s shares. If a brother declined to purchase, Crown would be required to purchase the deceased brother’s shares.

- The agreement called for an appraisal process to determine the fair market value of a deceased brother’s shares. Crown was to select an appraiser and the estate of a deceased brother was to select another. Both were to provide fair market value opinions. If the two appraisal conclusions were more than 10% apart, the appraisers would select a third appraiser, who would also provide an opinion of fair market value.

- Crown obtained $3.5 million of life insurance on each brother’s life, which at some point was reduced to $3 million.

- Michael died on October 1, 2013.

- At the time of Michael’s death, there was no agreed upon certificate of value.

- Thomas opted not to purchase Michael’s shares, giving rise to Crown’s obligation to purchase Michael’s shares. The parties did not engage in any appraisal process, as called for in their agreement.

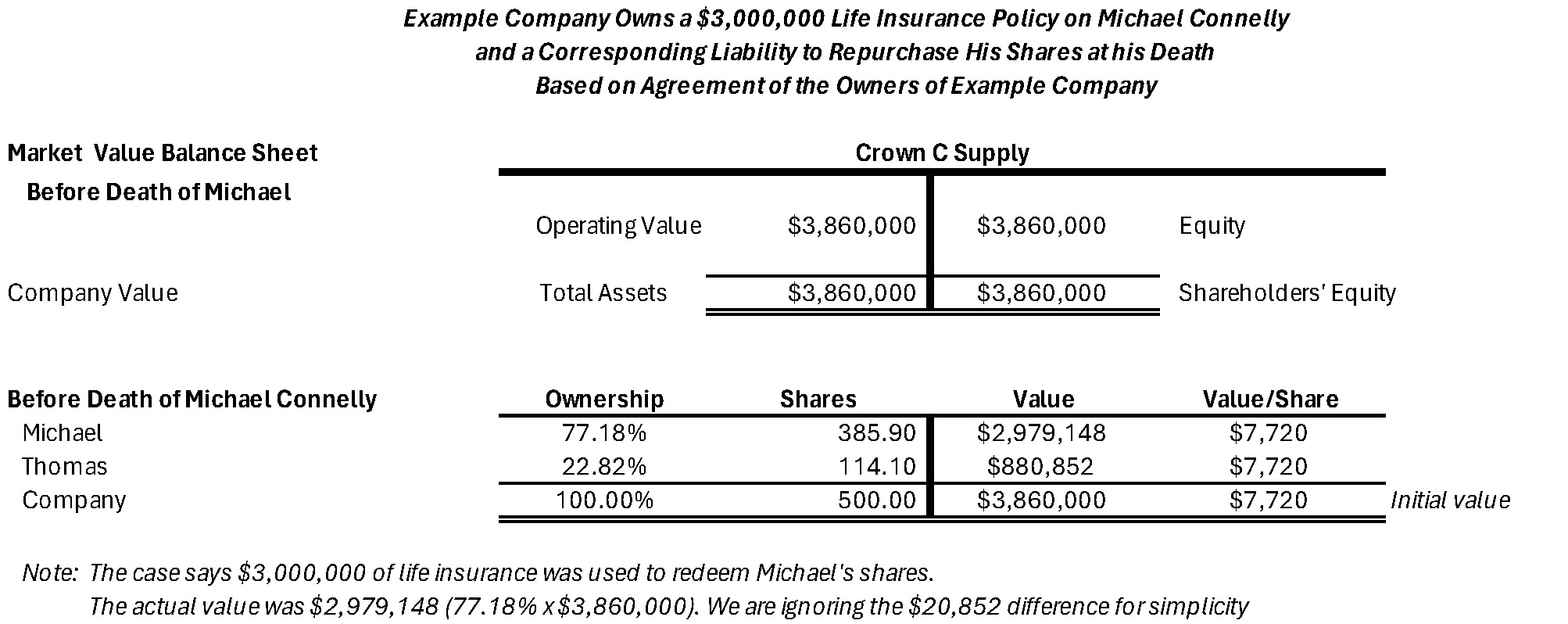

- Michael’s son and Thomas agreed in an “amicable and expeditious manner” that Michael’s shares were worth $3,000,000 (77.18% x $3,860.000 = $2,978,148) of an agreed upon value of $3,860,000). The purchase price resulted from what was described as an extensive analysis of Crown’s books and an extensive analysis of assets and liabilities of the company. Thomas, an experienced businessman extremely knowledgeable about Crown’s finances, was able to ensure an accurate appraisal of the shares.3

- Note the $3 million purchase price for Michael’s shares implied a value for 100% of Crown of $3.86 million ($3,000,000 / 77.18%). Recall that the certificate of value agreed upon in 2001 provided a value of $5,000,000 for Crown, or significantly higher than the agreed upon $3.86 million.

- Crown collected the life insurance proceeds and purchased Michael’s shares for ~$3,000,000, and Michael’s estate filed an estate tax return based on this value.

- The IRS audited the estate’s return and claimed a deficiency of $889,914, or 38.4% of the difference between $5,294,458 (life insurance is a corporate asset) and $2,978,148 (life insurance is a funding vehicle).

- Interestingly, there is no record of an appraisal conducted on behalf of the IRS. During the audit, the Company retained an accounting firm to provide an appraisal. The concluded fair market value, assuming that the obligation to repurchase Michael’s stock was a real liability, was $3.86 million.

- Reading between the lines in the earlier decisions, it seems that the IRS was more interested in challenging the use of life insurance proceeds as a funding vehicle rather than as a corporate asset. The case leaves a big question regarding the actual fair market value of Crown on the date of Michael’s death.

- Michael’s estate paid the deficiency, and Thomas, as executor, sued the United States for a refund.

- The District Court (Eighth Circuit) granted summary judgment to the Government, holding that to accurately value Michael’s shares, the $3 million in life insurance proceeds must be counted in Crown Supply’s valuation.4

- The Eighth Circuit affirmed.

- SCOTUS, in a unanimous decision written by Justice Thomas, affirmed the decision of the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals.

Justice Thomas wrote:

The dispute in this case is narrow. All agree that, when calculating the federal estate tax, the value of a decedent’s shares in a closely held corporation must reflect the corporation’s fair market value. And, all agree that life insurance proceeds payable to a corporation are an asset that increases the corporation’s fair market value. The only question is whether Crown’s contractual obligation to redeem Michael’s shares at fair market value offsets the value of life insurance proceeds committed to funding that redemption.

Whether the SCOTUS decision in Connelly is the death knell of entity repurchase agreements is a question. However, the decision will raise questions and should require every company with company-owned life insurance on the lives of its owners to evaluate the effectiveness of their buy-sell agreements and related life insurance.

SCOTUS Example of a Redemption

Justice Thomas wrote:

An obligation to redeem shares at fair market value does not offset the value of life insurance proceeds set aside for the redemption because a redemption does not affect any shareholder’s economic interest. (at pp. 6-7) (emphasis added)

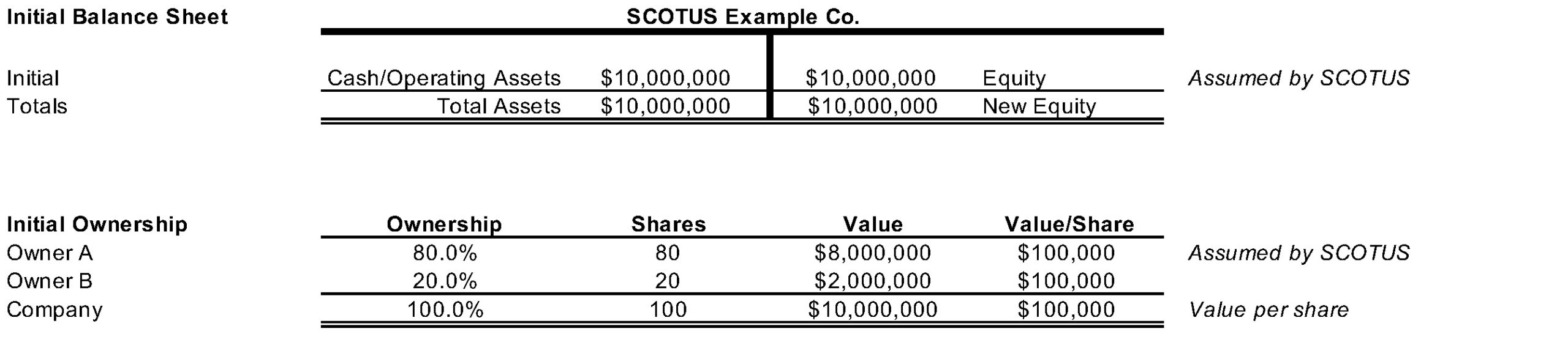

Following this statement, an example is provided in the text of the decision. We examine this example more visually in the analysis that follows. We call the hypothetical company in the decision “SCOTUS Example Co.” The initial balance sheet and ownership of SCOTUS Example Co. are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Click here to expand the image above

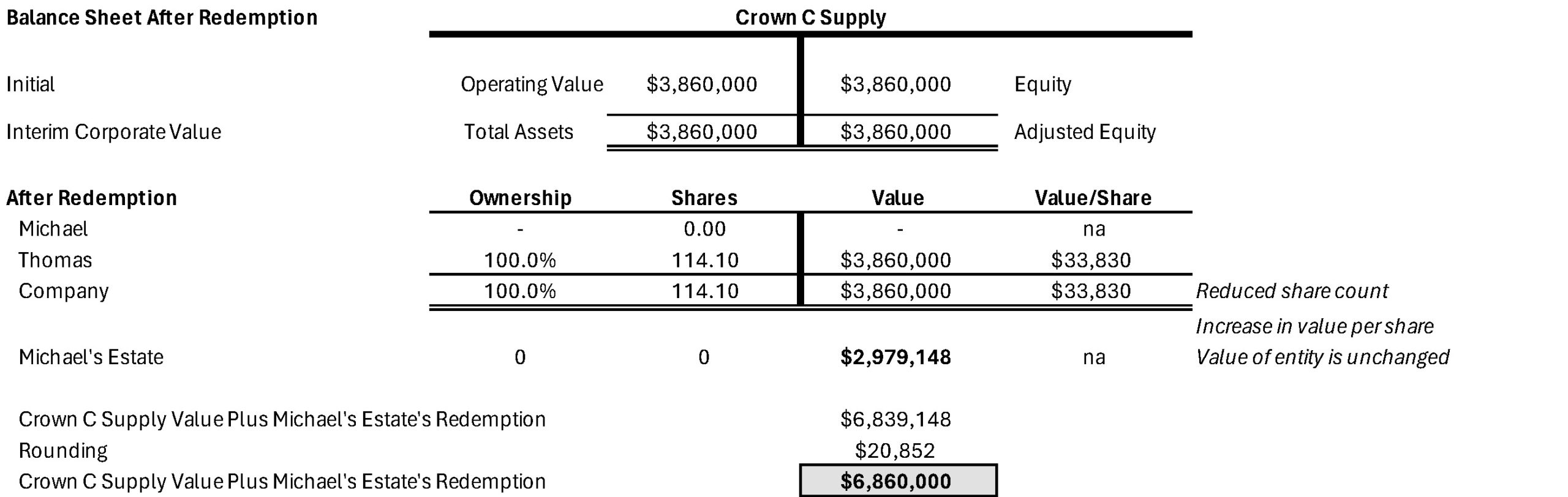

SCOTUS Example Co. has $10,000,000 in cash/operating assets. Owner A holds 80% of the stock which is worth $8,000,000. Owner B owns 20% of the stock, which is worth $2,000,000.

We assume that Owner B dies (and there is no life insurance) or that the Company simply redeems his 20% interest for $2,000,000. The Company retires Owner B’s shares to treasury, and now there are only 80 shares outstanding. The effect of this is to remove Owner B as a shareholder, lower the Company’s value by $2,000,000, and elevate Owner A to ownership of 100% of the shares now outstanding. The remaining $8,000,000 value of the Company plus the $2,000,000 in Owner B’s estate amount to $10,000,000, or exactly the value before the redemption of Owner B’s shares, as seen in Figure 2 .

Justice Thomas then concluded:

The value of the shareholders’ interests after the redemption – A’s 80 shares and B’s $2 million in cash – would be equal to the value of their respective interests in the corporation before the redemption. Thus, a corporation’s contractual obligation to redeem shares at fair market value does not reduce the value of those shares in and of itself.

It is an incorrect conclusion to suggest that the example redemption “does not affect any shareholder’s economic interest.” It is true that Owner B received the $2.0 million value of his shares in the example. Owner A’s interest, while still valued at $8.0 million as before the redemption, now represents a 100% interest in a smaller company. Owner A’s economic interest has, indeed, changed. Instead of owning the right to 80% of the economic benefits of the pre-redemption company, he now owns the rights to 100% of the economic benefits of a company that is different (smaller) than before.

Figure 2

Click here to expand the image above

There is a significant leap from the SCOTUS example to Justice Thomas’s conclusion. There is no life insurance in the example, yet it is the life insurance that is assumed to increase the value of Crown. We examine the case to understand the presumed reduction in value (or not) inferred in this conclusion.

Is Life Insurance a Corporate Asset or Is it a Funding Vehicle?

There are two opposing treatments of life insurance proceeds in valuations for purposes of buy-sell agreements. As I wrote in 2010 in a book about buy-sell agreements:5

Treatment 1 – Proceeds are a funding vehicle and not a corporate asset. One treatment would not consider the life insurance proceeds as a corporate asset for valuation purposes. This treatment would recognize that life insurance was purchased on the lives of shareholders for the specific purpose of funding a buy-sell agreement. Under this treatment, life insurance proceeds, if considered as an asset in valuation, would be offset by the company’s liability to fund the purchase of shares. Logically, under this treatment, the expense of life insurance premiums on a deceased shareholder would be added back to income as a nonrecurring expense.

Treatment 2 – Proceeds are a corporate asset. Another treatment would consider the life insurance proceeds as a corporate asset for valuation purposes. In the valuation, the proceeds would be treated as a nonoperating asset of the company. This asset, together with all other net assets of the business, would be available to fund the purchase of shares of a deceased shareholder. Again, under this treatment, the expense of life insurance premiums on a deceased shareholder would be added back to income as a nonrecurring expense.

The Internal Revenue Service in Connelly treated the life insurance proceeds as a corporate asset to be added to value in the determination of fair market value. This is Treatment 2 above. Michael’s estate argued that the life insurance proceeds should be treated as a funding vehicle to finance the redemption of a shareholder’s shares upon his death, which is Treatment 1 above (and, effectively, the conclusion in Blount).

SCOTUS Treatment of Life Insurance Proceeds

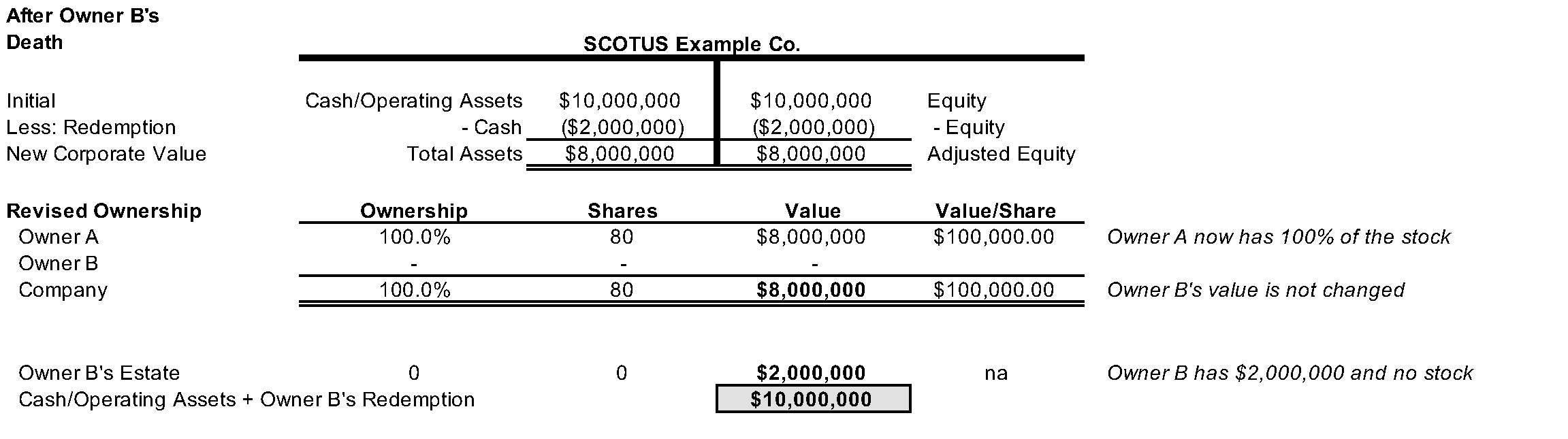

Using the same T-account analysis as with the discussion of SCOTUS Example Co. and a simple redemption, we now look at the effective treatment employed by the Internal Revenue Service and SCOTUS.

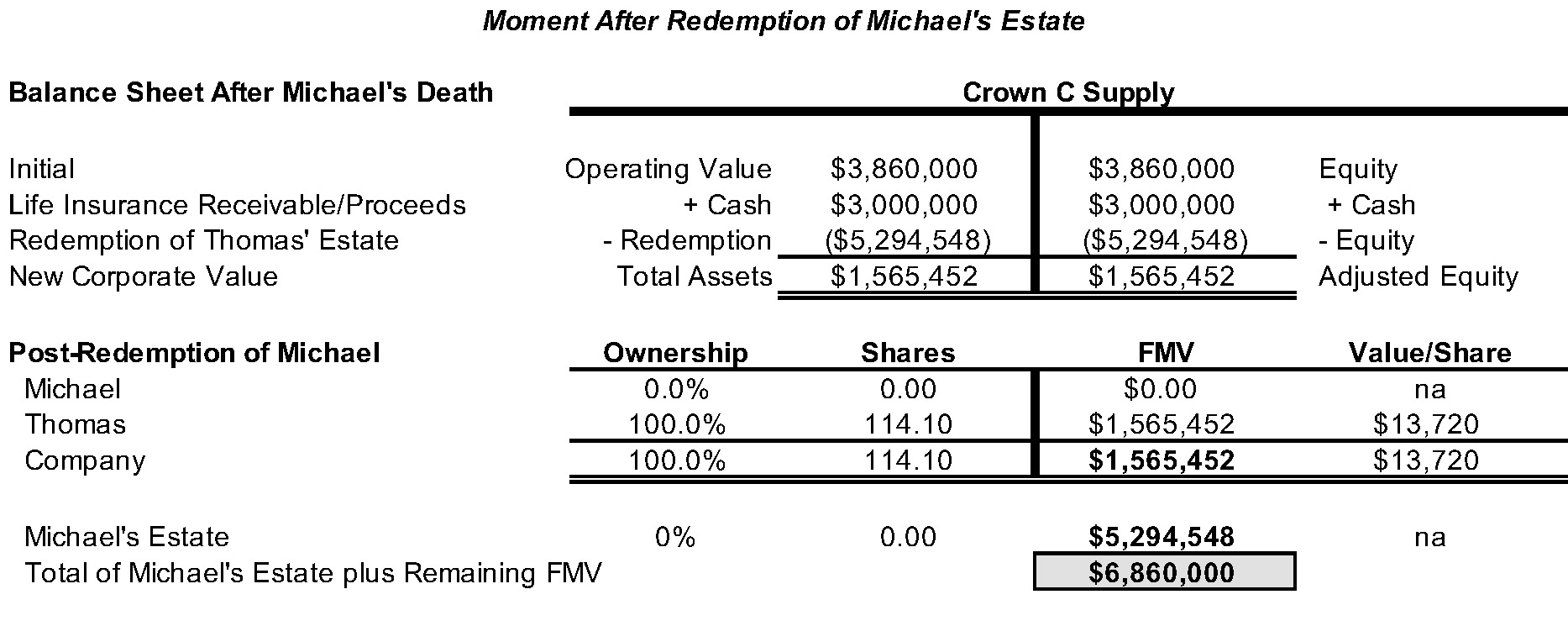

Accept as given that Crown had an operating value of $3.86 million (per the opinion), which is shown in the market value balance sheet at the top of Figure 3. Michael owned 77.18% with a value of $2,979,148 and Thomas owned 22.82% with a value of $880,852. These values represent their respective shares of the $3,860.000 of operating value.

Figure 3

Click here to expand the image above

Now we examine the balance sheet after Michael’s death. The life insurance of $3,000,000 (receivable) is added to the balance sheet as an asset and as equity, raising the total value of the Company to $6.86 million. Michael’s shares were worth $5,294,548 and Thomas’s shares were worth $1,565,452. In both cases, their values per share had risen from $7,720 per share to $13,720 per share, or $6,000 per share ($3,000,000 of life insurance divided by 500 shares outstanding).

In the “Syllabus” released with SCOTUS’s Connelly decision, we see the root of the confusion.6

Thomas’s argument that the redemption obligation was a liability also cannot be reconciled with the basic mechanics of a stock redemption. He argues that Crown was worth $3.86 million before the redemption, and thus, that Michael’s shares were worth approximately $3 million ($3.86 million x 0.7718). But he also argues that Crown was worth $3.86 million after Michael’s shares were redeemed. See Reply Brief 6. Both cannot be right. A corporation that pays out $3 million to redeem shares should be worth less than before the redemption.

Finally, Thomas asserts that affirming the decision below will make succession planning more difficult for closely held corporations. But the result here is simply a consequence of how the Connelly brothers chose to structure their agreement. (Pp. 5-9)

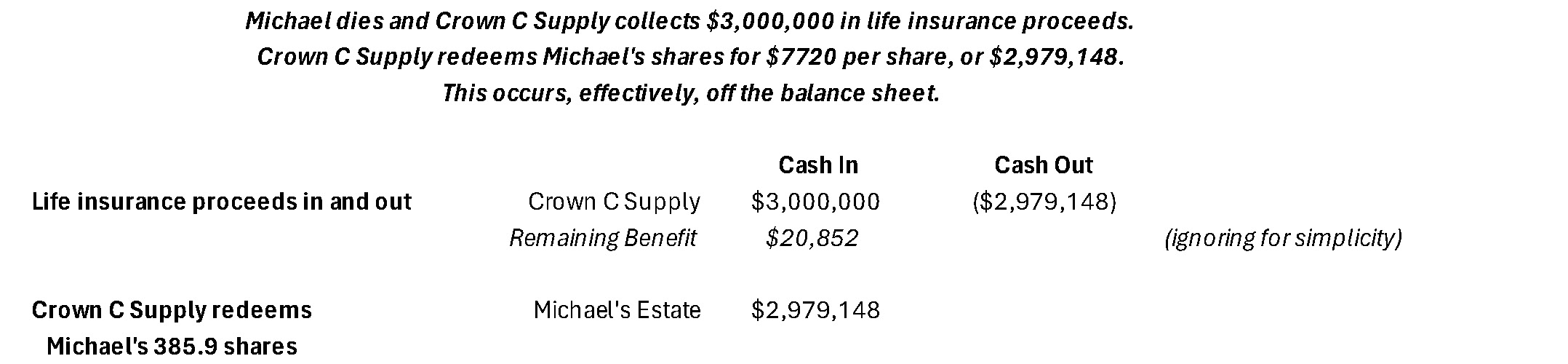

The implicit assumption behind this reasoning is that the value of Crown was $6.86 million before the redemption. However, the fair market value of Crown was $3.86 million before Michael’s death. We finish the example in Figure 4.

The problem is that Crown was not worth $6.86 million until the moment after Michael’s death. However, it was only after his death that the life insurance receivable, which was a contingent asset, available to Crown came into being. And after his death, the contingent liability to redeem his shares was also triggered.

In Figure 4, the redemption, given the new value of $6.86 million, did reduce the value of Crown by $5,298,548, or Michael’s share of that value. Thomas, on the other hand, experienced an increase in value from before Michael’s death ($880,852, or $7,720 per share) to the post-redemption value of $1,565,452, or $13,720 per share. His value increased because he benefited from his 22.82% of the life insurance proceeds (22.82% x $3,000,000) of $684,600. When this is added to his original value of $880,852, his post redemption value is $1,565,452, and his ownership rose from 22.18% to 100% because of the redemption of Michael’s shares.7

Figure 4

Click here to expand the image above

SCOTUS treated the life insurance on Michael’s life as a corporate asset and essentially assumed that this asset was available to the shareholders, while ignoring the contingent liability that Crown had to redeem Michael’s shares.

Presumably, Crown would have to use existing assets of $2.3 million (or borrow funds) to achieve the redemption. This would leave the Company in an undercapitalized state post-redemption with only $1.565 million of capital because the life insurance proceeds were included in the value of the Company. This is precisely the situation that the life insurance proceeds were supposed to have precluded.

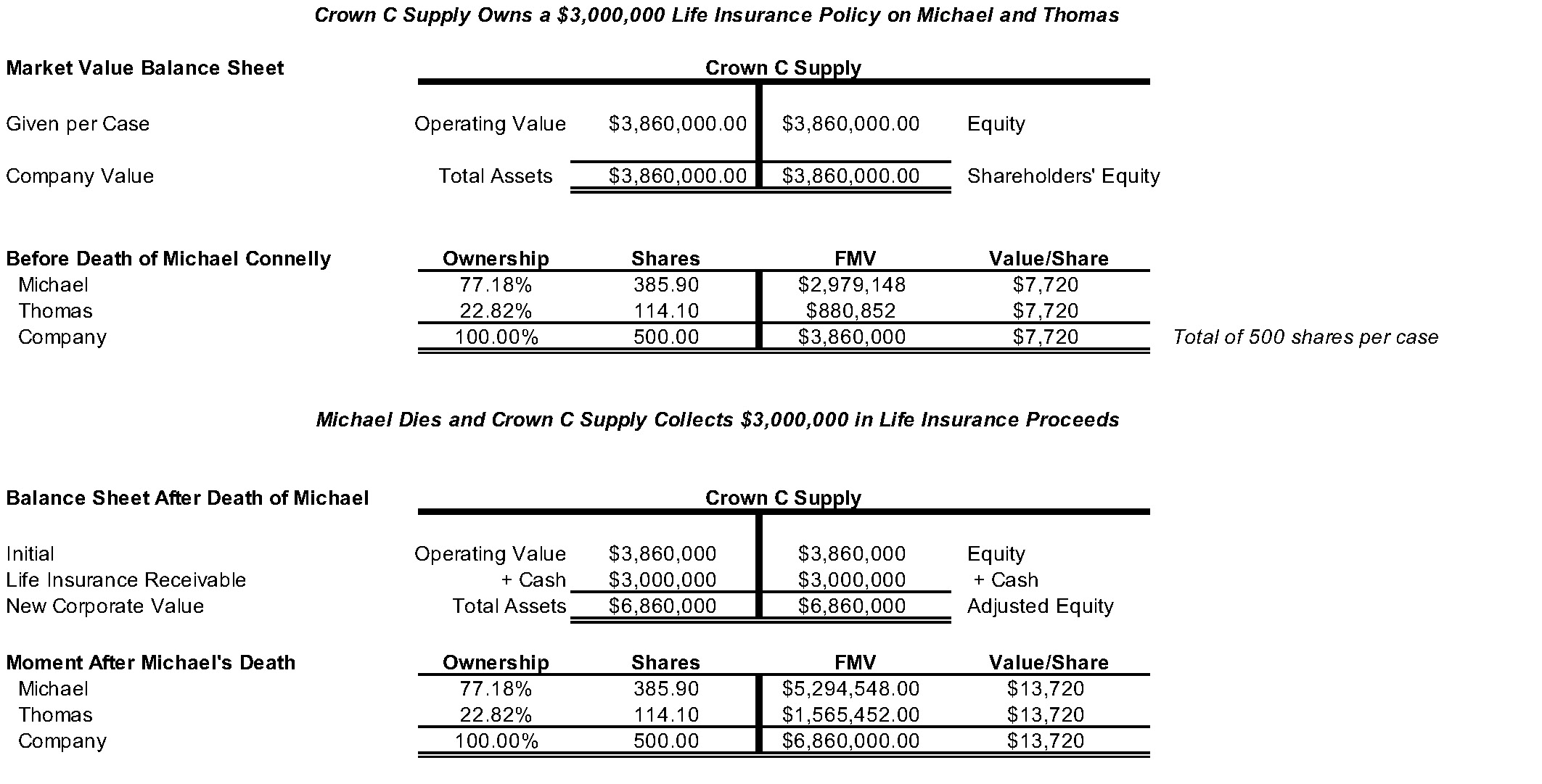

Michael’s Estate Treated Life Insurance as a Funding Vehicle

For clarity, we repeat the initial position of Crown before Michael’s death in Figure 5.

Figure 5

Click here to expand the image above

Crown was stated to have a fair market value of $3.86 million, divided between the shareholders as discussed previously and shown in Figure 5. Upon Michael’s death, the life insurance policy was triggered, and Crown had a receivable and then proceeds of $3.0 million.

Simultaneously, Crown’s contingent liability to redeem Michael’s shares was triggered. What happens, essentially, happens off-balance sheet, as seen in Figure 6.

Figure 6

Click here to expand the image above

At this point, we see that both the contingent asset (life insurance proceeds) and the contingent liability (to purchase Michael’s shares) are used to offset each other. This is how well-written buy-sell agreements have operated for many years. There is most often an appraisal process to determine fair market value, but this was ignored by Michael’s estate and Thomas.

Crown received $3.0 million of proceeds and paid out $3.0 million to satisfy the matching liability.

We now examine the impact of these off-balance sheet transactions on Crown, Michael’s estate, and Thomas, as the remaining owner, in Figure 7.

Figure 7

Click here to expand the image above

Reading the Eighth Circuit’s opinion on Connelly and now the SCOTUS opinion, the judges and justices seemed to think there was some skullduggery on the part of Crown and Michael’s estate. There was not. What the parties were guilty of was not following their own procedures. They did not have a certificate of value to establish the price for Michael’s redemption, as their agreements called for.

Then, when Thomas did not purchase Michael’s shares, the parties did not follow the valuation process called for in their buy-sell agreement. They cobbled together a non-independent valuation.

Had Thomas, Crown, and Michael’s estate followed their own planning, the overall result could have been significantly different.

A part of the quotation above from the “Syllabus” to the SCOTUS opinion is repeated for emphasis.

Thomas’s argument that the redemption obligation was a liability also cannot be reconciled with the basic mechanics of a stock redemption. He argues that Crown was worth $3.86 million before the redemption, and thus, that Michael’s shares were worth approximately $3 million ($3.86 million x 0.7718). But he also argues that Crown was worth $3.86 million after Michael’s shares were redeemed. See Reply Brief 6. Both cannot be right. A corporation that pays out $3 million to redeem shares should be worth less than before the redemption. (bold emphasis added)

As shown here previously, Crown could, in fact, be worth $3.86 million before the redemption of Michael’s shares for $3.0 million and after the redemption, as well. Crown received $3.0 million in life insurance proceeds (the contingent asset) that were used to satisfy the redemption of Michael’s shares (the contingent liability).

There is a similar analysis of the two treatments of life insurance for buy-sell agreements in Buy-Sell Agreements for Closely Held and Family Business Owners.8

Closing Observations

The estate planning world is keenly focused on the SCOTUS decision in Connelly. Does the decision render entity-purchased life insurance useless, or at least, less useful than before? In the short time since the decision was rendered, much has been written and said about the impact of the decision.

Readers of this article will need to examine that literature in the context of future planning for buy-sell agreements and for the reexamination of existing agreements. It is too soon to tell the ultimate impact of this important decision.

ENDNOTES

-

Estate of Blount v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue Service (2005), United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh Circuit, No. 04-15013, October 31, 2005.

-

Connelly, as Executor of the Estate of Connelly v. United States, No. 21-3683 (8th Cir. 2023), decision rendered June 2, 2023.

-

Connelly v. United States, Memorandum and Order, page 21, September 2021. It is clear from all the decisions that no court considered Thomas to be a business appraiser, regardless of his “experience.”

-

Connelly, as Executor of the Estate of Connelly v. United States, No. 21-3683 (8th Cir. 2023), decision rendered June 2, 2023.

-

Mercer, Z. Christopher Mercer, Buy-Sell Agreements for Closely Held and Family Business Owners (Memphis, Peabody Publishing, LLC, 2010)

-

Connelly v. United States, No. 23-146, Syllabus at 2-3 (U.S. June 6, 2024). https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/23pdf/23-146_i42j.pdf.

-

Given the timing of things, Crown turned out better off than the example. Crown received $3.0 million in life insurance proceeds and paid $3.0 million for Michael’s stock. The net worth of the Company after the redemption was $3.86 million. Recall that Michael’s estate paid $0.9 million in estate taxes. It would appear that Michael’s estate received $3.0 million for his shares of Crown. The estate also paid the additional interest demanded by the Internal Revenue Service. That tax was $889,914. The net effect is that Michael’s estate paid taxes on $5,294,548 of value, received $3.0 million for his shares, and had net assets after tax of $2.1 million. The net result is that Crown retained the $2.3 million of extra consideration that the case says it should have paid, leaving the Company with a net worth of $3.86 million ($1.565 million + $2.295 million. The real loser in all this was Michael’s estate.

-

Ibid, Chapter 15.

Personal vs. Enterprise Goodwill: Issues to Consider in Divorce Valuations

This article discusses important concepts of personal vs. enterprise goodwill in valuations for divorce. It is important to understand the business, industry, and efforts of the divorcing spouse(s) & non-divorcing parties to perform a thorough, supportable analysis. It is also important to know how each state treats personal goodwill – some states consider personal goodwill to be a separate asset, and some do not make a specific distinction for it and include it in the marital assets. Additionally, while there are several accepted methodologies for determining % allocations to personal vs. enterprise, there are not uniform standards nor guidelines that govern the how-to’s; as such these analyses are complex and require subject matter expertise.

What Is Goodwill?

Goodwill is the difference between the value of a business less its tangible net assets such as fixed assets. Goodwill is synonymous with intangible assets, and the value of a business is the value of tangible assets + value of intangible assets. Some of the intangible assets can be separated and valued, such as assembled workforce; others fall into the catch-all goodwill category.

What Is Personal Goodwill?

Personal goodwill generally is interpreted as representing attributes that are unique to, and inseparable from, an individual, not able to be transferred. The other portion of goodwill, referred to as enterprise or business goodwill, generally is interpreted as representing value that is owned and/ or that has been created by an enterprise and that can be transferred.

Attributes typically classified within the personal goodwill category include the following:

- Personality

- Reputation

- Personal skill, expertise and knowledge

- Personal relationships

In essence, personal goodwill is represented by certain attributes that are deemed to be incorporated into the very being of an individual, and, therefore, are unable to be sold or transferred to another individual.

What Is Enterprise Goodwill?

Identifiable intangible assets typically classified within the enterprise goodwill category include the following:

- Trademarks and trade names

- Patented and unpatented technology

- Copyrights

- Customer lists and relationships (patient files/records)

- Contracts (employment, noncompete agreements)

- Phone number

- Leasehold

- Trained and assembled workforce

- Location

Why and How Is Personal Goodwill Important?

Many states identify and distinguish between personal goodwill and enterprise goodwill, and further allocate that . This may have a significant impact on the division of the marital estate. However, beyond the business valuation and division, the income derived from the personal goodwill may still be factored into division and/or future support, depending on the state.

Is Personal Goodwill More Common in Professional Services Industries?

Yes – personal goodwill tends to be more prevalent in certain industries than others and varies from matter to matter. The concept of personal goodwill is easier identified and more prevalent in professional service industries such as law practices, accounting firms, and physician practices. Does that mean it doesn’t apply to other industries such as retail, manufacturing, transportation, etc? In order to evaluate the potential carve-out of personal goodwill in an industry/business, the owner/ principal would have to exhibit a unique set of skills that specifically translates to the heightened performance of their business, unable to be transferred to another person/business.

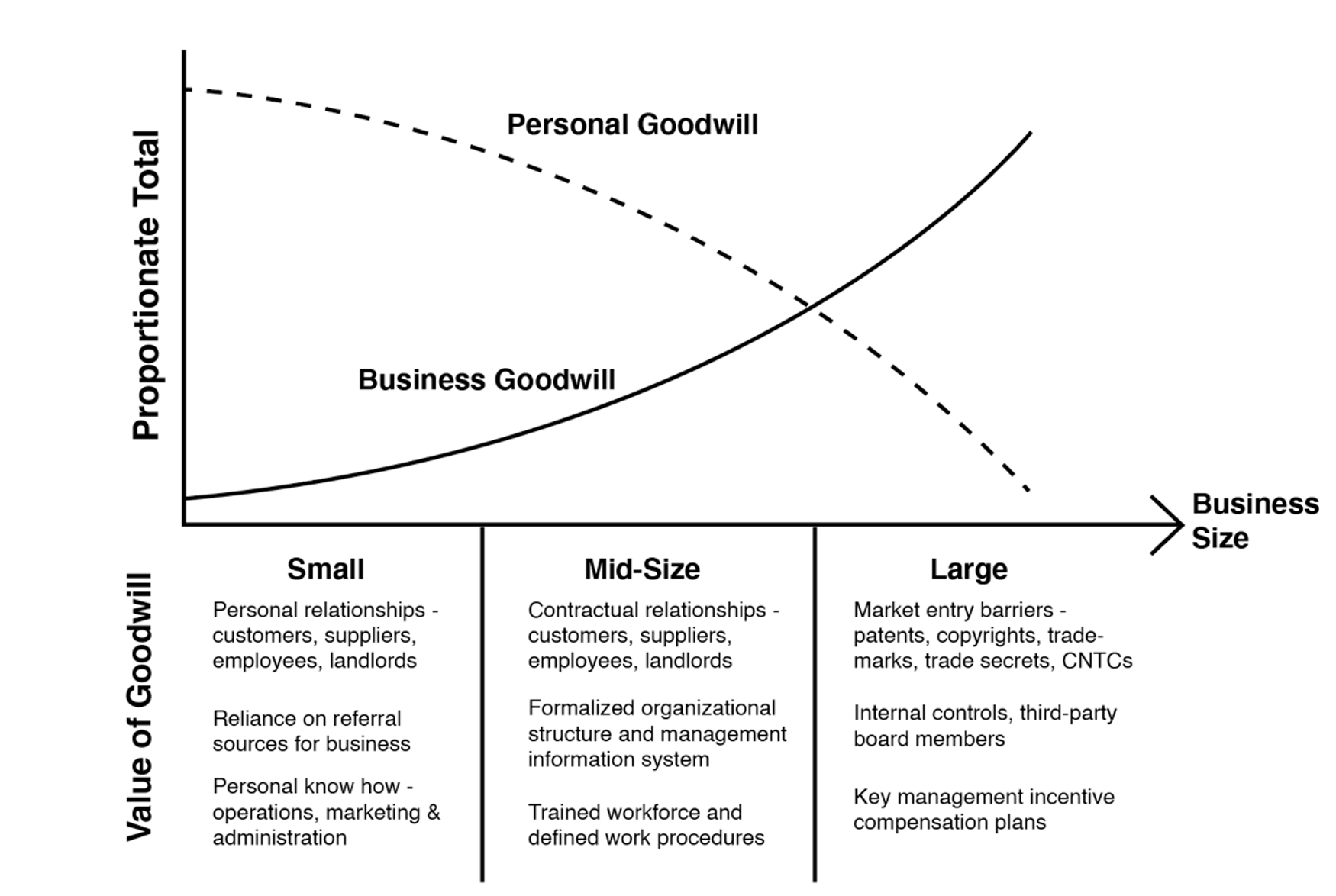

The Goodwill Transition from Personal to Enterprise, Relative to Business Size

The image below illustrates the relationship of changing attributes of business size relative to proportion personal versus business/enterprise goodwill.

Source: BVR’s Guide to Personal v. Enterprise Goodwill

The inverse relationship between business size and percentage allocation makes intuitive sense. One person can only work so much, and their personal impact cannot be scaled like an enterprise, increasing the value attributable to the platform, i.e. the business itself.

Conclusion

There is no one-size-fits-all methodology or approach to allocating personal vs. enterprise goodwill. It will depend on the industry, history of the company, and relative contributions of the divorcing spouse(s) as well as contributions of all other employees, among other factors. From a theoretical perspective, personal goodwill should show the difference in value of the business with and without the contributions from the divorcing party. Personal goodwill has become a common battleground and the need for supportable analyses and subject matter expertise can greatly assist the marital dissolution process. Mercer Capital has extensive experience in this complex topic across various industries and business sizes.

Essential Financial Documents to Gather During Divorce

We have written about the benefits of hiring an expert in family law cases, whether it’s expected to settle or go to trial.

This booklet is designed to be a resource that will assist you and your clients during one of the most difficult times in their lives, both emotionally and financially.

Mercer Capital has compiled a list of financial documents that are typically needed in the divorce process and decoded common financial terms helpful to attorneys and their clients.

Financial experts can assist in determining the relevant documents based on the facts and circumstances of the case, which can reduce the burden of hunting down extraneous documents.

Most financial documents fall into one (or multiple) of the following categories, so we have organized this booklet to address each: